Chicago to Detroit Freedom Trail honoring enslaved freedom seekers would stop in South Bend

SOUTH BEND ― After retiring from a three-decade tenure at a university, Larry McLellan spent years gathering the stories of thousands of enslaved African Americans who, from the 1830s up to the Civil War, passed through the Chicagoland area on their way to freedom in Canada.

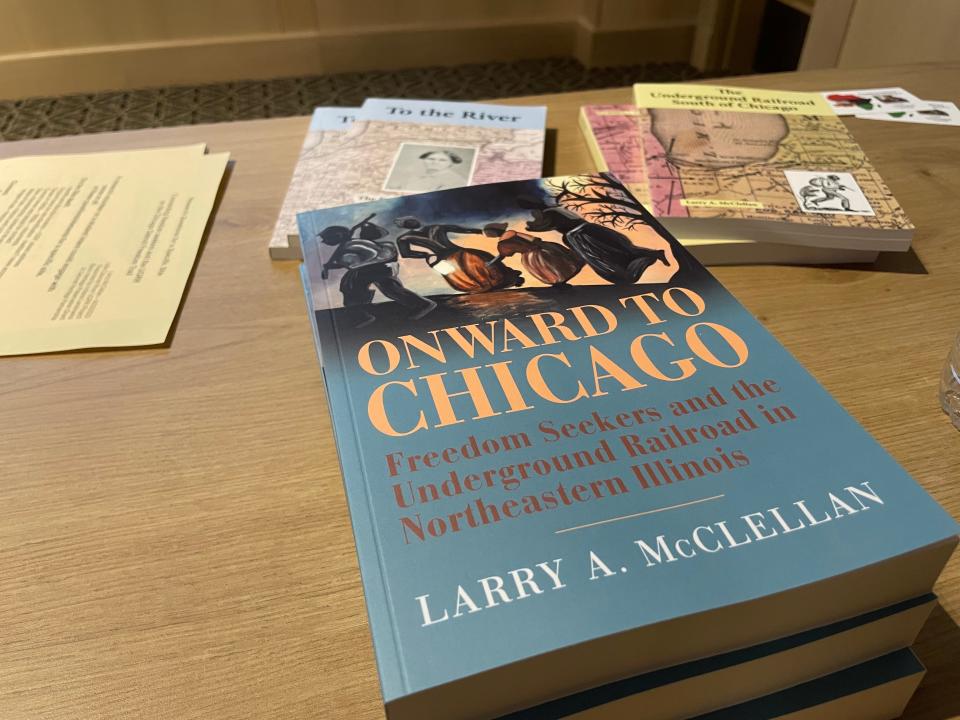

Those stories about the area’s ties to the Underground Railroad became a book, published this September, called “Onward to Chicago: Freedom Seekers and the Underground Railroad in Northeastern Illinois.”

Then McLellan and others began to ask: Where exactly did they go from Chicago?

That question brought him on Wednesday night to the St. Joseph County Public Library in downtown South Bend to discuss the city’s inclusion in a proposed Chicago to Detroit Freedom Trail, which McLellan hopes will one day be recognized as a National Historic Trail by the parks service.

But he expects the effort to take years and require the help of many volunteer researchers willing to excavate stories around local sites with potential links to the Underground Railroad — a network of enslaved African Americans and abolitionists who helped them to flee north.

More: South Bend reparations commission outlines vision for studying harm to Black residents

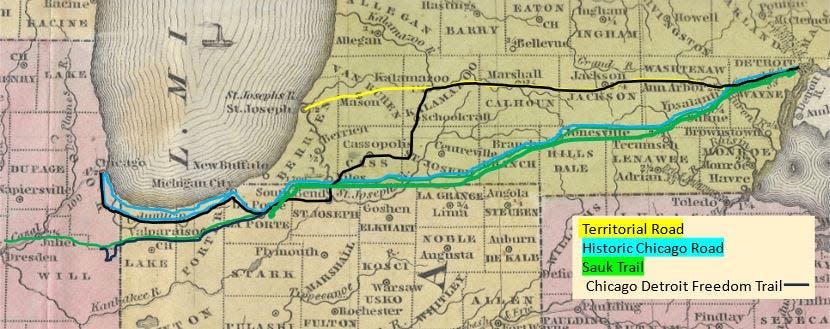

The Freedom Trail would begin with two historic African American churches in Chicago and run parallel to other documented roads freedom seekers took to Detroit, including the Chicago Road and the Sauk Trail. The route would pass through Gary, Michigan City and LaPorte before heading north to Cassopolis and Kalamazoo, then east to Detroit.

McLellan, who did his doctoral work at the University of Chicago and helped to found Governor’s State University, where he taught for 30 years, said he expects at least 35 sites in northern Indiana have ties to freedom seekers. Documentation is lacking, however, with only one site in Bristol an official part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

Some of the connections around South Bend could include the farmhouse of abolitionist and likely station master Thomas Bulla; the 1849 trial of the Powell family, who escaped from slavery to a farm near Cassopolis, where their Kentucky owner found and tried to recapture them but was denied in court; and the Bartlett home, whose owners raised money to buy food and clothing for freedom seekers.

Working with African American elder and scholar Verge “Brother Sage” Gillam, McLellan said he’d also like to include stories from neighboring Elkhart County and east to Fort Wayne. He envisions an additional trail that might be called the Northern Indiana Freedom Trail.

"It’s a way of really, I think, digging deeper into our common humanity," McLellan said, "and realizing that if we are deliberate about celebrating our diversity, we can be much more conscious of celebrating our common humanity.”

Founder of the Little Calumet River Underground Railroad Project, McLellan said his research suggests that 6,000 to 10,000 enslaved people made their way up the Mississippi River Valley into Illinois in the decade before the Civil War. Other routes passed through central Indiana on their way to Michigan. In northeast Illinois, McLellan has found more than 60 sites with ties to freedom seekers.

Estimates say that, between 1820 and 1860, the Underground Railroad helped about 1,000 African Americans in the U.S. to freedom each year. After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 mandated that enslaved people in free states be returned to their owners in the South, it became especially true that to be free, people had to flee to Canada.

“Part of what really gets me with the Underground Railroad stuff is the fundamental humanity of it,” McLellan said. “I’ve got stories of pro-slavery families, and they say, ‘We always thought slavery was just fine,’ and then this family showed up on their doorstep and they needed directions.”

Gillam, who helped to found a 20-site Underground Railroad tour in Cass County, said it’s important to document a history that has often been confined to oral storytelling.

In order for the National Park Service to verify the trail as historic, petitioners must submit written proposals that draw on documents and historical context.

Akila Karanja, a South Bend nurse practitioner who wrote the book “The Emancipated Gospel,” said after Wednesday's event that the Underground Railroad remains for her a profound symbol of self-determination in spite of dehumanizing conditions.

She said it's useful as a metaphor for contemporary struggles.

“People now have to take that mentality that no matter what, I’m going to stop using drugs,” Karanja said. “No matter what, I’m going to stop killing myself with alcohol. No matter what, I’m going to get an education. And if you decide to kill me just because I’m Black and walking down the street and you have a suit on, I’m still going to rise up.

“The Underground Railroad,” she finished, “still exists.”

How to get involved in Underground Railroad project

McLellan encouraged anyone interested to email him at mcclellan.larry@gmail.com or project organizer Tom Shepherd at tomshepherd2001@yahoo.com for instructions about how to begin researching local history. The Little Calumet River Underground Railroad Project also has a Facebook page.

Email South Bend Tribune city reporter Jordan Smith at JTsmith@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter: @jordantsmith09

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: South Bend Underground Railroad ties outlined in Chicago to Detroit trail