My child was bullied and I didn't speak up. I wish I had

As a single parent, I had to come up with a creative way to get through the summer. Camp nursing doesn’t pay well, but it sounded like fun and one of the perks was that my children could go for free. Another one: I wouldn’t have to cook. I arranged a month off from my job as a home care nurse in Baltimore thinking it would be a great experience for the three of us. My son, 10 years old, was excited about the trip. My daughter, at 12, was not.

The drive to Maine was tiring and ended with a harrowing stretch of winding roads at night in heavy rain. We could not find lodging and had to keep driving. It was such a relief to finally arrive, even my daughter was glad to be there.

The first few days were busy, getting to know the campers and staff, organizing the children’s medications, soothing the homesickness, treating the rashes and tick bites, the stomach aches, the menstrual cramps.

I saw my children at meals and when they came into the infirmary to say hello, but had little time to check up on them. Neither of them had ever had trouble making friends. They were outgoing and self-confident in new situations. I trusted the counselors to tell me if there was a problem.

So, it was a surprise when I saw my daughter sitting alone at lunch, her entire cabin of campers at another table, the counselors not seeming to notice her absence. When I asked about it, she brushed me off, saying she’d been late getting to lunch and there was no room at the table.

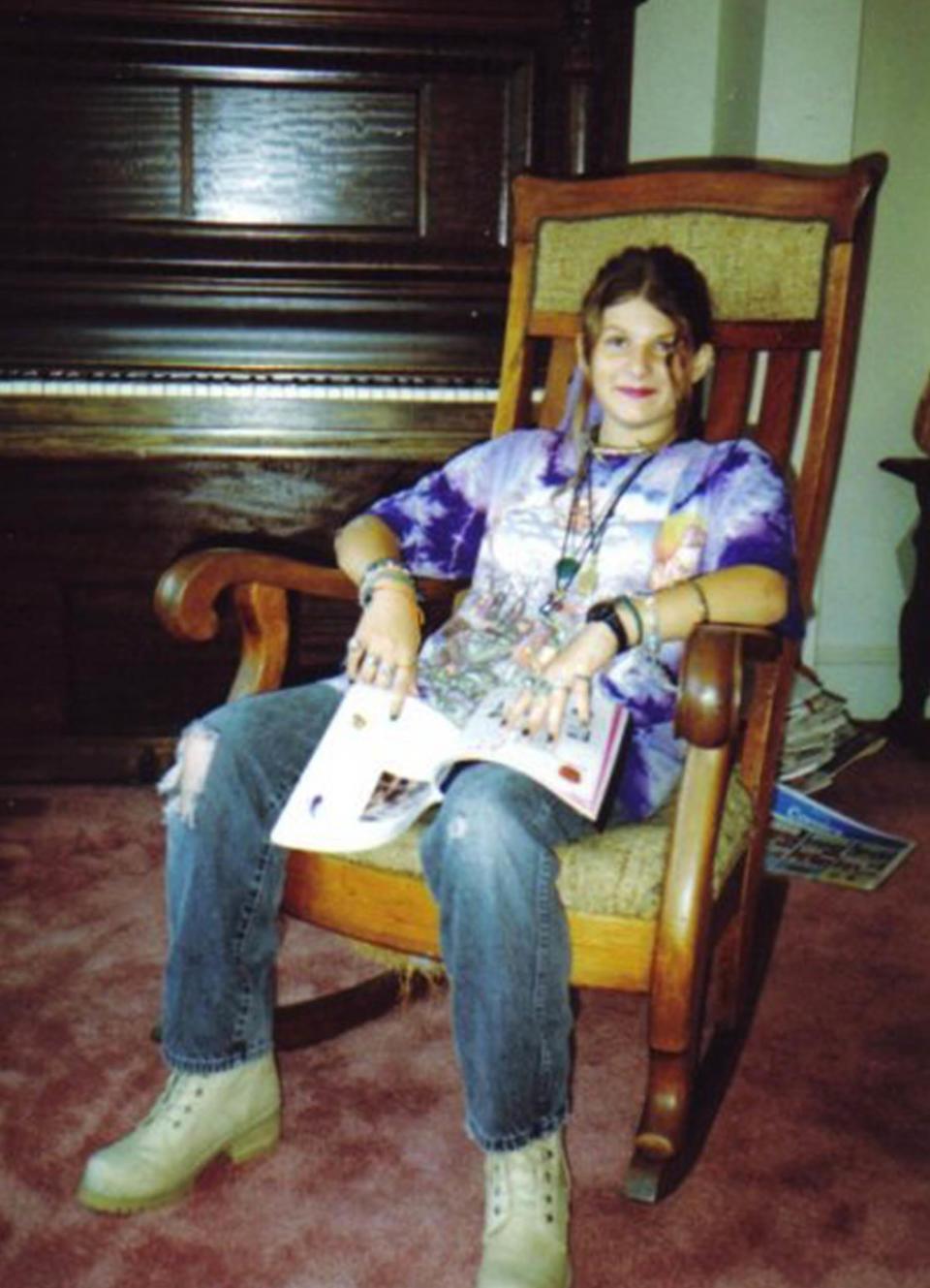

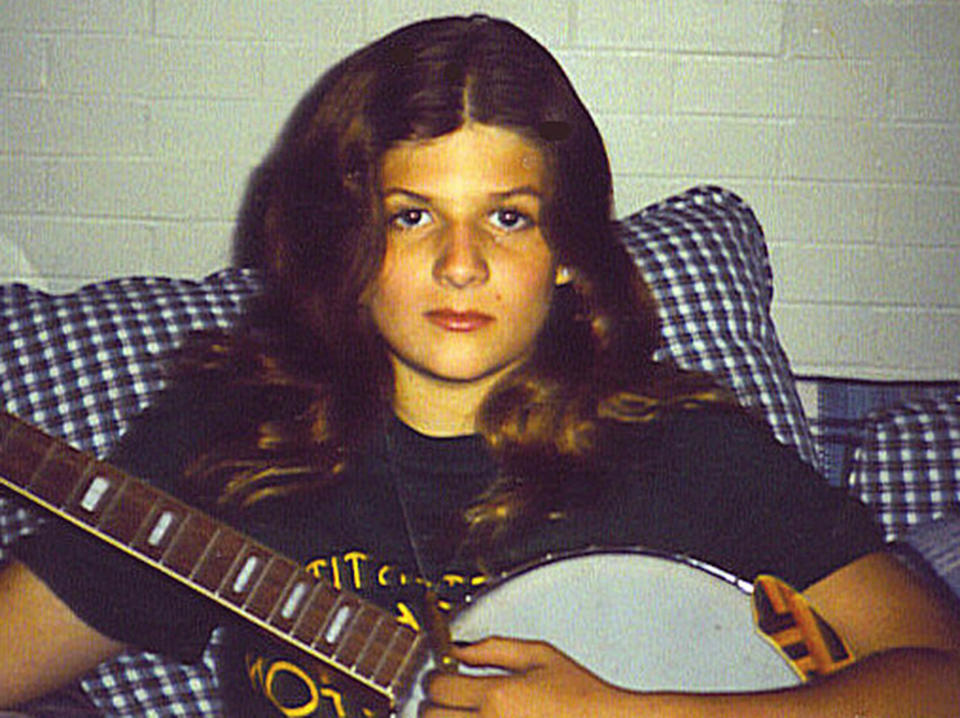

It wasn’t until two weeks into the month-long session that Lydia confided in me. Her cabin mates had found her journal hidden under her mattress. They’d read aloud her poetry. They’d shrieked at passages about her affection for a girl at her school. She’d been suffering their ridicule and ever since. They called her dyke and lesbo, freak and loser. They were dramatic about hiding from her view when they changed clothes. They avoided being near her.

She told me this only because of an incident where several of the girls stole a box of candy bars from a delivery truck and tried to get her to share the loot so she couldn’t tell. When she declined the candy, they threatened to collaborate on a story that it was Lydia who’d stolen it. “Who do you think they’ll believe, loser?”

I wanted to go right then and confront the girls. I wanted to chastise the counselors for not intervening in what had been nearly two weeks of harassment. “You don’t have to put up with this. We can leave here tomorrow,” I said. I was so angry I didn’t think about how my son might feel about that.

But Lydia didn’t want to leave. “I’m not going to let them ruin this for me.” She’d been enjoying some of her activities: fencing, creative writing, woodworking, even, to my chagrin, riflery.

All these many years later, it hurts to think about it. I wonder how it happens that a pack of snarling girls forms so quickly when there’s an opportunity to turn on one of the group.

What was the appeal of causing pain to my child? What made them want to hurt her?

I’d love to ask their adult selves, but it’s not likely they’d remember Lydia. There were probably many others they’d treated with an equal measure of disdain. Do they still? Or have they mellowed, softened with time? Do they have children of their own? What are they teaching those children?

I’m still, after all these years, appalled at myself for not bringing the problem to the camp’s administrators. Lydia had made friends with some older girls. I should have demanded her move to another cabin, regardless of the age difference. She corresponded with one of those friends for several years after camp. I believe that correspondence continued until my daughter’s death by suicide.

Meanwhile that summer, I saw another child, a pale thin boy, being bullied mercilessly as the counselors looked the other way. What, I wondered, had been their training? On a canoe trip, a group waited for the boy and overturned his canoe. Some held him down while others covered him, head to toe, in mud. One counselor later told me he was tempted to call that boy’s parents anonymously and say, “If you love your child, come get him now.” Why didn’t he? Why didn’t I? I reasoned I might further embarrass the boy. He seemed to want to make light of it and I didn’t want to cause him further embarrassment. But it was my responsibility as an adult to intercede.

Despite the more than two decades since my daughter was bullied at camp, I feel the pangs of guilt all over again when I hear statistics about the teen mental health crisis, or stories about young people who ended their lives after being harassed at school.

“There’s no question young people are telling us they are in crisis. The data really call on us to act,” Kathleen Ethier, director of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s adolescent and school health division, tells TODAY.com. The CDC’s research found that 30% of girls polled have seriously considered suicide. This is double the rate among boys and up almost 60% from a decade ago. Among LGBTQ youth, almost 50% report having seriously considered suicide and nearly 1 in 4 attempted suicide in 2021. We can no longer afford to remain silent. I could not afford my silence 20 years ago. While my daughter’s suicide was not a direct result of bullying, I will never forget the hurt she felt at being ostracized at that camp. I doubt she ever forgot it either. I wish I could tell her how sorry I am.

If I could, I would apologize to that pale thin boy who was covered in mud and likely suffered other humiliating acts of inhumanity. I hope he is healthy and content. I hope he will not remain quiet when he sees a child in need of the safety of a caring adult.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com