China spread disinformation videos on Uyghur Muslims two years ago. YouTube let them stay up.

In the YouTube video, Ipargul Obul smiles shyly in bright red lipstick, her hair carefully coiffed.

“Under the influence of extremist ideas, I used to think that women must wear long dresses and cover their faces,” Obul says. “But, after receiving training here, I’ve realized that women are beautiful and will look even better with makeup.”

That training, she says, came at the Hotan County Vocational Education and Training Center, a detention facility for Uyghurs, most of them – like Obul – Muslim. In the video, she says she was taught to be a hairdresser there.

Many other Uyghur men and women have relayed a far different story, telling reporters, researchers and government representatives that they were held against their will at Hotan and other centers by the Chinese government, forced to work in factories and perform manual labor.

In its annual State Department human rights report, the Biden administration accused China of “genocide and crimes against humanity,” estimating the Chinese had detained 1 million Uyghurs and other minorities.

Chilling evidence: The U.S. says China is committing genocide against the Uyghurs

Obul is featured in a five-part YouTube series with Chinese government connections, provided to USA TODAY by the research collective Bellingcat. Experts said it is unethical for YouTube to allow such propaganda on its platform, saying it promotes the abuse of Uyghurs and subjects viewers to false information.

YouTube said the videos do not violate its community guidelines. In a statement, the company explained that false information alone is not enough to warrant removal of videos from its site unless it includes hate speech or harassment or incites violence. However, after USA TODAY sought comment from the company running the YouTube channel, Nikita Asia, it took the videos down late last week.

“From today’s perspective the reporting about the situation of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang in these 5 videos is indeed not balanced enough and possibly transports the opinion of the Chinese government,” Nikita Asia said in an email. “Today, we would not choose them anymore for publication and have already removed this content from the channel after your notice.”

Since 2014, Nikita Asia has partnered with Chinese state-sponsored media to distribute its content to a Western audience on YouTube. It runs the channel China Live, which posted the series shot at two detention centers. That channel has more than 170,000 subscribers on YouTube, and the video series was viewed tens of thousands of times.

University of Colorado professor Darren Byler, a Xinjiang expert, disagrees with YouTube’s assessment that the videos do not promote violence.

Along with other experts interviewed, Byler describes them as an obvious attempt to counter the human rights abuses in Xinjiang, a territory in northwest China that is home to several ethnic minority groups, including the Uyghurs. The Silk Road trade route linking China to the Middle East once traversed it.

“By allowing (the video series) to circulate on YouTube, it's promoting a kind of state violence that, by not naming it as such, is allowing it to circulate as normal news,” Byler said.

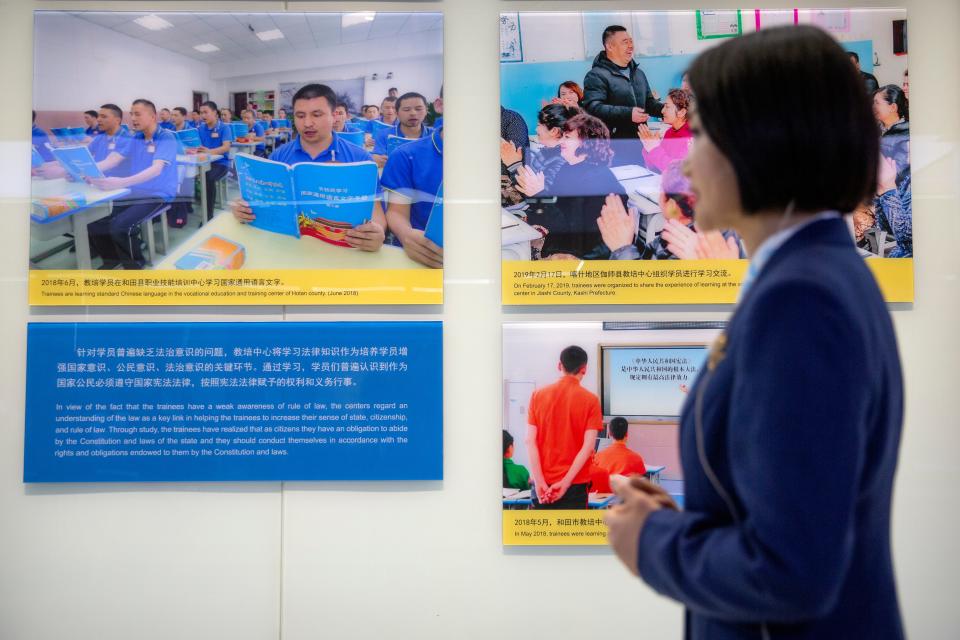

China has denied many of the accusations about its treatment of Uyghurs but also defends the centers as necessary reeducation camps to combat extremism and terrorism.

The video series includes interviews with almost a dozen Uyghur men and women who claim the camps have improved their lives, making them more beautiful, kind and intelligent. One key focus is denouncing traditional Muslim practices, describing veils worn over hair or face as “religious extremism” and Muslim religious teachers as “illegal religious personnel.”

In addition to Obul, the series features other Uyghur women assimilating to Chinese standards of beauty by using makeup and striving for lighter skin and slimmer physiques.

The camps featured, Hotan County Vocational Education and Training Center and Moyu County Vocational Center, are part of a sprawling network across Xinjiang. Chinese media refers to the two as having “labor-intensive programs” to “promote employment,” which Byler described as coded language.

“I would say undoubtedly that there’s forced labor associated with it,” he said.

YouTube fails to monitor state-sponsored media

YouTube promised in 2018 to label channels and videos that are state-funded. The following year, ProPublica found that it had failed to identify 50 channels funded by countries including Russia, Iran and the United States.

More: YouTube to label state-funded news videos in effort to provide transparency

YouTube did not label the Uyghur series, either, until it was contacted by USA TODAY. Although YouTube spokeswoman Elena Hernandez told USA TODAY that the company’s “Trust and Safety Teams did not find evidence of this channel being part of a coordinated influence operation,” it opted to add a label to the series on June 3 – a day before it was taken down by Nikita Asia.

Both YouTube and Google are blocked in China, meaning the YouTube videos are not available to Chinese audiences. But the series also aired in China, according to Nikita Asia.

A prominent Chinese government official also promoted the YouTube series online. The deputy director of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs Information Department Lijian Zhao tweeted the link and title to all five videos from the series on April 18, 2019 along with other Uyghur propaganda videos on YouTube.

YouTube and its parent company, Google, already have faced criticism for their dealings with the Chinese government. YouTube recently was discovered deleting comments critical of the Chinese Communist Party, and Google was developing a Chinese search engine compatible with state surveillance until it called off the project in 2019 amid public outcry.

In addition, YouTube has benefited financially from Chinese state media ads on its platforms, as have Facebook and Twitter.

According to Xinjiang expert Adrian Zenz, tech companies running these ads are complicit in China’s disinformation campaigns, including those related to Uyghur detention.

“Western companies are clearly making money off a trusted denialism,” said Zenz, a senior fellow in China studies at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, a human rights nonprofit authorized by Congress in 1993.

Zenz has become a target of the Chinese Communist Party, which in a March news conference called him “a goon fed by anti-China forces” and a “sinister partner of … terrorist organizations.”

An attempt to reframe the narrative

For most of the U.S. population, the video series would not outweigh reporting from mainstream media outlets. But for some Chinese Americans, it could be a different story, according to Dolkun Isa, who is president of the World Uyghur Congress and has family members in the detention centers.

Recent immigrants, Isa said, may still accept the Chinese Communist Party’s rhetoric about Uyghur detention even though, unlike mainland Chinese citizens, they also have exposure to Western media refuting those narratives.

“Inside, the Chinese people didn't understand what was going on because it's all brainwashing, and they really don't have an opportunity to live in truth,” Isa said. “But, as we've seen, China's diaspora is divided into parts, and even the good parts support China's authoritarianism.”

The Uyghur video series is a small part of a larger influence campaign by the Chinese government to change the international narrative on the detention centers, experts told USA TODAY.

Byler likened them to propaganda used in Nazi Germany to counter narratives of the Holocaust.

“This is like a Potemkin village (in) the 1940s in Germany or the Czech Republic,” Byler said. “The Red Cross was shown camps, to, where Jewish people and others seemed to be working happily in a factory. So, that's how this should be viewed.”

According to Zenz, the 2019 video series was a harbinger of today’s more complex information campaign. Since then, the Chinese Communist Party has co-opted multiple English-language media outlets, such as the Global Times, Zenz said, and coordinated social media activity to make disinformation easily accessible to Western audiences.

Contributing: Jessica Guynn, USA TODAY; Pieter van Huis, Bellingcat

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: YouTube hosted China disinformation campaign about Uyghur Muslims