Child gun violence is rising in the Memphis area. Survivors, doctors say the toll is immense

The doctors at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital are mad. They’re mad because kids with gunshot wounds are coming through their doors at alarming rates.

They’re mad because they see it as a public health crisis that’s not being adequately addressed. They’re mad because many of the victims are the same age as their children and have wounds that will irrevocably alter their lives. Children struck with bullets have needed breathing tubes and brain surgery. They’ve been paralyzed and lost limbs.

The issue is not endemic to Memphis. From 2019 to 2021, the number of children and teens in the U.S. killed by gunfire rose 50%, according to the Pew Research Center. But the local numbers are still dismaying. In 2019, Le Bonheur treated 90 patients for gunshot wounds. In 2020, that number jumped to 134, and in 2021, it climbed to 158, before decreasing to 150 in 2022. As of Dec. 6, Le Bonheur had treated a record 165 gunshot victims in 2023 ― and these numbers don’t include the youth who are treated elsewhere or pronounced dead on the scene.

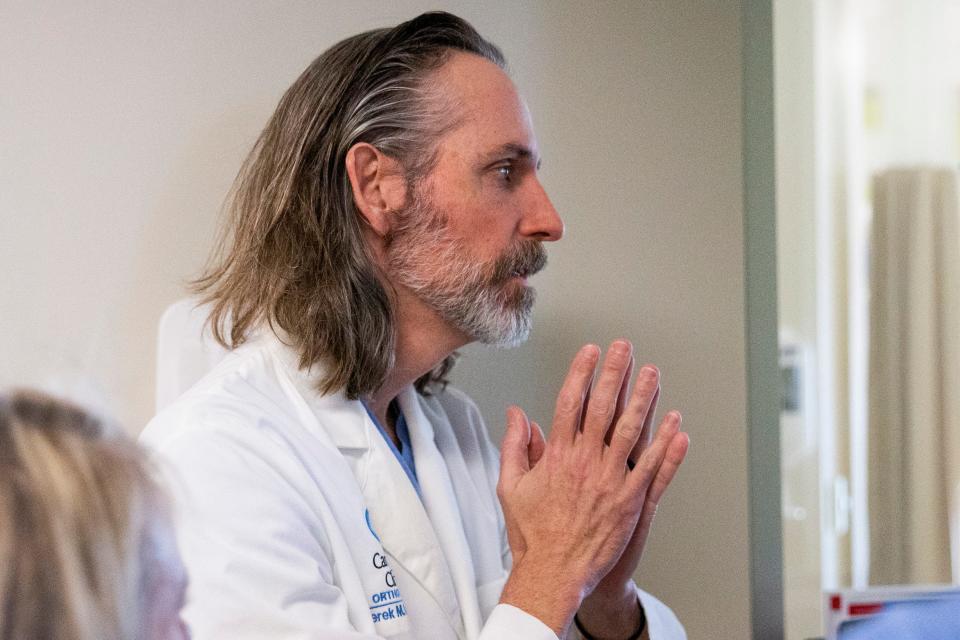

“If a kid is injured, I get the opportunity to try to take care of them,” said Dr. Derek Kelly, a professor of orthopedic surgery at Campbell's Clinic and Le Bonheur. “I just wish I didn't have to take care of so many injured by guns. Can I take care of a kid who falls on the monkey bars? Can I take care of a kid who has an injury playing sports? Why do I have to take care of a kid who needlessly was shot with a gun?”

Most of the patients Le Bonheur doctors treat survive their wounds. In 2022, about 5% of the gunshot victims Le Bonheur saw died. But with life can come a demanding aftermath, the daunting physical and psychological challenges that arise when you’re shot at such a young age.

This is the story of a young man who was accidentally shot as a boy. It is a compilation of the thoughts of Le Bonheur doctors, who desperately want this crisis to be addressed. And it is a snapshot of how the scourge of gun violence is affecting the youngest, most vulnerable members of this community.

47 transfusions

Nov. 29, 2009, started just the way Chance Futrell could have hoped. The energetic 10-year-old went deer hunting with a friend, and any time he could hunt, he was happy. But after finishing and returning to his friend’s parents’ house in Mooreville, Mississippi, Futrell grew nervous.

His friend was waving a rifle around like it was a toy, unaware that it was loaded. Knock it off, Futrell told him. He didn’t. Instead, he accidentally fired it; and the bullet struck Futrell in the upper left leg, shattering bone and bursting his femoral artery.

Futrell collapsed.

“You shot me,” he cried.

His friend sprinted out to fetch his grandfather, who lived across the street, as Futrell writhed on the floor and blood gushed from his wound. The grandfather called 911, and an ambulance sped Futrell to the hospital in Tupelo, just 12 minutes from Mooreville. But the Tupelo hospital wasn’t equipped to handle such a traumatic gunshot. The elementary schooler had lost a dangerous amount of blood. He had an enormous wound in his leg, and a pivotal artery had burst. Bone fragments and shrapnel had spread throughout the lower half of his body, and he had suffered serious injuries to his groin area.

Futrell’s wounds required the attention of a Level 1 Trauma Center, and the nearest one for pediatric patients was Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis, roughly two hours away.

He received 47 blood transfusions before arriving at Le Bonheur. Futrell didn’t feel pain, the shock distracted him from that, but his entire body felt hot ― really hot. At the time, he didn’t understand the severity of the situation. He didn’t understand that he was close to amputation, or even death. But he did think about the future. He thought about how much he loved playing sports ― how much he loved baseball, soccer, and basketball. His sports career, he feared, was over.

After making it to Le Bonheur, Futrell saw his parents before undergoing surgery and tried to console them.

“Everything is going to be alright,” he said. “I’ll see y'all when I wake up.”

Then, Futrell was put to sleep for an operation. It was the first of 18 surgeries he would undergo.

'Your son is lucky'

The first surgery lasted six hours. Afterward, a surgeon approached Futrell’s mother.

“Your son is lucky,” he said. “He’s going to make it.”

In some ways, Futrell was lucky. He hadn’t just avoided death; he had avoided amputation. His blood vessels and nerves hadn’t been damaged beyond repair, so salvaging his limb was possible. Kelly, one of the surgeons who worked with him during his time at Le Bonheur, estimated that the shot was centimeters away from causing him to lose his leg.

But luck is a relative term.

Futrell had a colostomy bag inserted into his intestine to collect his excrement because a portion of his groin region had to be reconstructed. He underwent washouts, efforts to remove dead and dying tissue and prevent infection in his giant wound. He had an external fixator placed, a temporary measure to stabilize the fracture in his leg.

The severity of the injury, however, didn’t surprise Kelly. At the time Futrell was shot 14 years ago, it wasn’t all that uncommon for children to end up with atrocious gunshot wounds. Though he had only been in practice for a year, Kelly had seen pediatric victims of gun violence before, and he suspected he’d see more in the future.

But he never imagined he’d see as many as he is today.

Night terrors

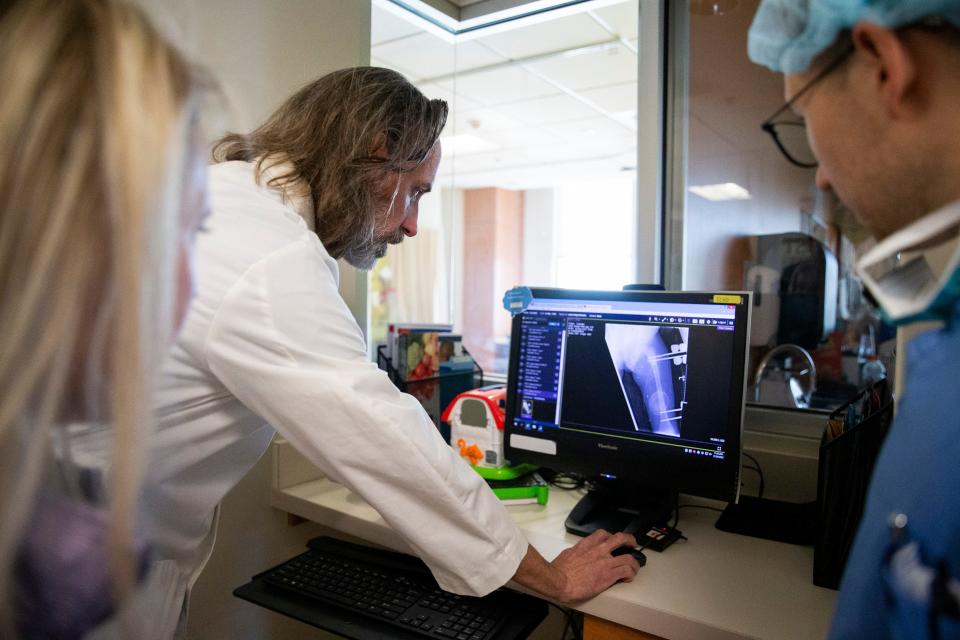

At Le Bonheur, treating patients for gun violence has become a regular occurrence. The first time Kelly spoke with The Commercial Appeal, he had just treated a teenager for a shot to the femur, and that afternoon, one of his partners was poised to treat a toddler with a gunshot wound in the thumb.

The injuries happen in various ways. Children have been accidentally shot, as Futrell was, by someone who didn’t understand the power of firearms. They have unintentionally shot themselves, after finding guns stored carelessly. They have, in some instances, been shot after growing involved with gangs. And many times, they have been the unintended targets of bullets meant for another, suffering tremendously because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

More: How a new Shelby County facility could address public health, safety and justice

According to Le Bonheur’s data, 33 of the gunshot wound patients it treated in 2022 had injuries that were considered accidental, one came from self-harm, and another 116 had wounds that stemmed from assaults ― a category that includes drive-by shootings.

“They're all awful, because I mean, it's a kid who got shot and there's really no reason for that,” Kelly said. “The problem is, they're so commonplace now that they don't really stand out. It’s just, 'Okay, we’ve got another gunshot today, or we’ve got two more gunshots today.'”

The psychological challenges arising from these gunshots are severe. Children and adolescents affected by gun violence can grapple with depression and anxiety. They can develop acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. They’ll have night terrors and horrible dreams that cause them to relive the shooting repeatedly and wake up abruptly. Their nervous systems will constantly be activated, and they’ll be traumatized by sudden sounds after leaving the hospital, like the ringing of a school bell.

Sometimes, the victims won’t know who shot them, and they’ll struggle to trust their friends or family. They won’t always feel safe in their own home.

“Something that doesn't get talked about as much is the mental health aspect of being shot,” said Dr. Regan Williams, Le Bonheur’s medical director of trauma services, and an associate professor at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center. “It really does cause lifelong problems for them and their families.”

For the last few years, Le Bonheur has done its best to address these mental health problems stemming from shootings. Kiersten Hawes, Ph.D., is a trauma mental health counselor at the hospital and the BRAIN Center clinical director of trauma counseling, and she oversees the mental health and counseling services that the hospital provides to trauma patients and their family members.

Le Bonheur offers them free, unlimited counseling services once they’ve been admitted into the hospital, and they have the option to continue receiving the support in an outpatient center after being discharged. In the last three years, Hawes and her team have conducted over 3,000 counseling sessions for trauma patients and seen positive outcomes.

The work isn’t easy. If an injury is especially serious, it can cause a patient to give up an activity they love temporarily or permanently. For many of the gunshot victims at Le Bonheur, sports serve as a form of therapy. But injuries keep them on the sidelines, so Hawes must help teach new ways of staying involved with their teams and finding joy.

“There’s this aspect of grief when it comes to experiencing trauma,” Hawes said. “They’re trying to adjust to this new normal… I think that's the most challenging thing. We've seen the adjustment that comes with it.”

'I want to go home'

It was an adjustment made by Futrell. His initial stay at Le Bonheur lasted five weeks, and he wanted to leave the hospital. He wanted to be able to play sports and hunt again.

“I could ask and ask and ask, 'when am I getting to go home,'” he said. “And every day something was new. I would wake up from surgery and have to do something new or take a new medicine.”

When the time to leave Le Bonheur came, Futrell wasn’t sent home. He was sent to a rehab facility, where he spent another few weeks, and his eventual return home didn’t come with a return to normalcy. Futrell couldn’t go back to school for several months. He was still in pain and confined to a wheelchair. He had to attend physical therapy regularly.

“I wanted to get up and walk; I wanted to get out and run,” Futrell said. “I couldn’t. It hurt.”

Healthcare news: 30 years post-transplant, this Tipton County man considers his life an 'ongoing miracle'

Roughly six months after initially leaving Le Bonheur, Futrell returned to the hospital, to have his colostomy reversed, his fixator removed, and a rod inserted into the damaged leg bone. Because he had lost so much of his bone when he was shot, surgeons had to shorten it, and then put the rod in, to better the bone’s chances of healing. This operation significantly improved Futrell’s condition and helped him shift from a wheelchair to crutches, but the bone didn’t fully heal, which meant he had to return for another surgery. Within the next year, Kelly and his team removed the rod, recleaned the site of the fracture, took a bone graft from his pelvis and packed it into the damaged bone, and inserted a new rod.

Time passed and the bone healed. But because part of it had been removed, his left leg was now shorter than his right one, and he was nearing his teenage growth spurt ― which meant he had to undergo a surgery that would slow the growth of his right leg, so the left one had time to catch up to it.

The surgeries were taxing, but throughout this period, Futrell showed resilience. He strived to recover, so he could get back to hunting and playing sports, and he impressed Kelly with his positivity.

Futrell refused to let the injury ruin his life. While confined to a wheelchair, his friends pushed him around and helped him. He still went to his sports teams’ games, even when he couldn’t play.

“One of these days,” he told himself, “I’m going to get back to where I can do all this again.”

Where should a gun be stored?

The rise in injuries that has taken place since Futrell’s incident raises a question: What’s behind all the child gun violence?

Many of the accidental shootings stem from haphazard storage. Children exploring their surroundings have unintentionally harmed themselves after discovering loaded guns in dresser drawers and car glove compartments. They have found them, even, on TV stands and coffee tables.

“A lot of families will store it in an open-drawer nightstand,” said Dr. Nick Watkins, who works in pediatric emergency medicine at Le Bonheur and is the hospital's Medical Champion of Injury Prevention. “Imagine a toddler who's two-and-a-half feet tall. The nightstand’s two-and-a-half feet tall. They can easily pull up in a drawer and reach in… You'd be surprised by the amount of open access I've heard about from families after their children come in… with an injury.”

Watkins is a former gun owner himself, having used a rifle for deer hunting. But he no longer owns one, in part because he doesn’t currently hunt, and in part because he now has a mobile, two-and-a-half-year-old daughter.

“A one-year-old, a two-year-old, can squeeze a trigger,” Watkins said. “I don’t know if you’ve seen a baby’s grip strength before, but they can squeeze and hold onto things… The safest place for a gun is outside the home.”

'Because I believe in it': Inside the mentorship nonprofit run by a Memphis police officer

But if you are going to keep a gun in the house, he continued, it’s imperative to keep it locked away in a safe or storage box, with the ammunition kept separately. For those who own guns for defense purposes, such methods might seem impractical.

Watkins will tell you some safes can provide fast access. And a gun in the home - especially one kept out in the open ― has the potential to do more harm than good. Per the nonprofit Everytown for Gun Safety, nearly 130 children and teens die from unintentional gunshots every year, and access to a gun triples the risk of suicide.

“If you look at how often you have to use a gun for self-defense, versus how often a child accesses a gun for self-harm or accidental or intentional injury, the injury component outweighs the need for self-defense,” Watkins said. “It's overwhelming when you look at the evidence.”

But storage addresses just one component of a multi-faceted problem, and the rise in child gun violence has come as the overall crime rate has risen. According to Don Crowe, an assistant chief of police with the Memphis Police Department, crime in the Bluff City was decreasing prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Then it grew, and this year, Memphis is on pace to eclipse the previous record crime rate set in 1996.

“It parallels the other trends,” Crowe said of pediatric gun violence. “We see that violent crime started going back up… and unfortunately, those crimes also involve people under the age of 18.”

The child gun violence rise also comes in a state that’s loosened gun laws, which some believe have led to a proliferation of guns on the streets. For example, in 2013, Tennessee passed a law that allowed people to keep guns stored in their cars without a person in them. Since then, Crowe noted, the number of guns stolen from cars has ballooned.

“Go back to 2014, we had about 350 guns stolen out of cars,” he said. “Last year, we had 2,400… And where do those guns end up? Mostly in the hands of the wrong people.”

A larger picture

The Le Bonheur doctors The Commercial Appeal spoke to want more to be done about child gun violence, but to them, it’s not a political issue. It’s a public health crisis that should have a public health approach, and they want to see more common-sense gun laws: data-driven decisions that could make youth safer.

Doctors mentioned strong background checks and safe storage laws. They spoke about temporary transfer orders, which could temporarily remove guns from the hands of people at risk of harming themselves or others.

They aren’t campaigning for sweeping gun bans. Kelly is a gun owner. But with children repeatedly entering Le Bonheur after being shot, they want the issue addressed.

“What we have right now is leading to more gun trauma for kids... What we're doing now is not working,” Kelly said. “There has to be a way to allow us the freedoms that we enjoy in this country while protecting kids from gun violence… And I think that there are enough sensible people… that can reach some compromises that do both of those things. But throwing your hands up and saying this is just a consequence of our freedom, that can't be the right answer.”

That’s not to say there is just one answer. The child gun violence rate has risen amid rampant local poverty that afflicts youth, and in 2022, the child poverty rate in Memphis was 32.7%. That same year, Memphis-Shelby County Schools identified nearly 3,000 students who were homeless and said the real number was likely higher.

Could poverty be contributing to the high child gun violence incidents and overall crime in Memphis? Certainly.

“A lot of times, we make it a separate issue, but it's deeply intertwined to things like poverty, access to adequate health care, food insecurities, other versions of crime and violence… mental health disorders,” Watkins said. “I don't think will truly fix each individual part of that, without fixing the whole picture.”

Until that picture is fixed, children will continue to be severely wounded with firearms, as Futrell was more than a decade ago.

In many ways, his story is one of triumph. In eighth grade, he was able to start playing sports again, and his condition continued to improve as time passed. He has made a remarkable recovery, and he has nothing but praise for the doctors at Le Bonheur. Today, Futrell works as a UPS driver. He continues to hunt regularly, and in the future, when he has children of his own, he intends to teach them thoroughly about the importance of gun safety.

But reminders of the incident haven’t vanished. Futrell can often sense when it’s going to rain because he’ll feel an ache in his old wound. He’ll have back pain. And most years, around the time he was injured, Futrell will have a dream, in which he gets shot at or hurt. He’ll then wake up feeling the same sensation he had on Nov. 29, 2009 ― when a friend altered his childhood because he was playing with a gun.

“I still have complications with it,” Futrell said. “I can’t ever say it will be out of the rearview mirror.”

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: Child gun violence in Memphis is on the rise. Here's a look at why