Yosemite's old laundry facilities are being converted to shine light on Chinese labor

In the spring of 1875, about 300 Chinese workers accomplished a monumental feat: They built a 23-mile road in Yosemite National Park in about four and a half months.

Construction began in December 1874 with a crew of 50 people who worked through snowy conditions to build a road that gained 3,000 feet in elevation. Once completed, the road linked an area close to the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias to Yosemite Valley.

It’s one of four major roads that lead into one of America’s most best-known national parks. Chinese immigrants were the primary workers on two of them but helped build all four.

They were among hundreds of Chinese immigrants who contributed to the development of Yosemite National Park. Their history in the park has remained widely unknown, which has prompted advocates over the last several years to launch efforts to raise awareness about their role.

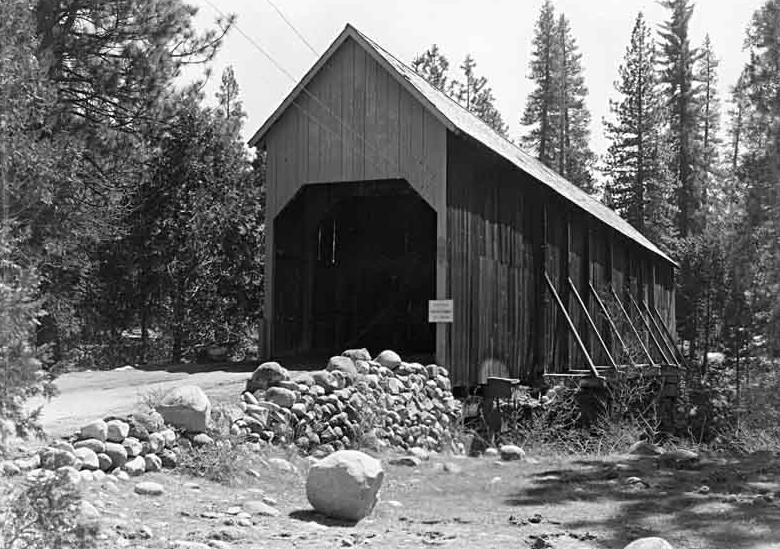

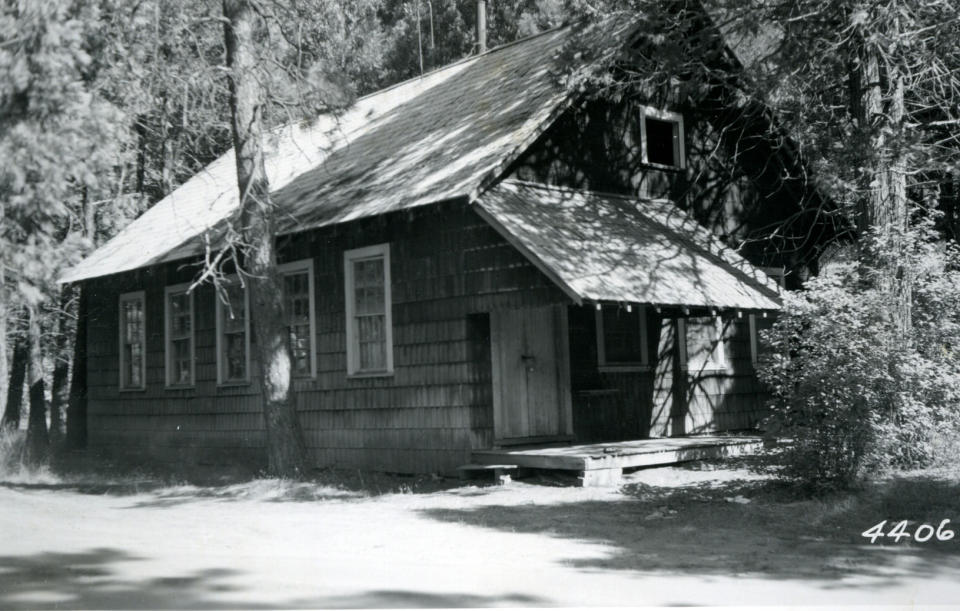

One of those efforts is the restoration of a Chinese laundry that opened to the public Friday. The building will be dedicated to telling the story of Chinese immigrant workers in Yosemite National Park, including the stories of those who built park roads.

Sabrina Diaz, who was chief of interpretation and education at Yosemite National Park and is now deputy superintendent of Everglades and Dry Tortugas National Parks, initiated the idea of restoring the building after learning in 2017 that it was being used for storage. She told NBC Asian America in an email that it is the last remaining laundry building from Yosemite’s early days.

“I felt like we were not preserving their part of our shared history in a way that would make them or us proud,” she said.

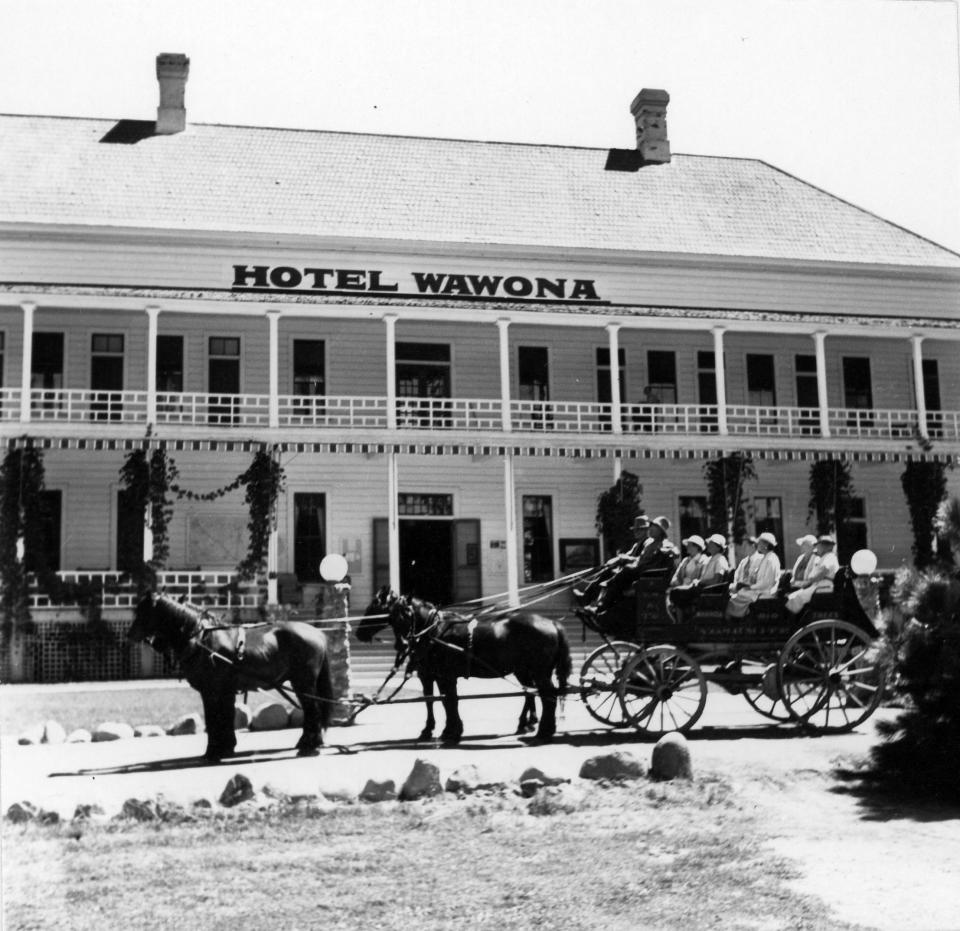

The building will showcase various parts of Yosemite’s Chinese history through text and photos projected onto walls. Parts of the history that will be highlighted are workers who built major roads, including Tioga Road, north of Yosemite Valley; the contributions of Tie Sing, a cook, to the establishment of Yosemite National Park and the National Park Service; the history of Ah You, who served as head chef of the Wawona Hotel in California for 47 years; and the contributions of Chinese who worked in Yosemite’s hotels.

Yenyen Chan, a Yosemite Park ranger who has conducted extensive research on the history of Chinese in Yosemite, wrote in the journal The George Wright Forum that many Chinese were hired at Yosemite hotels because of their work ethic and culinary skills.

Beth Lew-Williams, an associate professor of history at Princeton, said the work ethic of Chinese immigrants who came to the United States was directly influenced by the conditions they worked under and the choices they were forced to make. Men often immigrated without women and children, which made work a central part of their lives. Domestic demands were different without their families, which affected their leisure time, Lew-Williams added. Workers also faced economic pressure to send part of their earnings to support their families in China.

These conditions led them to become stereotyped as industrious and servile, which affected how employers treated them.

Chan told NBC Asian America in 2018 that Sing played an important role in cooking meals for a two-week wilderness expedition in 1915 that was intended to convince business and cultural leaders of the importance of a national park system.

“It wasn’t a minor role,” Chan said. “I think they were amazed that he could make meals that were basically multicourse meals in the backcountry.”

Sing’s work appears to have been appreciated. Members of the group that embarked on the expedition recorded his meals in their notes — including how Sing was able to put together a “fabulous dinner” even though a supply mule carrying “delicacies” like cantaloupe and fresh lemonade had wandered off. The following year, the federal government established the National Park Service.

Lew-Williams said there has been a general pattern of Chinese immigrants from the 19th century being forgotten in the larger history of the American West. Part of that stems from the fact that many Chinese who came to the country were transient and illiterate, that the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 has left the country with few descendants from that period of time, and that history has traditionally been Eurocentric.

“It doesn’t mean that individual people at the parks system were attempting to keep Chinese out of this history,” she said. “But I think it’s more the choices they were making about how they portrayed the history of their park reflected their own biases over time over what should be celebrated and remembered.”

She also said that the contributions of Chinese immigrants to the country, including national parks and the Transcontinental Railroad, have long been recognized in the Chinese American community, by Asian American organizations and activists. The surge of anti-Asian hate during the pandemic appears to have drawn broader American attention to this history, she said.

Jack Shu, who helped to review information that will be presented in the laundry building, has been involved in efforts to raise awareness about Chinese history in the United States. In 2013 he established an annual Yosemite-Sing Peak Pilgrimage to honor Chinese who helped develop Yosemite National Park. Six years later he organized a hike along a 10-mile stretch of the first transcontinental railroad that Chinese and Irish workers laid down in a single day 150 years earlier -- a record-breaking feat.

He told NBC Asian America in 2018 that he was saddened to learn that Sing’s story wasn’t widely known. He had worked in California’s Department of Parks and Recreation for 29 years and had worked with the National Park Service during that time, and felt it was a missed opportunity for the agency to share more about Chinese history.

“Even though it’s done a good job of preserving this story, they’re far from changing the narrative for the general public,” he said.

Shu said in September that he was elated when he first learned about the laundry building in 2012 because it’s a physical structure that people can point to and experience, as opposed to a site where something previously existed. In addition to information that will be projected on the walls, he hopes the building will be able to exhibit some irons that Chinese workers used -- ones that had to be heated up on a stove or were loaded with hot coals.

“These things weigh about 4 pounds, much heavier than present electric irons,” Shu said. “So we give a visitor an iron and say, ‘Hey, imagine using this to iron over many, many sheets.’ That’s how people remember things, and that’s what having a facility like this helps provide. So when you hear of the Chinese working in the service industry and helping in the hotel, it sticks because your arm got sore.”

A crucial contribution that made restoration of the building possible came from Franklin and Sandra Yee, Sacramento residents who donated $100,000 in commemoration of Sandra Yee’s parents’ love for Yosemite.

In a time of rising anti-Asian hate, Shu said he hopes that the laundry building can serve as part of a solution to the problem.

“I hope we can contribute in that way, that when someone knows some of this history, they know that the Chinese are not foreign -- that they are part of the American history,” Shu said.

CORRECTION (Oct. 11, 2021, 1 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misstated a highlight of the laundry exhibit. The history of the Buffalo Soldiers is part of an adjacent exhibit, not the one featuring an old Chinese laundry. The reference has been deleted from the article.