Children survive alone for years, against all odds | DON NOBLE

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 2010, Edward O. Wilson, arguably the most famous naturalist of our time, had published 24 books of nonfiction, two of which won the Pulitzer Prize, all exploring and explaining the worlds of super-organisms like insect societies, and our own human behavior in his controversial “Sociobiology: The New Synthesis” (1975).

Then Wilson surprised his readers by publishing a novel, “Anthill.” When asked, he responded that there would be some people who would never read a book like “Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge,” but they might read a story, and Wilson could convey his wisdom about the natural world in novel form.

Janisse Ray is an award-winning nature writer with 11 books. The most recent, “Wild Spectacle: Seeking Wonders in a World Beyond Humans,” won the Donald L. Jordan Prize for literary excellence, which carried a $10,000 cash prize.

Now Janisse Ray has written her first novel, and it is indeed set in nature, but has a much different tone.

“The Woods of Fannin County” is based on an actual story, which makes me sad, because it is a very rough story indeed. Ray has extensively interviewed the principal players in this drama and this powerful story is accurate, down to the details.

In the late summer of 1945, Ruby Woods took her eight children, from age 10 to a nursing infant, to a remote tumbledown shack in the mountains of northeastern-most Georgia and basically abandoned them there.

Ruby visited rarely, sometimes with four months in between visits, usually bringing corn to be cooked as hominy and very little else. Is their mother evil or has she lost her mind?

The children are on their own as surely as if they were on an island. They are starving and keep themselves alive by foraging. Over time they learn to find, prepare and eat wild apples, pears, black walnuts, hickory nuts, poke salat, berries, grapes. The oldest, Bobby, learns to kill squirrels with a slingshot.

The natural world in which the children live never loses its beauty, but is dangerous — copperhead snakes slither out of the fireplace — and gives up its sustenance only with herculean effort.

The first winter, the baby almost freezes to death. All eight sleep together under a pile of rags to keep warm.

We learn that Red, the children’s father, has deserted Ruby, and she cannot stand the sight of his offspring.

She is cruel to them all, but on her rare visits she actually tortures Phyllis, a redhead who looks the most like her father.

(In the animal world, a female chimpanzee, a new bride, a stepmother, so to speak, might kill the offspring of her mate from his previous mating, to increase the chance of survival of HER offspring.

Human stepmothers, although famously wicked in fairy tales, do not go that far. In “Cinderella,” the wicked stepmother makes Cinderella a servant and advances the chances of her own daughters.

Ruby endangers the lives of her own offspring.)

The children are on their own, but we learn they don’t really need to be.

They learn that their grandparents live nearby, and know about their plight, but will not help except for a small amount of credit for beans and rice at the general store.

Many, down in nearby Morganton, Georgia, including the local preacher, also know, but do not help. It is a fantastically extreme case of “country people not wanting to “get involved.” This is carrying the rural virtue of minding your own business to a callous, I think criminal, extreme.

“It takes a village,” they say, but in this case the village does not show up.

Ray chooses to tell the story mainly through Bobby, the oldest, who deserves most of the credit for their survival, creating a “shaky civilization” of their own.

And survive they do, miraculously, for four years, before they are taken to an orphanage where they live until they age out. They were damaged by their experience, suffered a kind of civilian post-traumatic stress disorder, but they did go on to live relatively happy lives. Otherwise, this painful, distressing story would have been too bleak, even though it was so well told I read it compulsively, couldn’t look away, like the proverbial train wreck. I was greatly relieved when the children made it through.

When I was a college freshman, my Psychology 101 professor told us there was no such thing as instinct in humans. Instinct had to be species-wide, he said, no exceptions, and some human mothers abandoned their infants – ergo, no instinct.

It was a time of nurture only. B. F. Skinner’s “box” came into vogue.

E. O. Wilson led us in a different direction with “Sociobiology” and other works, insisting that genetics played a part in human behavior. Even altruism, self-sacrifice, which seems contrary to individual “survival of the fittest,” had its place in the success of the family, the tribe.

Human life was a combination of nature and nurture.

I agree with Wilson, of course, and in this story the children do all cooperate beautifully to keep themselves alive, but one will never see a better example of the failure of mother love than in “The Woods of Fannin County.”

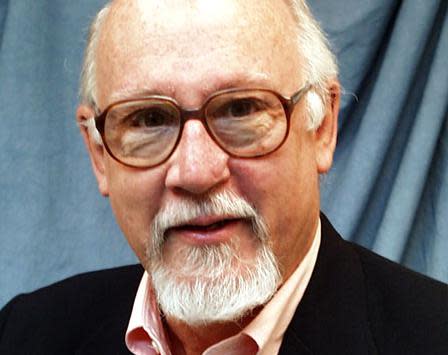

Don Noble’s newest book is Alabama Noir, a collection of original stories by Winston Groom, Ace Atkins, Carolyn Haines, Brad Watson, and eleven other Alabama authors.

“The Woods of Fannin County: Based on a True Story”

Author: Janisse Ray

Publisher: Janisse Ray

Pages: 207

Price: $19.99 (Paper)

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: Children survive alone for years, against all odds | DON NOBLE