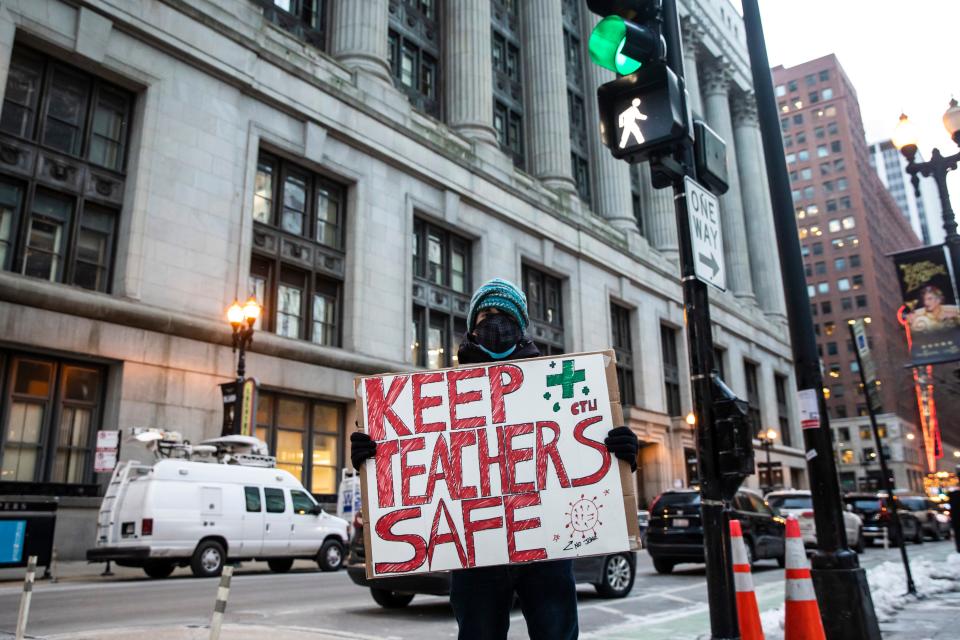

Chicago kids are still out of class after teachers refused to show up. Will other schools follow?

In Chicago, a deadlock between the teachers union and the nation's third-largest school district over COVID-19 canceled classes for three consecutive days this week for most of the district’s 330,000 students.

It's unclear what next week will bring, but some principals have already begun notifying families the cancellations are expected to continue Monday.

The Chicago Teachers Union, which has roughly 25,000 members, voted late Tuesday to shift to remote learning until Jan. 18, or when cases fall. The union is concerned about what members see as inadequate COVID-19 safety rules and is demanding the district require negative coronavirus tests from students and staff before returning to school.

In response, Chicago Public Schools announced it would have to cancel classes Wednesday, neither offering in-person nor remote instruction, because of teachers' refusal to show up. Classes were again canceled on Thursday and Friday. Negotiations about next week remain ongoing.

The conflict has highlighted difficulties around the country, as schools attempt to offer in-person classes amid the spread of the omicron variant. The rocky start to the second semester has renewed tensions between teachers unions and district leaders. But while Chicago's union could inspire other teacher walkouts, its situation is a bit different.

In the Windy City, the conflict stems from an already fraught relationship between the union and district, experts say. And they predict it won't last much longer: Schools desperately need teachers, and students desperately need in-person learning.

How does COVID-19 affect me? Don’t miss an update with the Coronavirus Watch newsletter.

The past decade in Chicago has seen tense budget disagreements and discussions of teacher layoffs, plus conflicts over class sizes, teacher evaluations and the hiring of more social workers, nurses and librarians. In 2012, CTU launched its first strike in 25 years. Since then, it has staged walkouts every few years, most recently a six-day strike in 2019.

“About 2½ strikes in a decade's time period really set the stage for this most recent dispute, which is about COVID-19 but also includes all of the tension and drama that has been boiling up between the union and school district over the last decade,” said Bradley Marianno, an assistant professor of educational policy and leadership at the University of Nevada.

Will the stalemate in Chicago last?

Coming to a reopening agreement for the school system last February was a "long and hard process,” Marianno said. And it resulted in what he called one of the most comprehensive COVID-19 protocol and reopening plans among any district nationwide. When that agreement came to an end in August 2021, the district and union were at odds over how to revise it, setting the stage for this week’s conflict.

But because of public pressure from parents, Marianno doesn’t expect the stalemate will last long. Instead, he said, “the district will have to cave to the demands of the teachers.”

2020 again? For some parents, it feels like it. COVID cases, test shortages are forcing schools to close.

The worsening school staff shortage adds to the pressure, putting teachers unions in a stronger bargaining position, said Eunice Han, an economics professor at the University of Utah. "I'm guessing the school will not have much choice but to offer a remote online setting at least temporarily.”

Melissa Lyon, a postdoctoral research associate at Brown University, said she would not be surprised to see similar walkouts among other teachers unions. The CTU has long served as a kind of bellwether for teacher protests, she said, including strikes in 2012 and 2019 that helped catalyze union action elsewhere.

“Since even the early days of teacher unionism, Chicago has been a key site for teachers union action, and other unions are definitely watching Chicago to see how this plays out,” she said.

Other teachers unions taking action

It has been a rocky start to 2022 in the education world. Districts big and small have been toggling back to remote learning this week, largely because of staff shortages and coronavirus-positive cases. Then there are the challenges associated with mass testing: The screening process requires time, space, people and, of course, a supply of the tests themselves.

Rapid tests, lots of rapid tests: How schools plan to reopen amid omicron surge

While the situation in Chicago is unusual, union-district tensions are bubbling up across the country as the omicron surge and testing headaches throw schools into disarray.

When their school district decided to resume in-person learning Wednesday – after a last-minute delay earlier in the week – the teachers union in Racine, Wisconsin, released a list of demands, including for a temporary return to virtual learning.

The district proceeded with the plan to open classrooms Wednesday, and now the union's members are considering further action. That could involve lobbying and filing workplace safety grievances, said Angelina Cruz, the union's president. But so far, a strike is off the table.

"People construe it as if we don't want to be in the classroom, but I just point out how ridiculous it is that teachers wouldn't want to be in the classroom," she said. The goal of the demands – which also include the distribution of N-95 masks and a stronger testing regime – is to get students and teachers back on campus safely, she said.

In San Francisco, the teachers union on Wednesday also released demands for the district, including that it distribute sufficient test kits and come up with a written plan for responding to positive cases. The district has been “inept and negligent” in its handling of coronavirus testing, said Cassondra Curiel, president of United Educators of San Francisco, in a statement.

More than 620 San Francisco Unified educators were out on Tuesday, and by Thursday the number had shot up to nearly 900. Some of the absences were apparently part of a "sickout" organized separately by a group of educators fed up with the district.

Teachers have valid concern, experts say

Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, the teachers union is “outraged” about what it calls the district’s “eleventh-hour” plan to switch dozens of schools to virtual learning. Families at many of those schools weren’t notified until the early morning the day their children were set to return to classrooms.

Jerry Jordan, president of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, had written a letter to the district last Sunday calling for a seven-day pause on in-person learning amid the omicron-driven COVID-19 surge.

“At nearly every level, today has been chaotic,” Jordan said in a statement Tuesday. “From soaring cases to massive staffing shortages in open buildings, the current situation is untenable.” According to the union’s data, more than 90% of Philadelphia's schools are grappling with shortages, and more than half lack sufficient testing supplies.

"It is clear that the omicron surge in the Philadelphia area is adding yet another layer of complexity to challenges we have been experiencing since the start of this school year," the district's superintendent told the local Fox affiliate. "Yet despite these challenges, one thing remains clear: In-person learning is essential for the physical, social, emotional and academic well-being of our students, especially after nearly two years of trauma."

Some experts believe it's unlikely that teachers unions will take things as far as Chicago's, especially given the renewed interest in the importance of in-person learning.

But if the chaos continues, some unions may feel a virtual "walkout" is their only choice.

"There's good reason for teachers to raise concerns about needing to have high safety standards, but the choice to close schools is a highly impactful one," said Matthew Kraft, an education and economics professor at Brown University. "And it's it's really, really sad that we've come to a place where it feels like that's the only avenue open to try to address those challenges in the short term."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Chicago school dispute, COVID surge spotlights reopening US classrooms