How a Charlotte writer learned to make poetry by blacking out parts of the Bible

Caeli Faisst was an undergraduate at SUNY Fredonia in the 2010s when her fiction professor posed a question to the class: Do you hold books sacred?

Of course, they said, although they didn’t offer a lot of clear responses for why.

What happened next was a pivotal moment for Faisst, a 29-year-old Charlotte writer and artist. Thanks to a new grant providing studio space at the Visual and Performing Arts Center, she’s experimenting with a type of poetry that saw its roots in that long-ago class.

The professor held up a book and proceeded to tear it, first the binding then the cover then the pages within.

“I remember sitting with that and thinking, what is it that I hold in my space that I hold sacred?” Faisst said. “And why do I hold it sacred? And if I chose to do something that was considered not sacred to it, what would that change in me? As someone who grew up Christian, my first thought was that I hold the Bible sacred.”

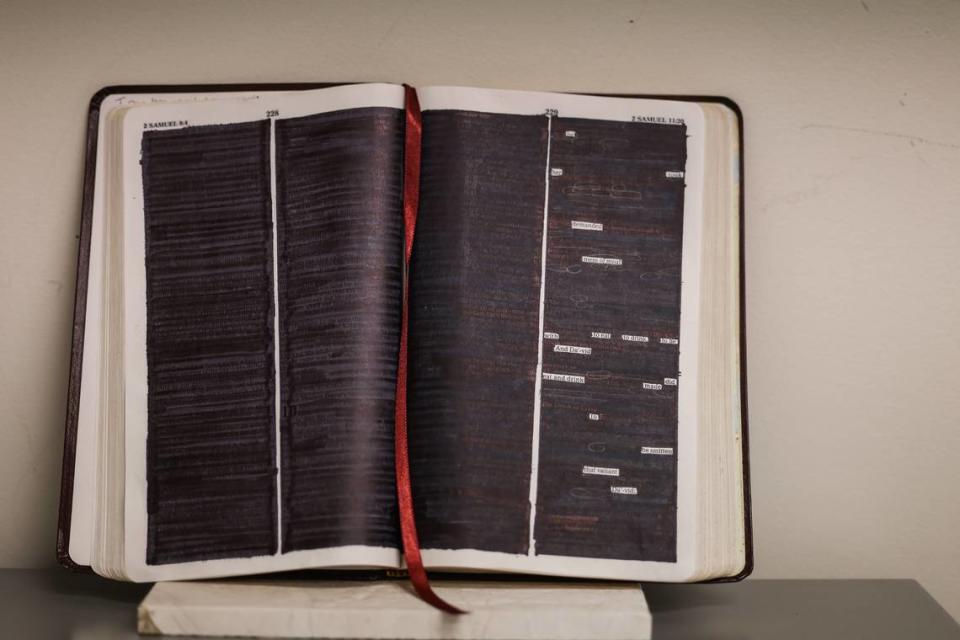

That thinking formed the basis of her current creative project, an exploration of sacred religious texts through a medium called blackout poetry.

What is blackout poetry?

Unlike epic, sonnet or haiku poetry, blackout poetry subtracts words instead of adding them.

A writer identifies a text of interest then blacks out words on the page. What remains tells a story in what is also sometimes called erasure poetry.

Though Faisst learned about blackout poetry during college, she was slow to embrace it, feeling conflicted for reasons that had nothing to do with poetry.

“I remember thinking what would happen if I just blacked out the Bible? And it terrified me, this idea of taking something that my faith was based in and just in my head ruining it,” Faisst said. “But I couldn’t get the idea out of my head.”

New inspiration from an old Bible

Like a number of others creating blackout poetry, Faist takes a document and identifying who has been excluded or erased from the content. Then she restructures it to tell the story of the person left out of the original narrative.

While walking around Charlotte last year, Faisst found a book that wound up as the pillar of her current project — an old Bible left in one of the Little Free Libraries around town.

While thumbing through it, she saw it had been a gift that someone had received for their wedding because there was an inscription in it wishing the recipient a happy marriage.

The Bible also contained little notes that the person had written to themselves. Faisst felt sad, wondering what led to the owner giving away a Bible that they received for their wedding.

The inscription had been written to a woman. As Faisst continued looking through the Bible, one passage, Proverbs 31 — which provides advice for virtuous women — caught her attention. It was highlighted with the person’s notes.

“When I brought it home, I took a marker and I just started blacking out everything, except for certain words that she had scribbled under. It was oddly freeing,” Faisst said. “And then I just kept doing it.”

‘The virtuous woman’

One example of Faisst’s blackout poetry project came from reworking Proverbs 31, focusing on verses 10-29, to read:

The virtuous woman

her price is

her hands

fruit

her merchandise

Her husband

her mouth

Finding fellow creative types

After the New York native moved to Charlotte six years ago, she wanted to make connections with other artists and creatives.

Faisst credited Charlotte Is Creative for holding inclusive events that provided the opportunity to meet like-minded peers. “Those were the best places for me to meet people because everyone just showed up regardless of what creative medium they worked in.”

Her work has been featured around Charlotte at shows such as last month’s Doomsday and Night art exhibition at Camp North End as well as exhibitions produced by Goodyear Arts.

A Charlotte is Creative grant she received this year provides her with studio space at the Visual and Performing Arts Center. The program is a partnership with Nine-Eighteen-Nine Studio Gallery in VAPA to provide studios and access to creative peers.

For her blackout poetry, fellow creatives encouraged her to take the project seriously, including Boris “Bluz” Rogers, one of the progenitors of the local poetry scene. Rogers connected her with Goodyear Arts, where Faisst put her efforts into creating work that pushed back at patriarchal authority and hegemony in religious texts.

Faisst’s project for the most recent Doomsday Arts show, where she presented two pieces, was the debut of this exploration. One was a blackout poem of the first page of Genesis and the first page of Revelation.

Her second piece was on the story of Bathsheba, which she explored through a feminist lens.

“The story of Bathsheba is always told as though Bathsheba and King David commit adultery together. But... Bathsheba doesn’t really have a lot to do with what happened,” Faisst said. “In one of the verses it specifically says, David saw her, told his servants about her and then it says his servants took her and she came to him.”

This realization prompted Faisst to keep doing research and reading through different translations. Her findings became the first part of a longer piece she is now working on, which goes through stories of either overlooked or misunderstood women throughout the Bible.

Tim Miner, co-founder of Charlotte Is Creative, said Faisst’s application for the grant program stood out because of the creative and intellectual rigor of her project. Her expression of need for a room of her own to work on her art, while balancing a day job as a content writer, also was compelling.

Faisst is grateful for the creative friends and connections she has made throughout the Queen City.

That includes the chance encounter with the donated Bible that has bloomed into her current work. “Story of my life,” she said. “I have found that doing things on a whim usually leads me to unexpected places that I love.”

More arts coverage

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up here for our free “Inside Charlotte Arts” newsletter: charlotteobserver.com/newsletters. And you can join our Facebook group, “Inside Charlotte Arts,” by going here: facebook.com/groups/insidecharlottearts.