Charlotte high school at center of desegregation sees flip in racial makeup as key players recount experiences

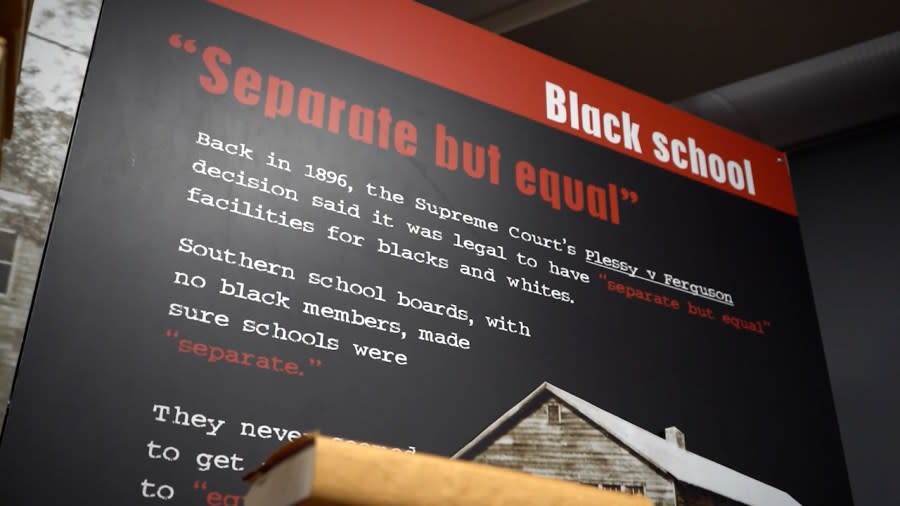

CHARLOTTE, N.C. (QUEEN CITY NEWS) – For more than 100 years schools in America were segregated based on race. In 1954 everything would change with the Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education.

Although they didn’t know it at the time, people in Charlotte would play a major role in what desegregated schooling would look like post-Brown — but it wouldn’t come without a fight.

More than three years after the landmark decision, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools would desegregate. Then-15-year-old Dorothy Counts-Scoggins would become the face of that, as the first black student at the previously all-white Harding High School.

Legacy Lives On: BofA Stadium site served as one of NC’s only Black hospitals during segregation

“It was hard for me to understand it (that) people could treat people that way, the way they treated me,” said Counts-Scoggins.

The photos from that day say 1,000 words. Counts-Scoggins walking with a confident look on her face while a white mob surrounds her shouting racial slurs and throwing things at her. Almost 70 years later, the memory is just as vivid as the day it happened.

“There was an adult who was telling the girls to spit on me,” said Counts-Scoggins. “How can an adult do that to another individual? And all of that was because my skin was different than theirs.”

Her time at Harding was brief as her following school days would bring more hateful comments and even classmates spitting in her food to the point where she had to go home for lunch. But things finally came to a head.

“That was the day that as I was proceeding to leave,” recalls Counts-Scoggins. “I was hit in the back with a blackboard eraser and a sharp object hit the back of my head (while I was) standing in the hallway.”

She walked out of school that day to find her brother waiting in the car with the back window shattered. Someone had thrown something through it. That would prompt her father to call the police that night, and after he was told that they couldn’t guarantee her safety, the decision was made to pull her out of Harding.

“At first it made me feel as if I was a failure,” said Counts-Scoggins.

CMS leaders eliminating vacant positions to avoid laying off employees

The failure wasn’t hers, it was Charlotte’s, as whites in the city fought against desegregation, but they thought she threatened their way of life.

However, the fight wasn’t over. More than a decade later, an up-and-coming civil rights attorney by the name of Julius Chambers, along with his team, would take that fight to court.

“Fortunately, the case was before Judge James McMillan, who himself had no background in desegregation, but was open to listening to the facts of the case,” said James Ferguson, then a young member of Chambers’ team. “In fact, Judge McMillan used to say that he came to this case not expecting to in the order that he did.”

Swann v. Mecklenburg County would build off of the Brown ruling. By law, Brown allowed for schools to be desegregated. The question now was how to bring “meaningful desegregation of schools,” according to Ferguson.

At the time the case went to court, 1,400 Black students attended CMS schools that were at least 99 percent black. Chambers, along with his team, convinced Judge McMillan the way to fix that was busing.

“He recognized that and he entered an order saying that the same mechanism that had been used to preserve segregation would have to be used to bring about desegregation,” Ferguson said.

But just like with Counts-Scoggins at Harding, when a certain way of life was threatened, hateful groups in Charlotte fought back.

“I’ll never forget that morning when I got a call from Vivian Chambers, Chambers’ wife saying, ‘Fergie, we just heard the office was on fire,’” Ferguson recalls.

For Chambers, this was nothing new. His home and car had been bombed before, but now Ferguson had seen it first-hand.

“Sure enough, the office was up in flames and my heart just sunk when I saw that this nice office that Chambers had put together with a contractor here by the name of Malachi Green, and right before my eyes it was burning down,” Ferguson said.

Charlotte City Council passes ordinances to criminalize public urination, sleeping on park benches

Unlike the law office, the Swann ruling would stand, and busing would make Charlotte the model for the South — and in many ways the nation — for meaningful desegregation of schools. However, not all of McMillan’s rulings in Swann were seen through. According to Ferguson, part of it called for schools to be built in areas in between black and white neighborhoods that would have allowed for natural desegregation.

“That never became a reality,” Ferguson said. “There may have been one or two midpoint schools that were actually built in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, but for the most part, we have continued to build schools in racially segregated communities.”

Chambers’ name can still be seen all over Charlotte, from a section of Interstate 85 to the high school on IBM Drive.

Busing would end in 2001, the same way it started: by a court order. Since then, Charlotte’s schools have, for the most part, re-segregated. At Harding, now Harding University High School, where Counts-Scoggins once was the only Black face, now, there’s hardly a white one. Of the 1,234 students enrolled, just 26 identify as white.

It’s a sign that Counts-Scoggins and Ferguson say shows work still needs to be done.

“It’s something we have to do if we’re ever gonna become the nation that we say we are, which is a nation of equality and opportunity for all people,” said Ferguson. “We’re not there yet.”

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to Queen City News.