Charlotte’s Polk Park demolished without public input. Now, community wants answers.

It’s called a “pocket park” due to its small size — but the impact left after tearing down Polk Park will be big, historical preservation organizations say.

Earlier this year, there was a $5 million fundraising plan to renovate the existing uptown park and retain its historic elements. Instead city officials chose to demolish the beloved park on Wednesday, without holding public engagement as to what would replace it.

In March, city officials inked a deal with nonprofit Charlotte Center City Partners and shifted gears. The plan now calls for rebuilding the smaller-than-an acre park and naming it for Hugh McColl, Jr., Bank of America’s former chairman and CEO.

It’s a move that has rankled preservationists and advocates. They say it’s an example of erasing the city’s history.

“This is sort of shocking that this could happen in 2023 in a city that is celebrated as so forward looking, that we could in fact, be returning to an era of just destroying like we saw during urban renewal,” Cultural Landscape Foundation President Charles Birnbaum said.

But city officials counter that the park was dangerous, citing the park’s sharp edged design and fountain. It’s not compatible with nearby properties and doesn’t have a lot of room for activity, city spokesman Lawrence Corley III said.

“The choice to remove the fountain designed by Angela Danadjieva, a respected landscape architect, was weighed heavily,” Corley said in an email. “The cost to rehab the park was too significant and given the challenges previous stated, City Council voted to redevelop it.”

LaWana Mayfield, the one city council member who voted against the demolition, said what got them to this point was the city’s failure to maintain the park. She told the Charlotte Observer Thursday that before the council vote, she assumed the park was maintained by Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation.

Many questions, no public input before demolition

The agreement with Charlotte Center City Partners approved by the city council in March lists multiple opportunities for public engagement.

“Significant public engagement is planned to ensure all stakeholders are informed of the city’s intent to redevelop the park,” the March 13 city council agenda says. “The city and Charlotte Center City Partners will partner in providing special care to the families of those honored at the current park.”

It never happened nor was it required because of the scope and type of project, Mayfield said, but she doesn’t agree.

“I always believe the community is able to have an opportunity to speak especially when we’re looking at something that’s a landmark,” Mayfield said. “Anytime there’s a transition the community needs to be a part of this decision.”

Charlotte Center City Partners refused comment when contacted by the Observer Thursday.

Sarah Sue Hardinger, president of the Mecklenburg Historical Association, said Charlotte has a history of handing over noteworthy sites to developers in deals without acknowledging their significance.

Birnbaum questioned why the city had a sense of urgency to demolish the park just two months after the council’s approval, but lacked the same urgency for maintenance of the park.

“What is tragic here is the loss of such a significant work of art with without any public engagement,” Birnbaum said.

The city committed $350,000 to the demolition project.

“As a practical matter, deconstruction/demolition estimates were approximately the same value, so the City committed to manage the deconstruction,” Corley said.

Mecklenburg Historical Association says it was left out

Corley said the city and Charlotte Center City Partners have been engaged with the Mecklenburg Historical Association— but Hardinger doesn’t feel like she’s been a part of the process.

The association sent letters to the city and Hugh McColl, Hardinger said.

“We thought that having a park that was talking about the founding of the county at the point of the founding of the county was very appropriate,” Hardinger said

Hardinger said she never received a substantial response.

“There was a fairly standard note from the mayor’s office denying us conversation with the mayor and suggesting we could talk at the council at some point long after the vote had been taken,” Hardinger said.

The park’s lost history

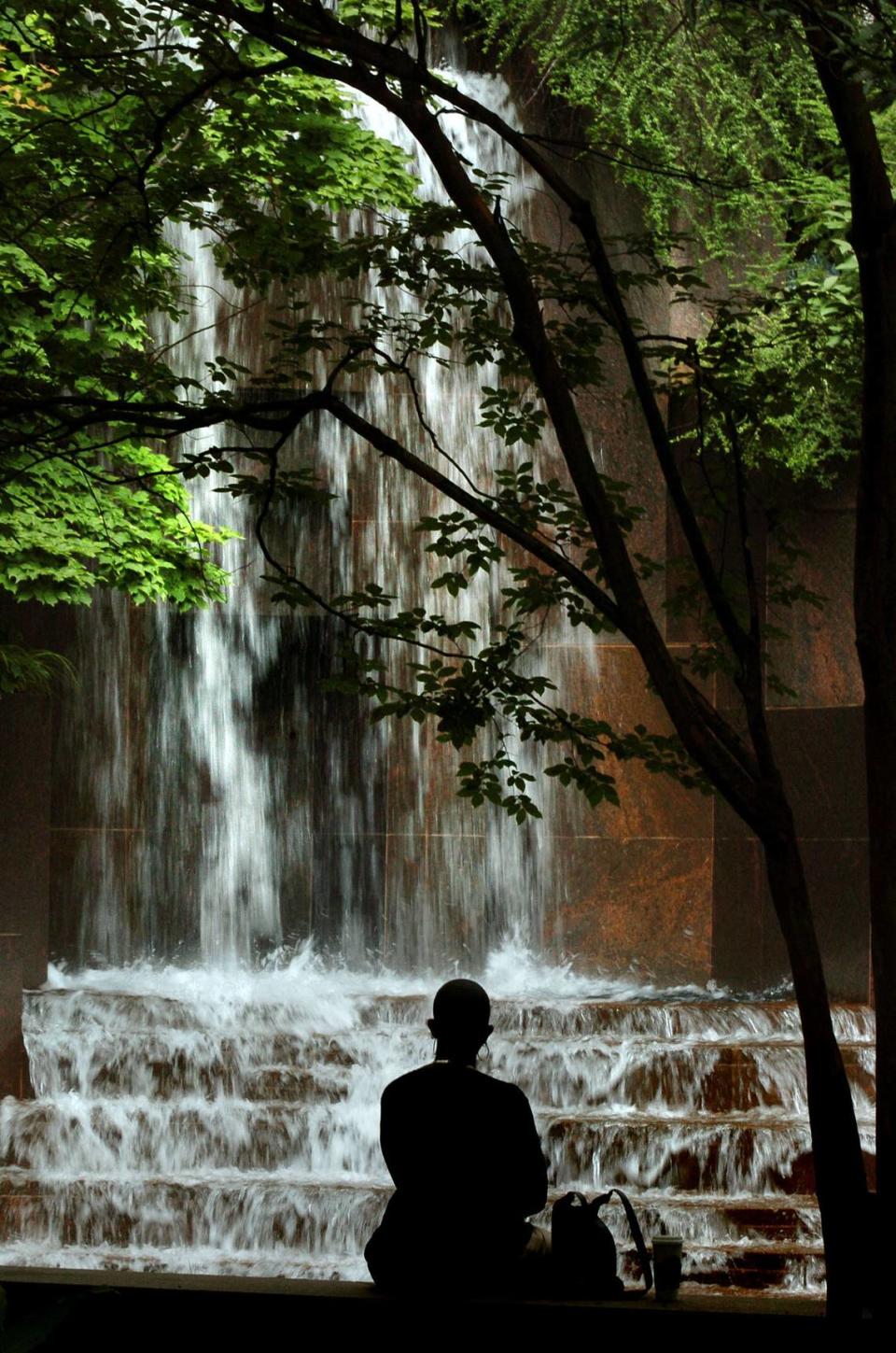

Before it was the pile of rubble that sits on the site now, cascading waterfalls once flowed down a giant stone staircase.

Built in 1991, the park is more than three decades old. Its fountain structure and the systems have exceeded their useful life, city officials said in an email.

However, the site was the only known city park designed by a female architect.

“Is there another significant work of architecture, art or landscape architecture in Charlotte, that young women could see as something in the built environment that says, ‘You know what? I want to work in cities. I want to shape cities. I want to create art when I grow up,” Birnbaum said.

The park is also the site of where commerce began in Charlotte, at the corner of Trade and Tryon streets.

“Thomas Polk was a huge mover and shaker,” Hardinger said. “Honoring him was good and having it at that point where the place was founded was very important.”

Two plaques about Polk are being preserved from the park and moved to his grave site, Hardinger said.

Mayfield is wary of naming things after people who are still alive and said there are other community members whose work goes unnoticed that the park could be renamed for instead of McColl.

What we know about the future of the park

We don’t know much about the future of the park, but we know who will head the decision making.

Center City Partners formed the Hugh McColl Park Coalition that is currently fundraising for a “functional, flexible, and elegantly crafted urban park that celebrates Charlotte’s history. The design will acknowledges McColl’s vision and contributions as a

In the Charlotte Business Journal, McColl said he isn’t involved with the project besides agreeing to let his name be used.

The coalition includes:

▪ Malcomb Coley, Charlotte managing partner for Ernst & Young

▪ Cyndee Patterson, former city councilwoman

▪ Kieth Cockrell, president of Bank of America Charlotte

▪ Harvey Gantt, former Charlotte mayor

▪ Michael Marsicano, former president and CEO of Foundation For The Carolinas

▪ Loy McKeithen, former partner at McGuireWoods

▪ Rolfe Neill, former publisher of The Charlotte Observer

▪ Michael Smith, president and CEO of Charlotte Center City Partners.

Why did Polk Park get demolished?

Ten members of the Charlotte City Council agreed in March it was time for Polk Park to be razed and renovated. The park was frequented by rats, Mayor Pro Tem Braxton Winston said.

But much of how the decision changed from renovation to demolition remains unknown.

Preliminary designs from 2016 for renovations would have cost $4 million to $5 million, Corley said via email.

But there was no funding source for the renovations, so the city looked to the Republican National Convention, which was coming to Charlotte in 2020 and expected to bring in revenue. The convention was significantly downsized due to COVID-19.

“A survey was also done in 2019 when we were rushing to get the project done for the RNC. Research and engagement were paused after 2020 when the RNC was scheduled,” Corley said. “The tasks underway were completed but no additional work was done given the funding situation.”

Construction costs began to increase and no funding was dedicated to the project.

During COVID, the park was no longer a city priority, Corley said. When things began to return to business as usual, a private sector group approached the city about a public-private partnership to renovate the park.

It’s unclear when this happened.

“The terms of the agreement were that the private group would lead fundraising for the design and construction and the group engaged Center City Partners to lead public engagement,” Corley said.