The Fourth of July lesson you didn’t know you needed

For a brief moment in time we’re all captivated by chemistry.

A whizzing sound shoots straight into the sky. A crack reverberates. And electric colors burst into a black night sky, fizzling into apparent nothingness. It’s a process that many of us fireworks-lovers, stretched out on blankets and awing at the sight, likely know little about.

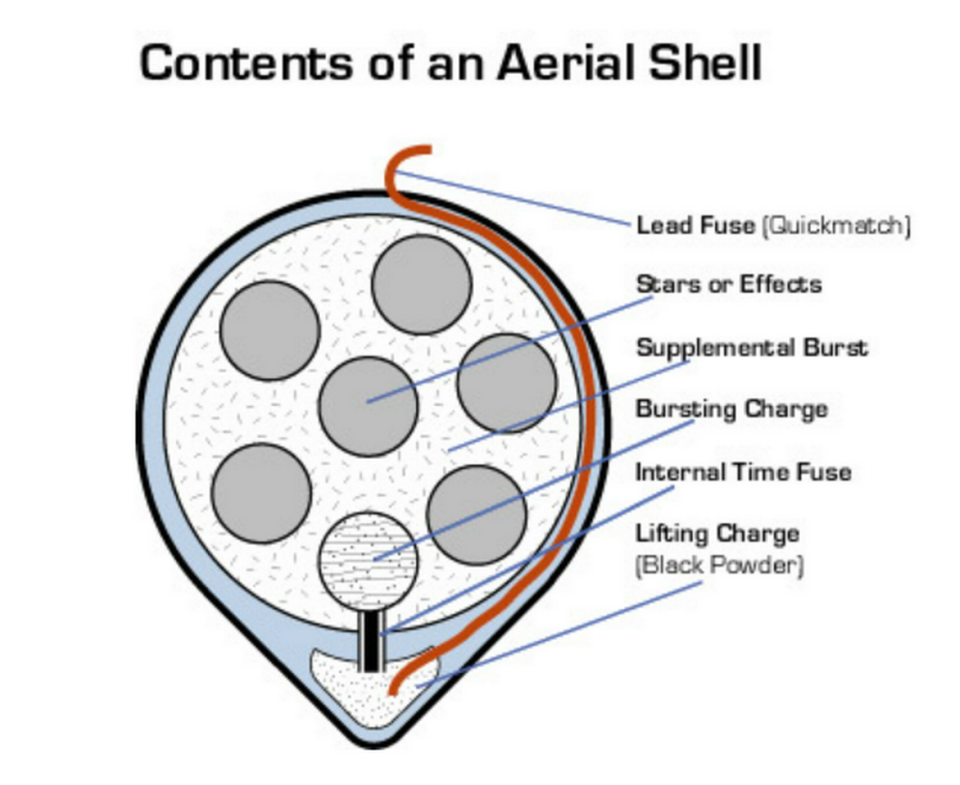

Inside fireworks is a tube called an aerial shell, which contains all the explosive chemicals, according to the American Chemical Society. That’s right. All the lights, colors and sound emitted come from that small tube.

The aerial shell is mostly made of gunpowder — typically potassium nitrate, carbon and sulfur — and small bits of explosive materials known as stars, which give fireworks their color once they erupt. Really, when we’re gazing at fireworks, we’re watching the explosion of these stars, chemists say.

Now, what gives fireworks their color? The U.S. Geological Survey points to minerals.

Red: Strontium. Outside of fireworks it’s used in signaling, oil and gas production.

Green: Barium. It’s used in medicine, oil and gas production.

Yellow: Sodium. Used in the production of polyvinyl chloride plastic.

Blue: Copper. One of the oldest metals humans benefit from, it’s used in electronics and power generation.

Gold: Iron filings and small charcoal pieces.

Orange: Strontium and sodium.

Lavender: Copper and strontium.

Silvery white: Titanium, used in white pigments and metal alloys. Zirconium, used for high-temperature ceramics. And magnesium, used in furnace linings and manufacturing steel and ceramics.

Happy #4thofJuly! As you safely and responsibly enjoy the #fireworks today, check out the #minerals that give them their gorgeous colors. #DYK that those minerals have other uses in our lives? Some of them are even #criticalminerals: https://t.co/yUFqbAWfSb pic.twitter.com/ImRJpPFW5Q

— USGS (@USGS) July 4, 2022

Ready to launch

Each star contains an oxidizing agent, a fuel, a metal-containing colorant and a binder. Once fire sparks the oxidizing agent and fuel, they chemically react creating heat and gas, the American Chemical Society said.

The metal-containing colorant makes the color and the binder secures together the oxidizing agent, fuel and colorants. At the core of the shell is a bursting charge with a fuse. Once lit, the bursting charge and aerial shell are triggered to explode.

This is the part some who have launched fireworks know well.

The shell is put inside a mortar, below the shell is a lifting charge of gunpowder with an attached fast-burning fuse. When lit, the gunpowder explodes, creates heat and gas and builds up pressure under the shell causing it to blast into the sky.

Another fuse inside the aerial shell — a time-delay fuse — ignites and sets off the bursting charge. Then the black powder and stars are triggered, which causes the rapid production of gas and heat sending the stars everywhere.

It’s the stars, those small bits inside the aerial shell, that matter when it comes to what shape will appear in the sky. If the stars are randomly arranged, they’ll spread evenly once they burst. But if they’re packed in a pattern, such as the well-known willow, they’ll fall accordingly.

What about the sound?

Aluminum powder is to blame for your dogs sheltering in place when the crack of a fireworks explosion sounds, the U.S. Geological Survey says. And the American Chemical Society confirms that the boom is indeed the great sonic boom, which occurs because the gases expand faster than the speed of sound.

But if the fast-acting and time-delay fuses don’t sync, the shell may never lift off. The once chemically compact and controlled explosive becomes, well, a loose cannon.