Charlotte neighborhood experiments with new way to try to thwart gentrification

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Renee Pride-Dunlap returned home to her northwest Charlotte neighborhood in 2008 after two decades away, it felt as though it had been stuck in a time capsule.

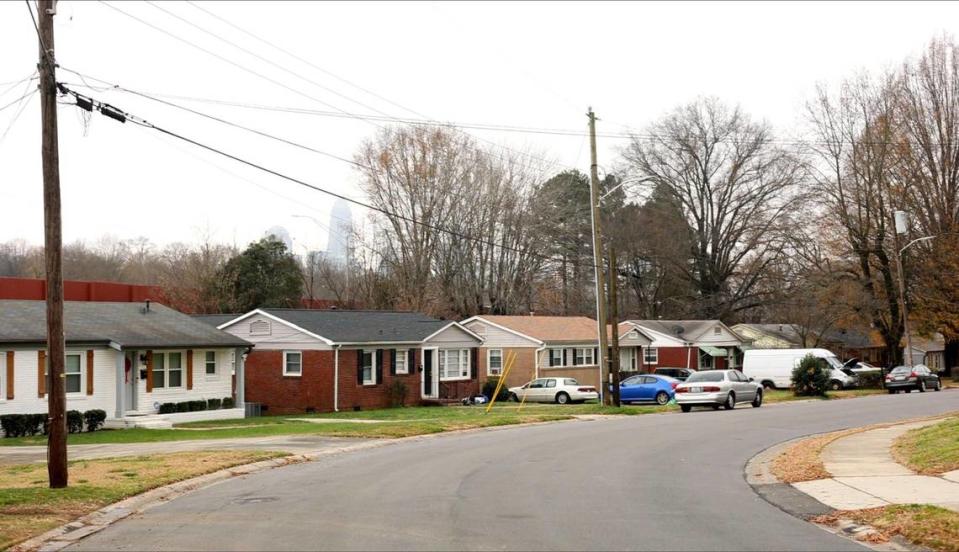

The same modest, brick homes still stood, with many of the same residents still living in them.

But she has watched as nearby neighborhoods experiencing gentrification have lost their character, as developers replace old buildings with “mini-mansions” and modern houses.

“Charlotte has a lot of history,” she said. “But as years go on, they seem to just wipe it out.”

Pride-Dunlap is leading the charge to designate Oaklawn Park, nestled between Beatties Ford Road and Interstate 77, as an historic district. It became the first historic district designated in Charlotte in a decade, after city council unanimously approved the neighborhood’s petition Monday evening.

And it’s the first time that a historic district is in part being explicitly used to fight gentrification in Charlotte. Historic districts recognize areas that are important to the history and character of Charlotte, according to the city’s website.

The neighborhood says the classification will give residents more control over what is built in a fast-changing area through regulating new development and exterior improvements. But some local leaders worry the historic designation could accelerate the very changes that Oaklawn Park hopes to prevent by raising property values faster.

“It’s not the silver bullet that I think some people hope it is,” said city council member Larken Egleston, a former vice chair of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission.

A rich history

Oaklawn Park is one of Charlotte’s best-preserved suburbs built after World War II, according to a report from local historian Tom Hanchett.

It was constructed by developer Charles Ervin between 1955 and 1961 as one of few subdivisions built in Charlotte for Black buyers at a time when deed restrictions barred them from living elsewhere.

Around the same time, Brown v. Board of Education was making its way through the courts. White leaders in South Carolina, where the case began, moved quickly to fund new schools for Black people, hoping they would abandon the idea of integration.

Leaders in Charlotte appeared to have reached similar conclusions, Hanchett wrote. Construction of a new campus for West Charlotte High School began in 1954, and shortly after, developers created Oaklawn Park and neighboring University Park near the school.

Black families who helped shape Charlotte moved into the neighborhood, and some of their descendants remain to this day. They include the Johnson family, which published the Charlotte Post, Dr. Mary T. Harper, who co-founded the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture and Dr. C.W. Williams, a physician who led desegregation efforts in Charlotte medical facilities.

School principals, ministers, postmen, custodians and other professionals and working-class people also purchased houses in Oaklawn Park.

Pride-Dunlap’s father was a doctor and her mother worked as a seamstress.

As she walked through the neighborhood last week, Pride-Dunlap pointed out the neighbors she remembers from her youth who were still there when she returned, from the preacher to her piano teacher.

Those are the people she had in mind when she spearheaded the effort to designate the neighborhood as historic.

“I want to do this to honor them, what they did,” Pride-Dunlap said. “They raised their families here, they took care of the neighborhood.”

Preserving amid change

The neighborhood first found out several years ago that it could be classified as historic when the development of the Interstate 77 toll lanes threatened to overtake a portion of the street Pride-Dunlap lived on, though it would’ve stopped short of her home.

But during that process, a consultant for the state conducted a survey and found that Oaklawn Park was a historic resource, according to a spokeswoman for the North Carolina Department of Transportation.

Then in 2013, the state determined that Oaklawn Park was eligible for the National Register of Historic Places, she said.

That process sparked a conversation among Oaklawn Park residents about whether to pursue an historic designation. The community decided to seek local recognition first, which affords more protections, as investors started to purchase and renovate homes in the neighborhood.

“We were saying, maybe we need to do local first and see if we can get this done before they totally change the neighborhood,” she said.

The district will require new development and exterior changes to existing buildings to be approved by the Historic District Commission, which evaluates projects based on height, materials, setbacks and other features.

And anyone demolishing a structure will need permission from the commission first, though tear-downs can only be delayed, not stopped.

“Basically our hopes are that this will be a neighborhood that people will seek out,” Pride-Dunlap said. “Because if we’re historic, we feel like we’ll get the people in that really care about their property.”

A gentrification tool?

Pride-Dunlap said the goal is to maintain the historic character of Oaklawn Park. But she’s also hoping that residents will be able to afford to stay in their homes.

A 2016 study of New York historic districts found that socioeconomic status, the share of college-educated residents and the mean household income all rise after designation, relative to nearby neighborhoods that are not historic. But the research found that rents do not rise, and racial composition does not change, in comparison to those other areas.

Brian McCabe, an associate professor of sociology at Georgetown University and co-author of the paper, said maintaining the buildings in an area doesn’t mean that the same people will be able to stay there.

“I do think historic preservation is going to freeze in some capacity the physical infrastructure that’s there,” he said. “If the goal is to preserve the social character, I’m not sure preservation is the right tool for that.”

Housing costs have risen rapidly in Charlotte’s historic districts, which include Dilworth, Plaza Midwood and Wesley Heights.

Hanchett, who lives in Plaza Midwood, said real estate in older neighborhoods is becoming more valuable. But he said historic districts are one small tool that can give residents a voice in the changes that occur.

“The things that give existing neighbors a say in the change in the neighborhood are empowering and can help folks grapple with the pressure of development,” he said.