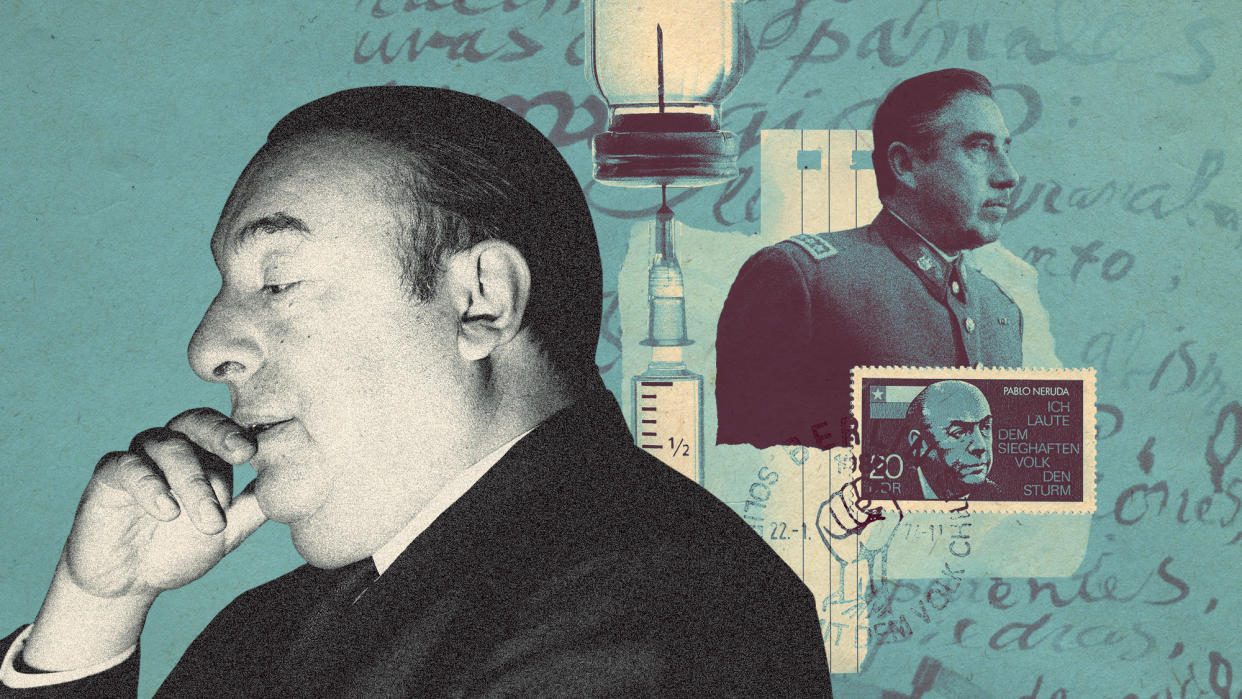

Chile revisits the mysterious death of poet Pablo Neruda

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Chile has reopened a long-running investigation into the death of Pablo Neruda, its Nobel prize-winning poet and former communist politician.

For more than 50 years, Neruda's death has been "a mystery", said The Times. His family and the country's Communist Party have "long argued that he was assassinated", while the "official version" is that Neruda died from prostate cancer and malnutrition aged 69 in September 1973 – just 12 days after General Augusto Pinochet "overthrew Neruda's friend, President Allende, in a coup".

For more than a decade, experts in Canada, Denmark and Chile "have pored over the poet's remains in a bid to establish what killed him, but have been unable to provide a definitive answer", said the BBC. Last week an appeals court unanimously voted that an investigation that ended last year "has not been exhausted as there are precise procedures that can be carried out to clarify the facts".

What happened to Neruda?

Best known for his lyrical love poetry, Neruda became increasingly political through his life. In 1936, he was radicalised towards communism by the Spanish Civil War and the assassination of his close friend and famed Spanish poet, Federico García Lorca.

By the time he died, he was known as Chile's most important intellectual, a friend of the democratically elected leader Salvador Allende and a vocal opponent of Pinochet.

Neruda planned to go into exile in Mexico after the US-backed coup of 1973, as a strong voice of opposition – but one day before his departure, the poet (who was already suffering from prostate cancer) fell ill, was taken to hospital in Santiago and died just days later. Pinochet's regime would go on to kill about "3,200 left-wing activists and other suspected opponents", said The Times.

Suspicions that Neruda's death "had nothing to do with his disease" have lingered in Chile since Pinochet's military dictatorship ended and the country returned to democracy in 1990, said Remezcla.

In 2011, Neruda's driver and personal assistant Manuel Araya claimed the poet had been given a deadly injection of poison by agents of Pinochet's junta, leading the Chilean government to investigate his death.

Neruda's body was exhumed in 2013, and two years later the government admitted that it was "highly probable that a third party" was responsible for his death, said Sky News.

In 2017, a group of scientists from McMaster University in Toronto and the University of Copenhagen concluded that Neruda had not died of cancer. Last year, they delivered their long-awaited verdict: they had found "a great quantity" of Clostridium botulinum in one of Neruda's teeth. "The botulism strain produces one of the deadliest toxins known to mankind, botulinum, and is known to have been used as a biological weapon in several countries," the scientists said.

Although they stressed there was no proof that the toxin had killed Neruda, their report led Neruda's family to call for judges to reopen the case. "We need clarity," Neruda's nephew Rodolfo Reyes told the BBC last year. A judge rejected the request, but the decision has now been overturned.

A divisive legacy

While the cause of his death remains a mystery, Neruda's legacy has become increasingly divisive.

"Radical feminist groups" fiercely opposed a 2018 campaign to rename Santiago's international airport after him, said MercoPress. They argued that, at the height of the MeToo movement, "it portrayed a bad image of the country abroad", because Neruda "abandoned" his seriously ill daughter and, in his memoirs, described raping a maid in Sri Lanka.

While Chile is "at war" over the relevance of Neruda, the country remains "deeply polarized" over its recent history, said The New Yorker. Last year, around the 50th anniversary of the coup that brought Pinochet to power, Chileans rejected an attempt to write a new constitution to replace the "heavily amended" one adopted by Pinochet's regime – for the second time.

In September 2022, they rejected a "left-wing reform" in a landslide vote; in December, a right-wing alternative was "soundly rejected". The conundrum underscores the difficulty of coming to agreements in modern Chile, said the magazine.

Another constitution vote seems "highly unlikely" until at least 2025 while the leftist president President Gabriel Boric focuses on reforms, said Al Jazeera.

But as to what really happened to Neruda all those years ago, Chileans may never agree on an answer.