Charlotte has money to protect trees but neglects urban areas. City vows to do better

For more than a decade, a city program has let developers sidestep Charlotte’s onsite tree-saving rules by paying a fee that city officials can use to conserve land elsewhere.

The payment-in-lieu program, designed to give builders flexibility while protecting the city’s canopy, has helped secure some 260 acres in Charlotte, much of it in perpetuity.

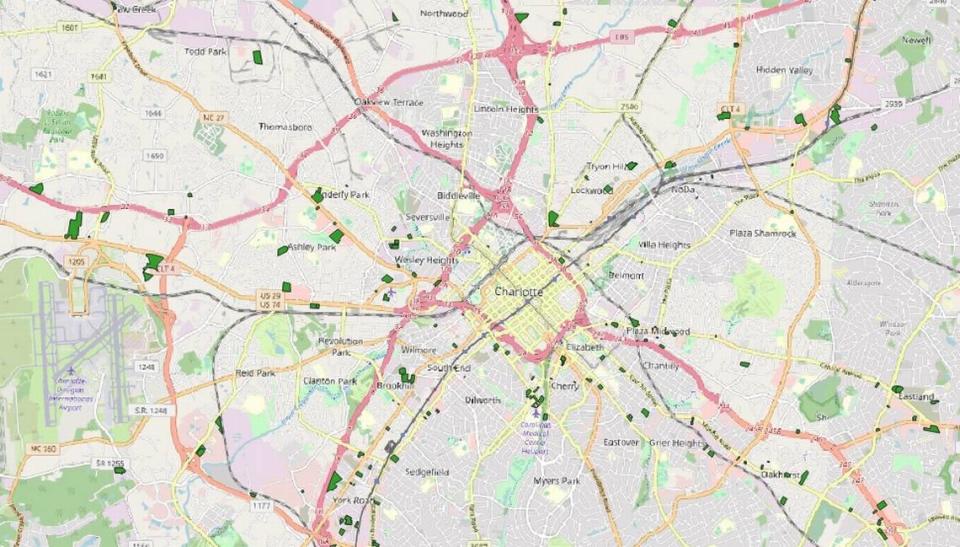

But the program has not preserved the canopy where it is needed the most — in urban areas with few trees and high susceptibility to excessive heat, critics say.

Some of the urban properties the city bought with payment-in-lieu dollars have sat vacant and nearly treeless for years, records show.

Other, larger forested parcels Charlotte purchased are on the city’s perimeters, where there are already plenty of trees, less development and fewer people.

“That’s not what we need right now,” said Doug Shoemaker, ecologist and director of research and outreach at UNC-Charlotte’s Center for Applied GIS. “We need forests, and we need forests where people are. And where there aren’t forests, we need to be planting trees like there is no tomorrow.”

Tree canopy coverage within Charlotte, known as the City of Trees, dropped from 49% in 2012 to 45% in 2018, according to the most recent canopy assessment. Local leaders suspect the newest canopy assessment, due in coming weeks, will show even further declines.

Tim Porter, Charlotte’s chief urban forester, acknowledges that the city needs to acquire more land, particularly in urban neighborhoods.

“The program has not really achieved its full potential or had the highest-level impact that it could,” said Porter, adding that the city gets outbid on about half of the sites that it looks to buy.

Developers pay millions to take down trees

Charlotte’s payment-in-lieu program, also known as the Tree Canopy Preservation Program, began in 2011. It gave developers an alternative to the city’s onsite conservation rules, which now require that a green area covers 15% of commercial, multi-family and residential project sites.

The amount a builder pays to remove trees depends on the land’s zoning, the development site’s acreage and the taxable value of the site. The fee is capped at about $192,600 per acre, as of this year.

Since 2011, owners of some 380 building sites removed more trees than the rules allowed – or didn’t plant enough. The owners deposited more than $12.4 million into the conservation fund, a Charlotte Observer analysis found.

Most of the dollars go to buying properties. Some funds help maintain them or pay staff salaries.

City officials spent $5.4 million of that money, acquiring 22 properties, or about two parcels per year.

They transferred another 21 parcels from other city holdings into the canopy preservation program, which protects land from development, records show. Those properties total 15 acres, or about 6% of all the land the program preserved.

“I’m a little disturbed that so little has been acquired,” said Rick Roti, president of the Charlotte Public Tree Fund, a nonprofit. “Why are we not spending more aggressively? Why are we not planting more trees?”

Most parcels whose owners paid into the fund rather than preserved or planted trees sit along the city’s heavily developed corridors, an Observer data analysis found.

Dozens dot locations along South Tryon Street, North Tryon Street, Central Avenue and Independence Boulevard, where tens of thousands work and live.

But more than 90% of the land conserved with payment-in-lieu fees, sits on the city’s edges, closer to Interstate 485 than uptown, said Shoemaker, who used GIS tools to review the parcels that the city either bought or transferred into its canopy program since 2014.

Porter pointed out that the payment-in-lieu program has protected more acres than the total amount of green areas that would have been preserved if developers had stuck with the rules.

The hiring of Tara Moore as Charlotte’s first tree canopy program manager should help the city pick up purchases, Porter said.

Moore, formerly with the North Carolina Wildlife Federation, started with the city Oct. 2 and will oversee acquisitions and conservation management for lands within the payment-in-lieu program. That includes deciding what properties the city might buy — including those in urban areas — and what to do with some sites that have remained nearly treeless for years.

“We don’t want to plant a tree just for the sake of planting a tree,” Moore said. “We know there is a balance here. We want to come up with an action plan for each site.”

Where are the trees?

Trees, studies have shown, aren’t just pretty to look at. They cool the ground where they stand, a valued trait at this time of climate change. Shaded surfaces can be 20 to 45 degrees cooler than unshaded surfaces, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Trees also help filter particulate pollution in the air and slow the flow of stormwater runoff. Spending time among them can reduce stress and improve mental health, studies have shown.

For people to benefit, trees must be preserved or planted. It’s the planting in Charlotte’s high-density neighborhoods that is slow.

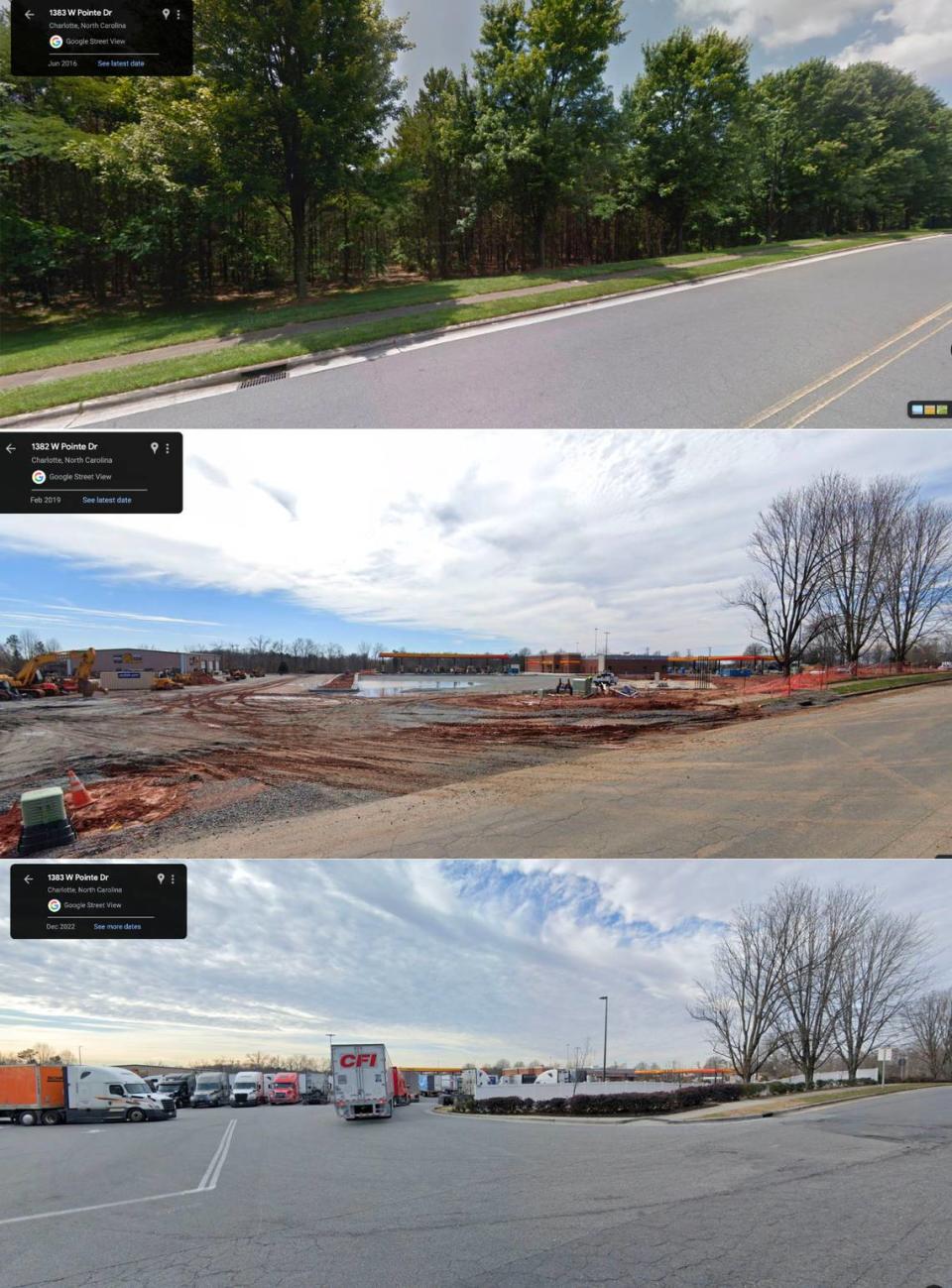

In early 2019, for instance, city leaders used payment-in-lieu fees to buy a single-family neighborhood lot just north of uptown, a block away from Johnson C. Smith University, data show.

More than four years later, the lot, which cost $270,000, is treeless — its grassy field empty save for a blue city sign that reads “Conservation area. Future site of community green space.”

A half-mile away, on Walnut Avenue, sits another empty, nearly treeless lot. The city used canopy preservation dollars to buy that one for $179,000 in 2019, records show.

Just south of uptown near Baxter Street and Queens Road, is another treeless lot sandwiched between two homes. City officials used conservation dollars to buy that property for $320,000 in 2020.

In all, more than a dozen properties that the city bought or transferred into its canopy preservation program have few or no trees, according to payment-in-lieu program records. These are small lots totaling about seven acres, data show.

“I have to ask, is someone asleep at the wheel?” Shoemaker said. “Why aren’t they shading anything they can?”

Reducing heat will become more important for cities as climate change increases the temperature and the intensity of urban heat islands, Shoemaker said. Trees, he said, are the “only climate adaptation response possible for the city at this point,” since adding more air conditioning systems increases the effects of climate change.

City leaders have to start acting preserving and planting trees now, he said.

Urban green spaces

Porter, the city’s chief urban forester, said the complaint about the city failing to plant trees was a “valid criticism.”

“We quickly realized around 2015 that we’re acquiring land, but we are not adding to the canopy,” Porter told the Observer.

He said the city is changing that.

Porter said the goal is to use the small, urban properties in the preservation program to create a network of pocket parks, urban wild areas and gathering places.

How they look will vary, he said. Some will have more trees than others. Some will have more amenities than others.

One of these transformed spots is at the intersection of West 5th and Martin streets. The corner lot held several large, mature trees in 2011, photos show. All were gone in 2019, when the city bought the lot for $130,000.

City officials have since added an assortment of flowers, shrubs, hardscaping and a few young trees.

“A tree-canopy focus is still the primary objective,” said Porter, noting that canopy dollars do not fund everything, such as the additions of decorative rocks. “But we can bring in other features to activate these spaces.”

Hundreds of acres preserved

Miles away from uptown and, in some cases, miles from the development sites that paid to remove trees, are acres of mature canopy that the conservation fund has saved.

For example, the city protected 99 acres of forests between Plott and Robinson Church roads in east Charlotte and 59 acres near Brookshire and Bellhaven boulevards in northwest Charlotte, records show.

The cost of those properties: $2.2 million, data show.

Acquiring wooded parcels is beneficial, said Laurence Wiseman, senior advisor on urban forestry for American Forests.

“Tree protection and canopy growth involves two dimensions,” Wiseman said. “The first is preservation, leaving mature trees in place.”

Porter said the city should finalize two more deals to acquire forested parcels early next year, both costing about $2.2 million, as well.

One would buy 10 wooded acres near Providence Road and Lakeside Drive in south Charlotte — an area that has some of Charlotte’s densest canopy but also some of its biggest losses.

Another would buy 43 acres – 13 acres of forest and 30 acres of hayfields – in east Charlotte near Rocky River Church Road. If the transaction is finalized, the plan is to reforest the agricultural fields, Porter said.

That’s a gain, Shoemaker said.

But Charlotte is “hemorrhaging” canopy, and the city has yet to stop the bleeding where it’s needed the most, he said.

Contractors recently chopped down 22 mature trees in Derita near West Sugar Creek Road to make room for a waterline. The area lost 6% of its canopy between 2012 and 2018, according to Charlotte’s most recent tree canopy measurement.

“The city lacks a sense of urgency of putting trees where they are lost or putting trees where they don’t have them,” Shoemaker said.

“Instead, we’ve taken an easier route and secured land at the edge of the city,” he continued. “You’re taking environmental services away from the city and exporting them to the burbs.”