Chief Vernon 'Silent Drum' Lopez remembers his 100 years

MASHPEE — When Vernon "Silent Drum" Lopez was 15 years old, he remembers the Hindenburg hovering over Mashpee Pond.

It was 1937, and the blimp had blown off course, said Lopez, chief of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe. When his mother, Emiline (Brown) Lopez, saw the airship, she quickly scuttled Lopez, and his eight siblings home to Lovell's Lane.

"We were standing on the beach and we see this damn thing floating across the sky — real slow like. It was drifting and going up and down with the wind," he said. "My mother didn’t know what it was. She was afraid."

The image of the Hindenburg made an impression on Lopez. Because, at the time, Mashpee was a "primitive place," he said. There was no running water, homes were miles apart, Route 130 was still a dirt road, and Meetinghouse Road was just a well-walked path.

"There was no black top roads," he said. "There weren't even cars, never mind something like that."

Born in 1922, Lopez will turn 100 years old on Thursday, said his daughter Marlene Lopez, who lives just a few short yards up the hill from his Mashpee home.

More: Tribal Chief Avoids Limelight

While he didn't want anyone to "fuss too much," over his centennial, Marlene Lopez said tribal members and friends will gather at Alice May Lopez Drive at 11 a.m. Thursday, and parade down Meetinghouse Road. The event, which will feature traditional Native drummers singing honor songs in recognition of Lopez' 100 years, is a way for people to thank him for his contributions to the tribe, she said.

"A lot of people look at dad as a person with traditional values," she said. "Many people have learned so much from him and want to show their respect."

Brian Weeden, chairman of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, said tribal members are fortunate to have Lopez — an elder who was raised as chief beginning in 1998. He said Lopez' contributions span the Wampanoag tribal nation, but also the town and the wider Cape Cod community.

“Seeing all the change that’s happened throughout his lifetime, is incredible,” he said. “Not too many people can say they lived here before the town was developed — before there were streetlights.”

For Paula Peters, a Mashpee Wampanoag tribal member, Lopez, is "quietly impactful." As a young woman, Peters recalls Lopez teaching her how to make a drum. From start to finish, Lopez walked her through the process of burning out a log, scraping it clean, and strapping a piece of cow hide he had chosen for her.

"He has always been standing by — ready to give guidance," she said. "His world is Mashpee. He has such a sense of place. His wealth of knowledge lights up the environment around him."

Although Lopez jokes that he earned the name Silent Drum, after miscounting the beats during a series of traditional drum sessions, Weeden said the name comes from a place of deep respect and knowledge.

“He’s one of the only ones in our community that knew how to make a traditional drum at one time,” hesaid. “He did a lot of work to revive the culture of the tribe and through him, we can see how our ancestors navigated, hunted and fished. He continues to pass down tradition.”

Trish Keliinui, a Mashpee Wampanoag tribal member, helped plan the parade, and referred to Lopez as a gentle, kind, and soft spoken soul.

More: Three Sisters Farmers & Crafts Market a chance for Wampanoags to be self-sufficient

“He is very generous with his time and enjoys simply sitting, visiting, watching the wildlife in his backyard, and talking about his childhood in old Mashpee," she said. "Our tribal community, town of Mashpee, neighbors and friends are incredibly fortunate to celebrate our cherished elder."

Long Mashpee Days

During his childhood, time was long, and days were filled with hard work for Wampanoag people, who often met at the Mashpee River, Lopez said. The waterways were gathering places where children could clean up and play, and women gathered water for cooking, and washing clothes.

"We all lived along the river, ate out of the river, drank out of the river, bathed out of the river," he said. "The river was down below us. And we used it for almost everything we did."

Although Lopez lost his father Isaac Lopez "early on," the year and circumstances surrounding his death were not entirely clear. But, without his father, Lopez said his siblings helped his mother with the daily chores. Lopez' job was to cut fire wood for the family.

"There was no coal — no oil — nothing like that," he said. "Every day we went out to cut wood to cook or to keep the house warm.

While Isaac Lopez immigrated to the Cape from Spain, Emiline (Brown) Lopez was Wampanoag — born and raised in Mashpee. Lopez called his mother strict.

"But, with nine children," he said, "I guess she had to be."

More: After town approval of $86K more, Mashpee Veterans War Memorial moves forward

Throughout his young years, Emiline Lopez often sent her son to the nearby general store. The market, which sat just behind where the Mashpee Baptist Church is now , carried goods including kerosene, milk, bread and coffee. In the summer of 1928, Lopez walked to the store along Route 130, and encountered workers he'd never seen before.

"I was 5 or 6 years old and I saw Italians or Germans maybe. They were outside working over where the (Mashpee Wampanoag) museum is now. And they were speaking a foreign language," he said. "I didn’t understand them and they scared me."

Their presence was so rare at the time, said Lopez, that he was fearful enough to travel the long way home.

"It was scary meeting foreign people and not knowing what that was all about," he said. "Back then, it was just family around here."

After his father's death, Lopez, who was nicknamed "Bunny" by one of his aunts, recalls his grandparents Lorenzo "Len" Hammond and Lillian Hammond, occasionally traveling the roughly five miles from Cotuit to Mashpee to help his mother with the children. Len Hammond, also served as a Wampanoag chief, he said.

"Whoever was interested (in being chief), would stand up in a row. Then the tribe would point out the one they wanted by standing behind that person," he said. "Whoever had the most — they were chief. He was chosen by the people."

Also a plumber, Len Hammond worked the wells, and took care of tribal families, as well as his own. That was the culture of Mashpee at that time, said Lopez.

More: Hiking Cape Cod: The Mashpee River Woodlands

"Everybody watched out for everybody else," he said. "If someone knew you had a problem, they didn't ask about it. They’d just go right down there and help."

The draft - Lopez heads overseas

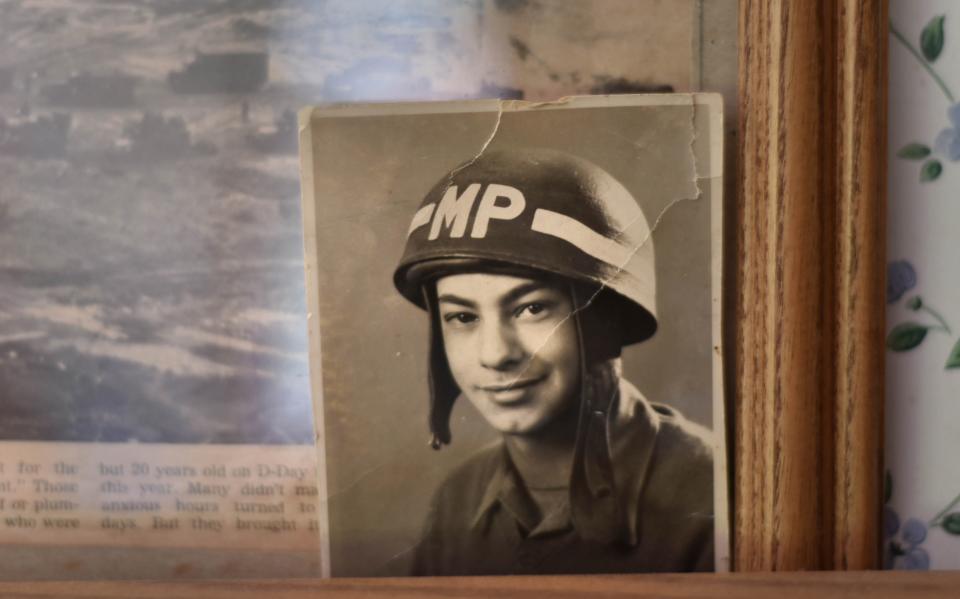

Just after his 20th birthday, Lopez was drafted into the Army. While he had never strayed too far from Mashpee, he was headed overseas.

"I was working up by Camp Edwards and I got my notice," he said. "They sent me down to Louisiana for training — boot camp."

From there, Lopez went to Virginia Beach, where he learned how to scale ships in the harbor. Troops would scamper up and down, the thick, twisted, rope ladders, as waves seesawed vessels in and out of the water.

"It was a practice run, you know," he said. "We were getting ready for the war — but we didn’t know that yet."

After infantry and military police training, Lopez shipped out of New York and traveled to England, along with three other ships chock full of young men.

For six months he remained in England, with German planes "dropping bombs all over the place," Lopez said. As the United States sent supplies like food, clothing, ammunition, guns — and even tanks — military police formed camouflaged motorcycle convoys at nightfall and ushered goods across England's countryside.

"We would be sleeping and all of a sudden a guy would come by and give you a kick and you were on your way to some place or another," he said.

The Battle of Normandy

On June 6, 1944 — a date known to many as "D-Day" — Lopez joined the roughly 156,000 American, British and Canadian forces that fought the Germans off the coast of France’s Normandy region.

A part of the fifth wave, Lopez remembers his descent into the neck-high waters of the English Channel, just off Omaha Beach. He carefully waded towards the shore —his gun, ammunition, and field pack weighing him down further into the water.

More: Elderly Cape Cod veterans forced to travel long distances for qualifying exams for benefits

"It was touch and go, I’ll tell ya. You didn’t have much chance to plan anything. Snipers were behind a damn tree trying to shoot at ya and you didn't know they were there," he said. "It was all a new experience for me. Never dreamed anything could be like that."

Eventually, allied survivors successfully drove German troops back, and as a member of the Military Police, it was Lopez' job to build stockades for German prisoners. Luckily, Lopez said, his company only lost a few men.

"We were all young. Some of us never been so far away from home," he said. "My 23rd birthday was a couple of weeks after the invasion. I was very lucky to see that day."

Lopez heads home to Mashpee

Shortly after D-Day, Lopez developed a skin disease and was hospitalized in France. Throughout the disorder, he remembers being able to remove long swaths of skin from his arms and legs

"I could pull it right off my body. Like a snakeskin," he said.

After a series of oatmeal baths, he was cleared to head home, barely making the ship before it pulled out of port.

"My duffle bag and everything was already on the boat," he said. "All they was waiting for — was me."

More: Food pantries for veterans extend from Hyannis to Eastham and Falmouth

When the boat pulled into Fort Devens in Boston, Lopez was discharged from service.

"They said, 'Okay, you’re all done. You’re out of the service.' Just like that," he said.

Luckily, he brought a duffel bag that held his personal belongings from the ship — the contents containing an Italian pistol and "a beautiful side gun," he said.

"Later on, I got hard up, and I took them down to Hyannis and pawned them,” he said, a grin spreading across his face.

Wasting no time, Lopez caught the first train to Cape Cod, and a local mail carrier gave him a ride to his front door.

"My mother saw me and started crying," he said.

Lopez later in Life

From there, Lopez spent a good portion of his life working in clothing and shoe-dying factories in Brockton, Quincy, and Boston. The longest job was at the Avon Cut and Die.

During that time, he met Mary Stanley, who would later become Mary Lopez when the couple married in 1947. The duo would have two children — Marlene Lopez and Ralph Lopez. Described as a free spirit, Ralph Lopez died after a battle with bone cancer in 1992.

"He learned how to play a guitar all on his own. He was independent and he loved music," said Lopez. "You never knew where he was going to be. But he did get around, I’ll tell you. That was his lifestyle."

After both his children left the house, Lopez helped his brother-in-law Jack "Johnny" Stanley build his ranch-style home in 1971, and moved back to Mashpee. Later, in 1982, the duo would build Marlene's home. For a bit, Lopez commuted to work off-Cape, but eventually worked at the State Fish Hatchery in Sandwich for a decade, retiring at age 70.

While they spent many years together, Mary Lopez, who was a master gardener, photographer, and the Indian education director in Mashpee, died in 2006.

"He and mom went to all kinds of schools and talked about the tribe and about our history," Marlene Lopez said. "Dad did all kinds of activities here in town, repairing things and fixing things. And then he had his army reunions too that they traveled to. Everywhere they went, they brought their culture and knowledge."

Passing on the title

Lopez was chosen and raised as chief after the passing of Chief Vernon “Sly Fox” Pocknett. In 1956, before Pocknett, Earl Mills was also chosen as chief. Traditionally, they will all hold the honor for the entirety of their lives.

But on his 100th birthday, Lopez said he will retire that title, and tribal clan mothers , along with tribal elders, will begin gathering names to raise a new chief. Marlene Lopez is a clan mother, and represents the Lopez family as part of the rabbit clan.

"They might still call me chief. But once I turn 100, the clan mothers take over," he said. "They do it anyways pretty much."

For now, Lopez is content sitting quietly on his backyard bench, with chipmunks and rabbits zipping under the trees, occasionally scooting around his feet and through the grassy fields he calls home.

"I sit out here quite a lot in the sun. I reminisce about my life, the war, where I’ve been," he said. "I realize nothing stands still. Everything is on the move and it doesn’t take long to get lost in the shuffle. But I enjoy being here and meeting different people."

This article originally appeared on Cape Cod Times: Mashpee born, Chief Vernon Lopez celebrates his 100th birthday