'My childhood friends': Winter Haven grads, Army officers died in Vietnam17 months apart

The scene was unspeakable. Seventy-eight American bodies lay sprawled for a hundred yards or so along the trail, framed by the encroaching jungle. Eighteen lay piled on top of one another in a small circle, site of a desperate last stand. The NVA had stripped some of the bodies. Others were mutilated, their eyes gouged out or their ring fingers chopped off. A few survivors had feigned death. One soldier had remained motionless as the enemy shot him three times in the back; another did the same while his finger was severed with a trench knife.

The ground was splotched red. Some of the dead had hollow cavity wounds, brains literally blown from their heads…And here was Rich Hood, a small hole behind one ear, as though he had been executed point blank. His ammunition gone, Hood had fought to the end with trip flares.

From The Long Gray Line: The American Journey of West Point’s Class of 1966, by Rick Atkinson

***

Between 1965 and 1974, 80 men from Polk County lost their lives in Vietnam, all but a few from combat. They ranged in age and rank from an Army private who was 18 to an Air Force colonel who was 46, and represented all service branches. A quarter of those killed were still teenagers. The majority were in their 20s, their lives barely lived, their futures vaporized.

Two were my childhood friends – Richard Hood and Johnny Hays. While the death of any member of the armed services is uniquely tragic and equally noteworthy, on the occasion of Memorial Day I wish to honor the pair I knew best, holding them out as representative of all that was given – and all that was lost.

Johnny and Richard were sons most parents would proudly claim – responsible and respectful, amiable and studious, admired by peers and teachers alike. Both were kind and solicitous of others, attributes not always associated with school-age boys. Each was student council president at Winter Haven High, member of the Honor Society, selected for Boys State – personalities equally serious and gregarious.

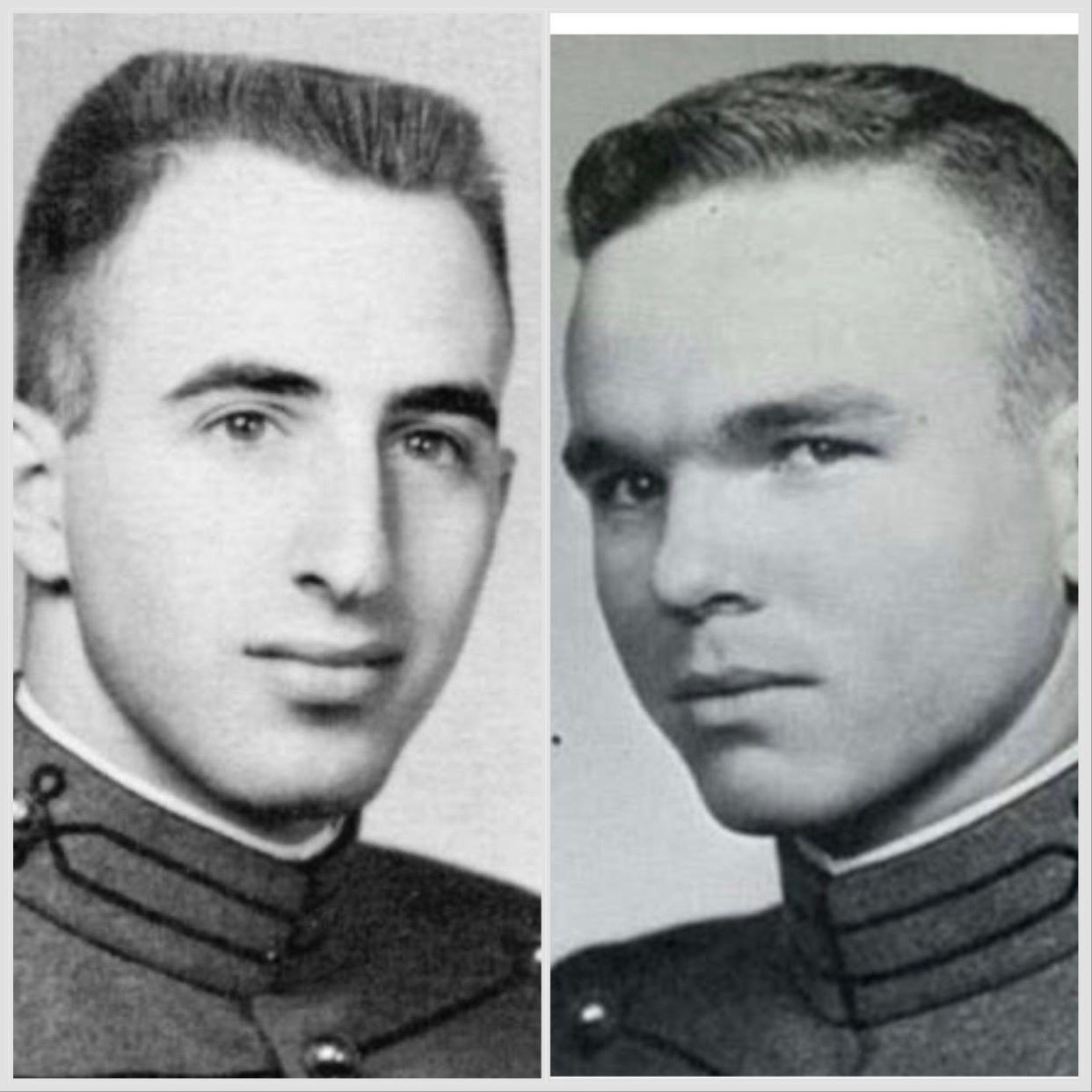

But what soon set them markedly apart from their classmates was that each was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and following further training after graduation, each was deployed to Vietnam.

Neither Richard nor Johnny came marching home again. Both died in combat a few months apart, and both are buried a few yards apart in Lakeside Memorial Park, north of downtown Winter Haven.

Despite sad memories Lakeland Green Beret Kenneth Conklin 'would do it all again'

'The best that ever served' Winter Haven man once commanded elite Tiger Force in Vietnam

Retired Air Force Maj. Gen. Jake Polumbo 'Honor the service of those sons and daughters' who sacrificed

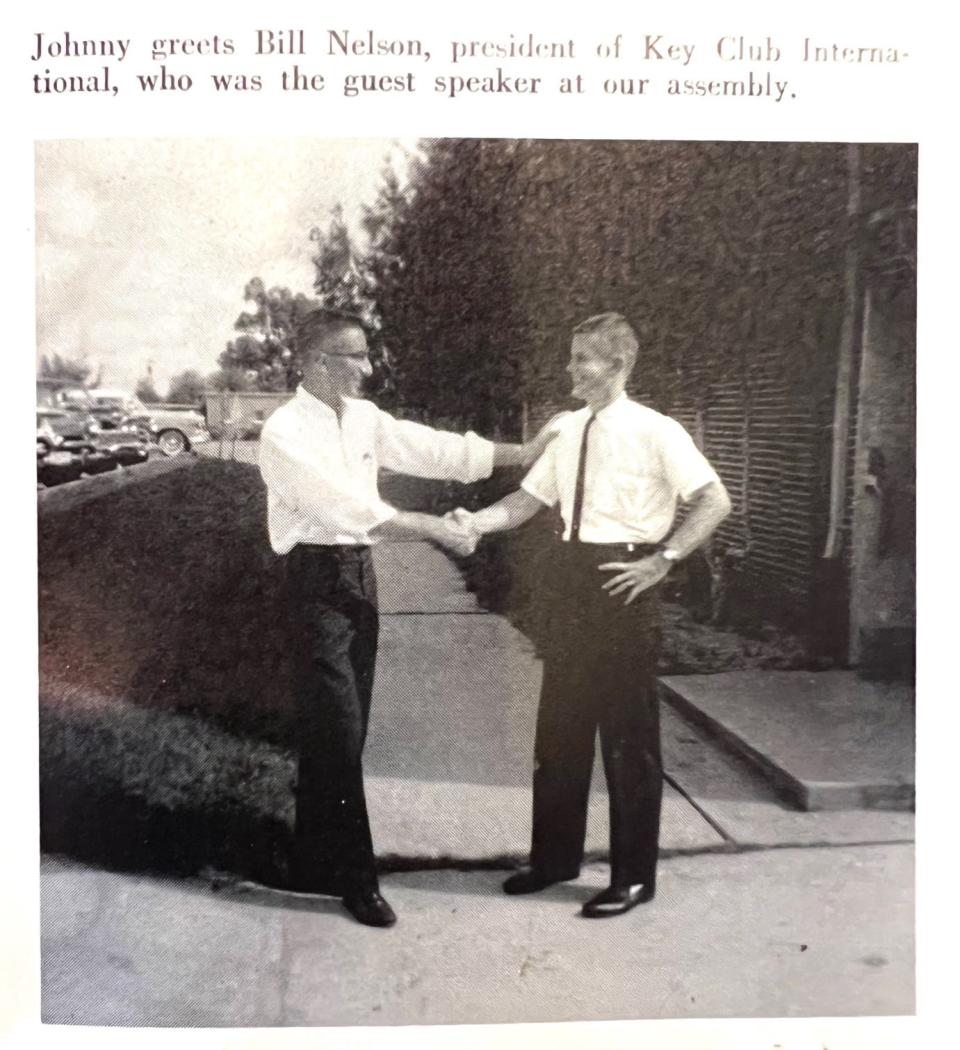

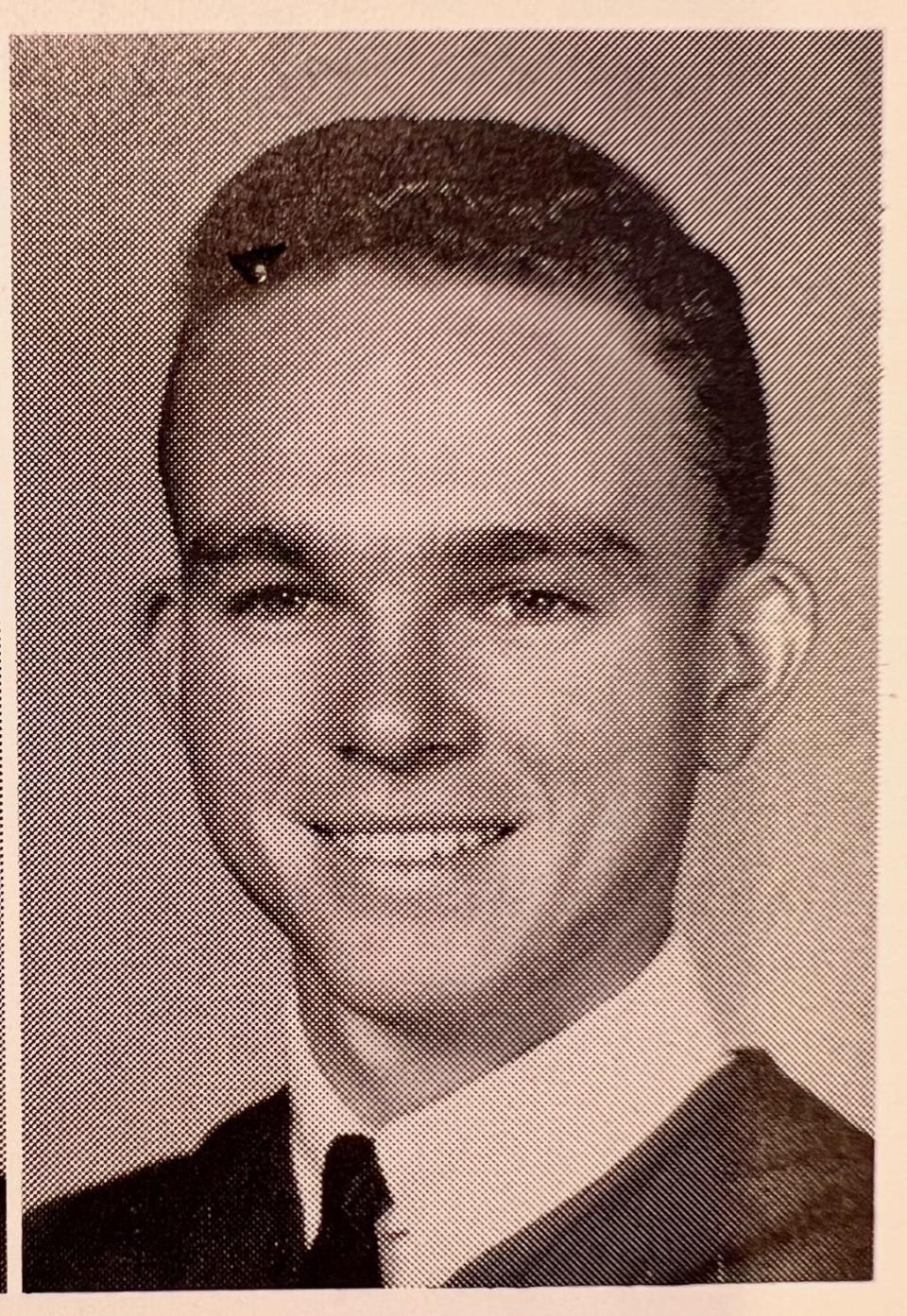

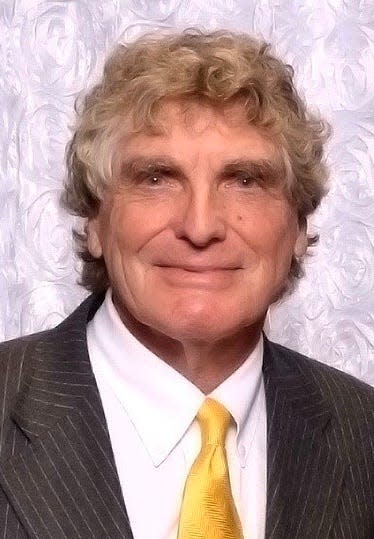

John Hulsey Hays

Johnny, who I knew through our mutual involvement in church and Boy Scouts as well as school, exuded leadership. He came from a wealthy family, lived in an elegant home, had his own car – a Plymouth Fury – and excelled at nearly everything, which in sum distinguished him from most kids our age.

Though advantageous circumstances may have given him a jumpstart in life, he displayed an unmistakable internal drive and ambition, and from an early age somehow managed to come across both as serenely humble and supremely confident.

In Troop 121, sponsored by First Presbyterian Church, Johnny was senior patrol leader while I was his understudy as junior patrol leader. Though two years younger and his acolyte, I felt a special pride of affinity when we became Eagle Scouts the same year.

Following graduation from West Point in 1965, John, as he was by then known, completed Airborne and Ranger schools – significant accomplishments in and of themselves – and married his college sweetheart, then took command of a unit in Germany “where he was recognized as the youngest and most junior tank commander in the cavalry,” according to a colleague’s recollection.

Deployed to Vietnam, he served under Col. George S. Patton Jr. and soon led troops into battle. Given everything that he had already accomplished – in concert with a tenacious professional drive and charismatic qualities of personality he possessed in abundance – his career path to flag rank was as clear as a bugle call. And in retrospect, as poignant.

The Distinguished Service Cross is the Army’s second highest decoration, just under the Medal of Honor and ahead of the Silver Star, which Johnny had already been awarded for meritorious conduct during an earlier armed engagement. All are earned at a cost, but the DSC he received was particularly expensive. He paid for it with his life. He was 25.

The citation reads in part: “Captain Hays distinguished himself by exceptionally valorous actions on 8 November 1968 while serving as the commander of an armored cavalry troop near An Loc. As Captain Hays was leading two platoons of his unit and a light tank section on a sweep through an area of dense rubber trees, a North Vietnamese Army force unleashed an intense barrage of small arms, automatic weapons and antitank rocket fire.

“He immediately led a charge toward the attackers, pushing them into another section of the rubber trees. The remaining enemy then joined with a still larger North Vietnamese Army element and began a determined defense. During the course of the fierce engagement, Captain Hays manned a machine gun and directed a tremendous volume of suppressive fire, while also coordinating his force through the use of hand and arm signals, which left him dangerously exposed. Suddenly his vehicle received a direct hit from an antitank rocket, knocking him to the ground.

“Although dazed, he ignored his injuries and, remounting the track, continued to fire the machine gun. When a group of North Vietnamese soldiers made a direct assault on his position, he killed two of them and scattered the rest. A few moments later his vehicle received another direct hit from an antitank rocket, mortally wounding him.”

Johnny left behind a widow, Leslie, and an infant daughter, Lauren, whom he never got the chance to hold, though he had doubtless often lingered over her photograph while anticipating his return to “the world,” as soldiers in Vietnam almost universally referred to home.

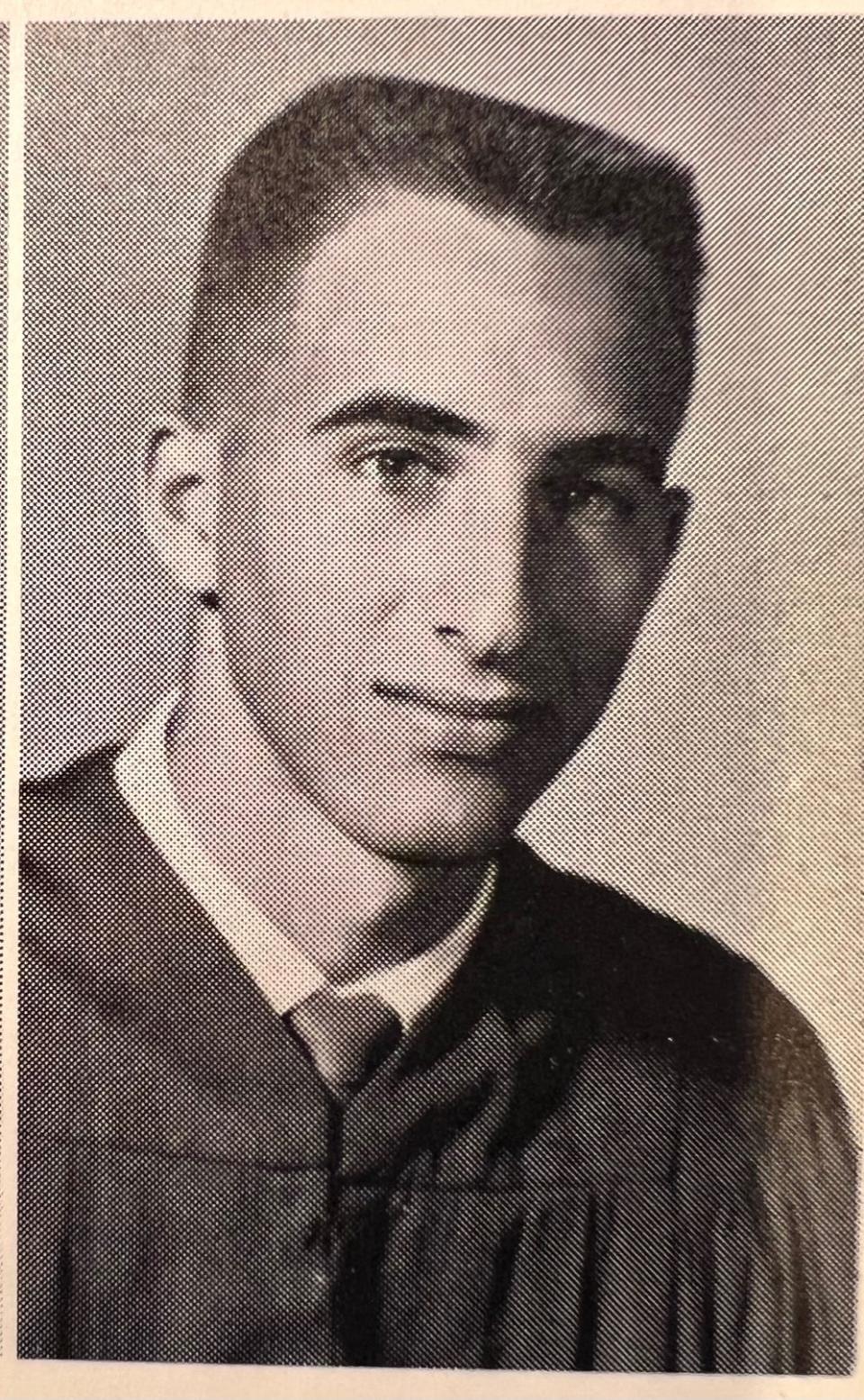

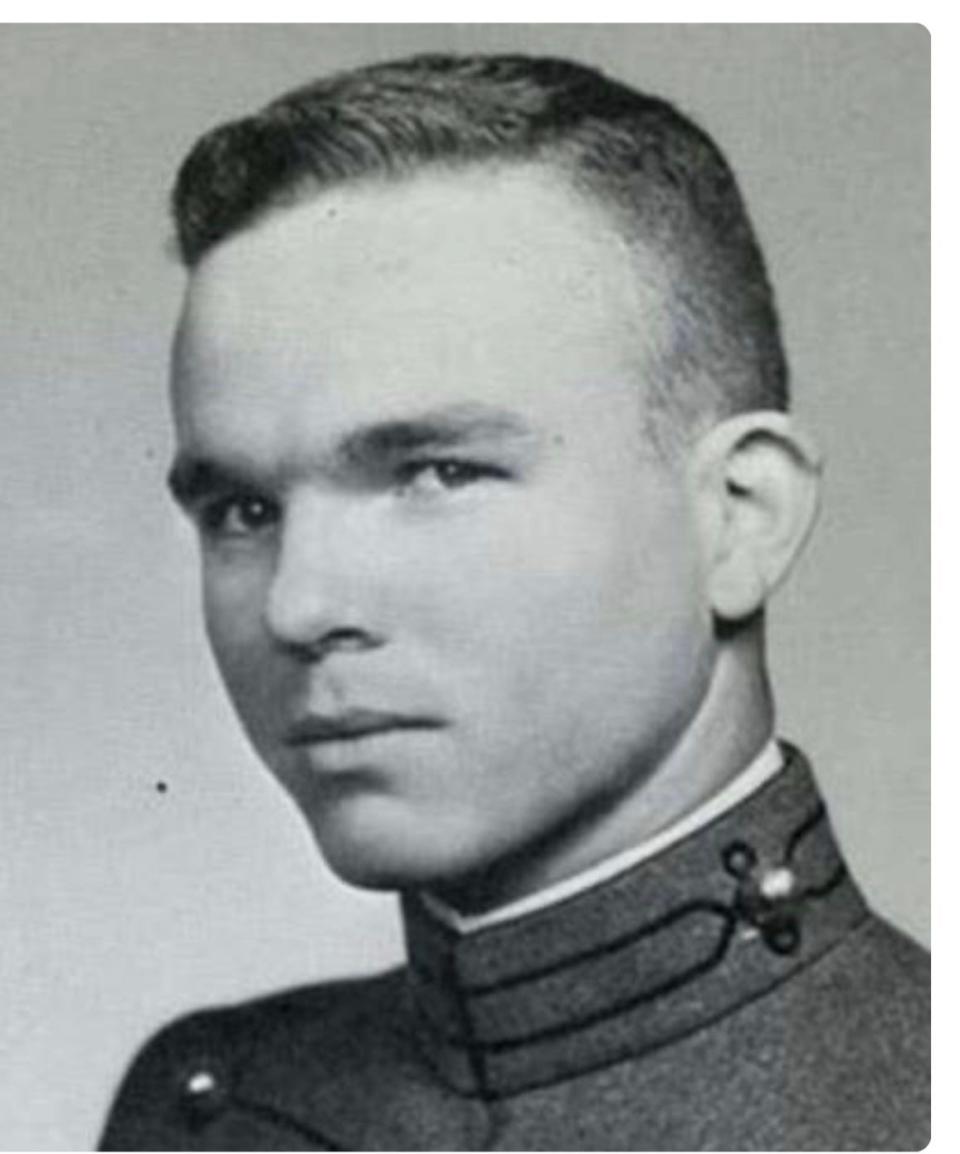

Richard Elmo Hood

Richard, a year older than me, graduated from high school in 1962. Though our respective maturity levels were considerably different than the small age gap between us might have suggested, he would nonetheless often invite me to double-date with him and his girlfriend on those happy occasions when someone agreed to go out with me – which for an upperclassman was an uncommon gesture.

Sometimes he also loaned me his car, another rare trait. But the ever-so-genial Richard had always been an uncommon soul and quietly marched to his own drumbeat. His independence of thought and action, evident early on, doubtless were among the attributes that impressed West Point.

He probably could have had his pick of service academies, but the Army held special allure. Both Richard’s grandfather and great-grandfather had been soldiers, and his own father was a sergeant in World War II who had taken Audie Murphy’s place when that legendary Medal of Honor winner was severely wounded in battle.

After graduating from West Point, Rich, as he had come to be called, completed both Ranger and Airborne schools and was almost immediately sent to Vietnam. He lasted less than a month. He was 22.

The dispassionate language of the citation for the Silver Star he was posthumously awarded can only begin to describe the unflinching courage Richard exhibited in the face of what must have been stark awareness of his own imminent death:

“On 22 June 1967, Lieutenant Hood's platoon was in a company movement deep in the jungles of Kontum province. Moving through dense vegetation, the platoon made contact with a North Vietnamese Army unit estimated to be of battalion size, and immediately sustained heavy casualties. Ordering his men to seek cover and set up a defensive perimeter, Lieutenant Hood moved through the intense incoming enemy automatic weapons fire to ensure that his platoon was intact.

"Through the ensuing seven-hour battle he personally directed the retaliatory fires of his platoon, repeatedly exposing himself to hostile small arms and automatic weapons fire. Although the unit was outnumbered and casualties were beginning to mount, Lieutenant Hood remained calm regardless of the fact that he lost communications almost immediately. Lieutenant Hood, realizing that the unit was completely surrounded and out of ammunition, continued to fight the enemy to the last with trip flares, constantly giving words of encouragement to his men."

Polk County's 80

Wars create scars seen and unseen and leave infinite possibilities forever unrealized. But it isn’t a stretch to imagine how Richard or Johnny or so many other dead soldiers, sailors, Air Force personnel and Marines with promising futures looming before them might have turned out – and how different this country might now be – had not the United States waded first by degrees, and then by a series of fatal immersions, into a historically grim swamp that literally sucked the life out of so much individual and national potential.

There was and is plenty of blame attributable to the top civilian and military leadership of the war, but the agonizing debacle was clearly not the fault of the enlisted and officer corps who did what their country asked of them – though many Vietnam veterans were subjected to unwarranted abuse and misplaced recrimination when they returned home.

More than 58,000 Americans lost their lives in Vietnam, while constituting the smaller portion of deaths in that beleaguered country. Hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese and more than a million North Vietnamese are believed to have perished during the period of U.S. engagement.

It is American sacrifices, though, that we note and honor on Memorial Day. Picnics and parades and speeches have their place, but it is more than appropriate – really, the very least we owe them – to give recognition to those who will never be able to take part in the celebrations, and to acknowledge the priceless gift of their “last full measure of devotion,” including the four score Polk County men who gave their lives in service to our country.

They are:

William Forman Abernathy, 28; James Robert Adams, 25; Kyle Ashcom Addair, 24; Herbert Marshall Allen, 22; Daniel Raymond Arnold, 21; Johnnie Harold Beasley, 18; Ronnie Hankins Bintliff, 19; Louis William Branch, 28; Guy Joseph Brungard, 35; Charles Frederick Buff, 28; Edwin Lewis Cahall, 37; Rudy Avon Carnley, 23; Richard Wilson Cole, 23; Idus James Conner, 19; Thomas Guy Curtis Jr., 27; Emmett Larue Davis, 18; William Terrell Davis, 21; Willie Gene Dyer, 25; Alton Lee Ellis, 20; Roy Scott Fischer, 18; John Norlee Flanigan, 39; James Folsom Fuqua, 21; Miguel Ramos Garcia, 21; Fred Richard Glover, 21; Stanley Maurice Godwin, 19; Jeremiah Green, 20; Eulas Fay Gregory, 24; Harlin Harris Jr., 19; John Hulsey Hays, 25; Alvin Gene Hill, 21; John Michael Hohman, 22; Richard Elmo Hood, 22; Donald Clement Hopewell, 18; James Laurence Howell, 22; Dale Martin Huston, 23; Tommy Hubert Ivey, 20; Seeber J. Kelly, 19; and Bruce Eugene Kline, 24.

Also Eli Whitney Knighton Jr., 18; Theodore Lamb, 25; Patrick Darren Lovell, 22; Dennis Dewain Manning, 19; Edward James Maslyn, 19; Edward Ulyses Masters, 19; Billie Ray McCall, 22; David Loren McGill, 19; Dalton Hubert McWaters, 18; Jackie Lee Melton, 20; Dennis Laco Morgan, 19; Eddie Lee Nails Jr., 20; Jesse Ernest Nixon, 29; Michael Barry O’Connor, 18; Gerald Everett Olson, 35; James Roy Pearson, 20; Thomas Wayne Peterson, 22; Jerry Newton Phillips, 39; Charles R. Pitts, 23; Walter Lee Redding, 21; Dorse Riggs, 26; Jerry Willie Ray Sanks, 21; John Andrew Schollard, 18; Wayne Gregory Scrimshaw, 22; Roy Henry Sheffield, 20; Maurice Leo Sirois, 30; James William Spivey, 20; Thomas Earl Springfield, 18; Paul Francis Stedman, 19; Peter Joseph Stewart, 46; Raymond Wilson Teal, 26; Kenneth Ray Temples, 21; William Darrell Thompson, 20; John M. Vollmerhausen Jr., 18; Isum Merrill Walker, 20; James Harrell Waller, 22; Delbert Ellis Weber, 41; Donald Frederick Weinman, 23; Terry Welch, 20; Harry Ray White Jr., 18; Phillip W. Williams, 20; and Donald Coles Woodruff, 28.

Thomas R. Oldt served in the U.S. Navy during the Vietnam War. He may be reached at tom@troldt.com.

This article originally appeared on The Ledger: Winter Haven's John Hays and Rich Hood died in Vietnam 17 months apart