Children of the cartel: CJNG members describe what led them to a life in organized crime

Warning: This story contains graphic descriptions that may not be suitable for all audiences.

MORELIA, Mexico ― “I had to burn some guys alive; that was my first task,” the 18-year-old said with some excitement in his voice, recalling his first assignment in a Mexican cartel.

“We were chilling out, and two hours later they brought them. We tied them up and sprayed them in gasoline and then fire; it smelled terrible,” he recounted while eating tacos and drinking Coke in downtown Morelia.

He said he was 15 when he was formally hired by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG). He said he had no other path, and started as a “halcón,” or street-level cartel informants. Then he began to advance, and now he’s a full-time hitman for one of the most brutal cartels in the world.

“I enjoy killing. Sometimes, I even do it for fun,” he said, expressing no regrets over the lives he has taken.

“I’d rather not count,” he said of the total.

Born and raised in Morelia, the capital of Michoacán state, he said he doesn’t have many childhood memories – except for the cancer death of his mother, which he said makes him feel sad.

He spoke on the condition his name not be shared. The Courier Journal granted anonymity to some of the sources in this story, so they could freely speak to their experiences and what led them to life in a cartel.

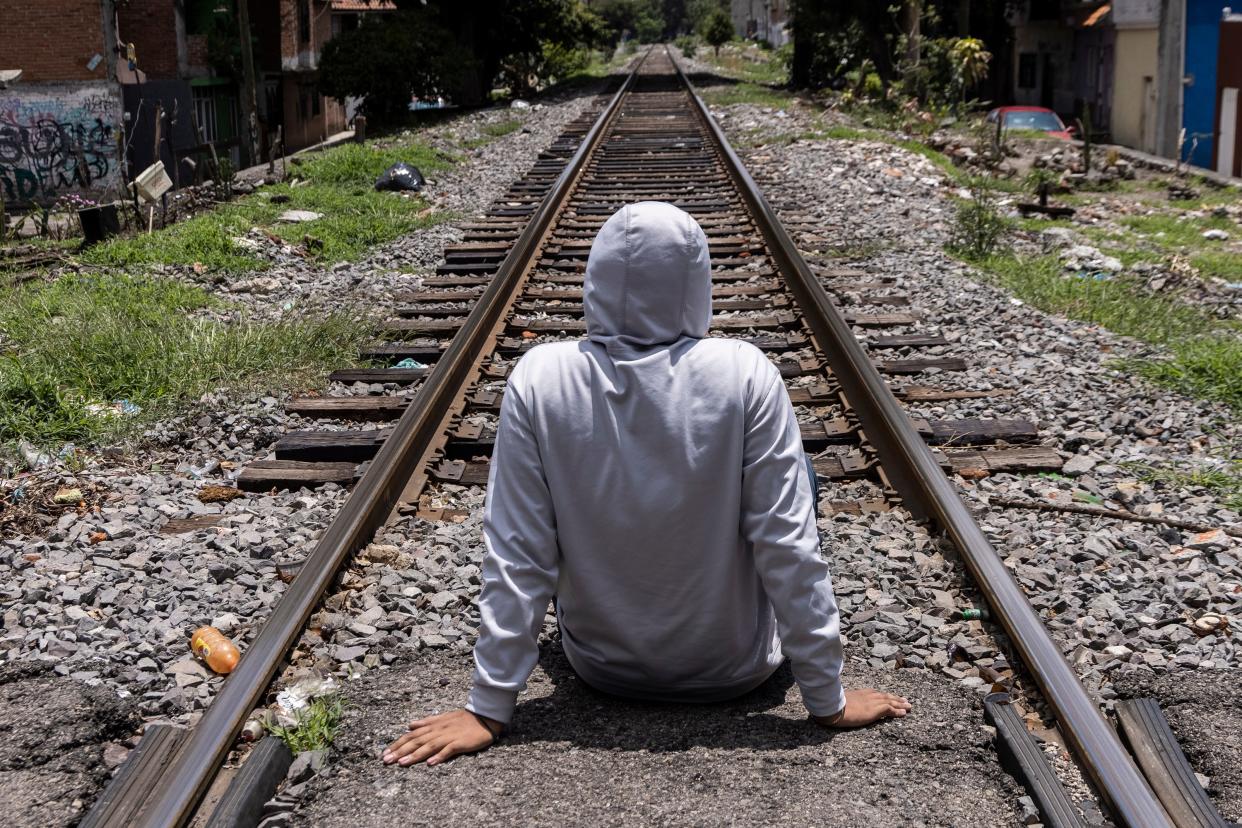

His story reflects how organized crime ends up being the only option for thousands of children in marginalized areas of rural Mexico.

The Network for Children’s Rights in Mexico estimates about 35,000 youths have been recruited by organized crime in the country, and about 400,000 more are currently at risk of being recruited.

The statistic is a constantly moving target, experts say.

“We're talking about an annual estimate because adolescents turn 18 and can no longer be considered in that statistic,” said Juan Martin Pérez García, the coordinator of children’s rights group Tejiendo Redes Infancia in Latin America and the Caribbean.

“But new (children) are entering, and that has also led us to raise with great pain the recognition that adolescents who are victims of recruitment are disposable,” Pérez García said.

‘Aspiration is never lost’

While Mexico has seen recent improvements in its poverty rates, the latest figures from The National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy show nearly half ― 43.5% ― of the population living in poverty in 2022.

Mexico-based experts say inequality, lack of opportunities, poverty and other factors fuel cartel numbers in rural Mexico.

“The state is not capable of generating conditions of well-being, and the young persons, even if they come from an impoverished society, from a fragmented family, they aspire, because aspiration is never lost -- the human being always aspires,” said Ruben Ramirez, a professor and researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

“Let’s be honest, to make money is really hard. I can’t say how much I make, but it’s definitely more than what a doctor does here in Mexico,” the young CJNG member said.

“In five years, I see myself as Pablo Escobar,” he said with a laugh, referring to the notorious Colombian drug lord.

Drug cartels have deeply penetrated Mexican society, particularly in rural areas, Ramirez said. They get involved in elections and donate food and money to local families.

In many cases, they have filled the blank spaces that the state has left, he said.

And the children are watching.

“For many years in this process of socialization, the children manifest that in their adult life. They would like to be hitmen, they would like to be members of the cartels because they are observing and analyzing it as a possibility,” Ramirez said.

“A possibility to aspire to something illegally because the economic and political system does not offer possibilities. In Michoacán, the main topic in parties and meetings is the drug war, so it’s what these kids see in their life since they were born.”

The young CJNG member said he got involved “just to do something, to have fun.”

He’s aware that cartel life is often short, but “the only person that would make me get out of this would be my mom ― and she is dead.”

‘You just don’t have any other choice’

“Sometimes there is forced recruitment, in specific cases, but we usually don’t mess with the innocents,” a CJNG chief commander told The Courier Journal.

The now 30-year-old man, who also spoke on the condition of anonymity, started running errands for the Familia Michoacána cartel when he was 10.

In his youth, he had dreams of a profession, a house, a family and a lot of money, but his environment worked to put some of those things out of reach.

Instead, he decided to join the cartel to start working on his dreams.

“The need also forces you. You just don’t have any other choice than to join and work hard,” he said.

There is a debate among scholars in Mexico regarding how some young men join the cartel.

Some argue it is not possible to “voluntarily” join a cartel when it’s the only option.

“There is no possibility of a voluntary entry when they have no other way of surviving or when they even have to enter to protect their life or that of their family,” said Pérez García, the coordinator of the children’s rights group.

It can be literally necessary to survive in the cartel territories, Pérez García said, and the state has practically no preventive action at all.

Forced recruitment into organized crime is not unheard of in Mexico. Local media have documented cases where job listings in newspapers or online result in forced cartel labor for those who show up to apply.

But for those who see no other route ― a minor or otherwise ― it’s not that difficult to join.

“It’s not hidden. People know who the leaders are, so it’s not difficult to approach them and ask for a job,” Ramirez said.

Meanwhile, state and social programs to head off this pathway remain scarce.

“The truth and only truth is that if they gave me another option, I wouldn’t do it because I can't do another option,” the CJNG commander said. “It's all here. I have many enemies, so if I leave, I'll be unprotected and will be dead immediately.”

A country at war?

Child recruitment is not a crime in Mexico. Advocates have been fighting to make it one for the past decade.

Pérez García said the government has refused to classify it as such, as requested by the Committee on the Rights of the Child at the United Nations in 2015, because it would imply there is a war in Mexico.

"Beyond whether there are 30,000 or 100,000 recruited children, the state continues to fail because there is no way to protect them as long as the crime is not classified in the Penal Code, as long as there are no programs and budget to attend to the victims," he said.

“We talk about deaths, missing persons, displaced persons, extortion, and recruitment. Mexico is a country at war, although it is not recognized as such,” Pérez García said.

In Mexico, more than 110,000 people are believed to be missing, many in the wake of government efforts to crack down on drug cartels. The government reports 3,726 people age 17 and younger went missing between January and October 2021.

Without legislation, the responsibility for child recruitment falls just as much on the government as the cartels, Ramirez and other experts agreed.

“Organized crime arose because the state failed. These criminal groups appeared because the state was unable to fill those spaces…,” he said.

Meanwhile, in Michoacán, the CJNG commander said he misses his brother and works every day to avenge his death.

“I miss him. I can’t stop thinking about how they killed him.”

After he killed a prominent man in a town in Michoacán, a commando entered his house days later and took his younger brother.

“I never knew how he died, but I’m sure it was in the worst way. He was not involved in this.

“He was only 14 years old.”

Cristopher Rogel Blanquet is a photojournalist based in Mexico City. Karol Suárez is a Venezuela-born journalist based in Mexico City. They are contributors to The Courier Journal. Follow Suárez on Twitter at @KarolSuarez_.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: CJNG members describe what led them to a life with the Mexican cartel