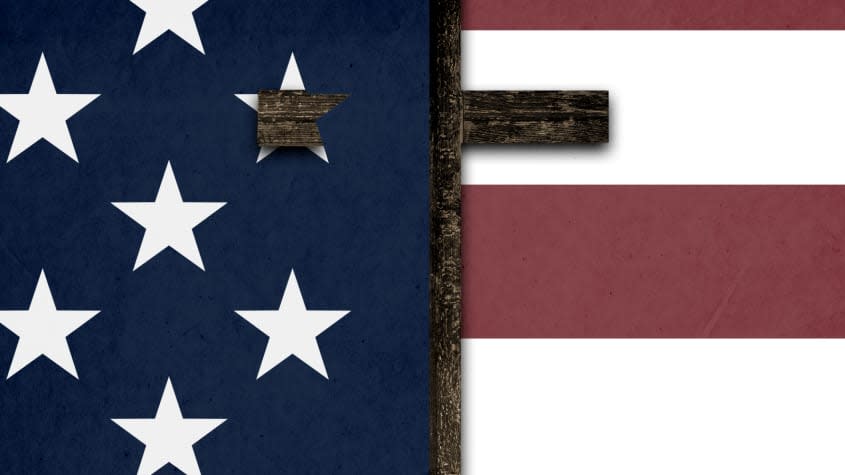

Christian nationalism is real. The way you talk about it might make things worse.

What is Christian nationalism? Unless you're a devoted student of religion and politics, you'd be forgiven for wondering.

The concept has circulated for decades in scholarly circles, where it was more often used in an international context than applied to the United States. But since 2016, it's become a popular term of art for Christian conservative politics. Georgetown international affairs professor Paul D. Miller defines Christian nationalism as "the belief that the American nation is defined by Christianity, and that the government should take active steps to keep it that way." Sociologists Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry use six criteria, including belief that the federal government should declare the U.S. a Christian nation and that American success is "part of God's plan."

It's easy to find criticisms of Christian nationalism, which dominate both academic and popular discussions of the subject. It's far more difficult to locate advocates, at least under that name. Rather than encouraging substantive analysis of specific opinions or proposals, the label functions as a pre-emptive dismissal. To describe something "Christian nationalism" is inevitably to reject it.

That rejection is too quick, though. It's possible to worry about specific kinds of political enthusiasm without dismissing all religious interpretation of American history or purpose. "Christian nationalism" is simply too broad identify the real problem with some brands of right-wing politics — as shown by the fact that a majority of Americans meet at least one of Whitehead and Perry's criteria. Christian nationalism, in the scholarly sense, certainly exists in this country. But in its popular incarnation, the phrase often confuses more than it clarifies — and its overuse may undermine one of our best defenses against the real thing.

It was certainly used in the dismissive sense last week. Commenting on Archbishop José H. Gomez's remarks at a meeting of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, religion journalist Jack Jenkins wondered on Twitter whether Gomez "just dropped Christian nationalism into his opening address, suggesting America historically held a 'biblical worldview' and 'Judeo-Christian heritage'"? The question seemed intended to answer itself — and not in a way favorable to Gomez or the conference.

But what did Gomez say that was so objectionable? In view of its setting, the full text of his speech would seem rather anodyne. The principal argument is that many Americans are suffering from a spiritual crisis to which God is the solution. Affirming that principle, especially before an audience of prelates, is pretty central to Gomez's job description.

That doesn't mean there's no political dimension to Gomez's statements. But it's rather less threatening than Jenkins' invocation of Christian nationalism suggests. The speech begins with a tribute to John Ireland, the turn-of-the-century archbishop of St. Paul, Minnesota, who served as chaplain to the Union army while a young priest and was associated with ecclesiastical and political progressivism in his maturity. In Gomez's telling, "Ireland believed deeply in what Reverend Martin Luther King and others have called the 'American creed' — the belief expressed in our founding documents, that all men and women are created equal and endowed with sacred dignity, a transcendent destiny, and rights that must never be denied."

There may be a sense in which this position can be described as an expression of Christian nationalism. But not much more so than the Gettysburg Address, which had its 158th anniversary on Friday. Lincoln was not conventionally pious, but as the Civil War progressed he increasingly tended to describe the conflict in religious terms derived from the Hebrew Bible. The essential caveat, which distinguished his tragic theodicy from more militant contemporaries, is that Americans were an "almost chosen people" rather than the unconditionally designated representatives of the Lord.

Until fairly recently, Gomez's way of describing the religious sources of "the American creed" was not very controversial, either. In addition to civil rights figures like King, political leaders of both parties routinely employed biblical rhetoric, appealed for God's blessing of the United States, and argued that Christians and Jews shared a special ethical connection. Rather than expressing a novel and sinister brand of populist nationalism, these habits belong to the postwar heyday of ecumenical religion and liberal patriotism. As President Dwight D. Eisenhower famously, if somewhat obscurely, put it, "our government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don't care what it is."

There are three main reasons this kind of talk now strikes many as retrograde and divisive. The first and least important is the increasing reality — and recognition — of religious pluralism. Gomez's remarks evoke a time when Protestant, Catholic, and Jew were the basic categories in American religion. Although a majority of Americans continue to identify as Christian of some kind, the menu of statistically significant options is now much expanded.

It should be possible to accommodate growing populations of Muslims, Hindus, and others in America's theologically capacious tradition of civil religion. We now tend to forget something Ireland's generation knew firsthand: that Catholics' capacity for participation in a republican political community was once widely doubted. In their original uses, terms like "Judeo-Christian heritage" and "biblical worldview" were not exclusive. On the contrary, they were intended to expand the boundaries of Americanism beyond old-stock Protestants. In that respect, Gomez's appeal to a religious basis for politics is perfectly compatible with his advocacy for immigrants.

A bigger change is the diminishing cultural authority of any traditional religion. The portion of the population that is personally devout may not have changed much over the last half century. But religious leaders and institutions used to enjoy significant influence over lukewarm adherents and even outright nonbelievers as well as over their more committed followers. For much of American history, Protestant churches were a kind of "soft establishment" that set conventional and in some cases legal boundaries for the conduct of American life. By mid-century, Catholics were doing perhaps more than their part, as groups like the National Legion of Decency set terms for the entertainment industry (a role brilliantly satirized in the Coen brothers' film Hail, Caesar!).

It's nostalgia for this informal influence that provokes some of Gomez's critics — including religious ones. Within Christian circles, Jake Meador argues at Mere Orthodoxy, the "Christian nationalism" discussion is less about whether greater piety is desirable in the future than whether it actually existed at an earlier time. Where conservatives see decline from an imperfect but morally coherent culture, progressives (or, in evangelical circles, the comparatively progressive) accuse them of turning a blind eye to the sins of the past. That very much includes the influence of racism within religious communities, which Gomez has been accused of ignoring.

The third and perhaps most important change is quite recent. Critics of Christian conservatism have been warning for decades of secret plans to seize power. Before the last months of the Trump administration, it was tempting to dismiss those fears as alarmist. But the efforts of a sitting president to prevent the inauguration of his opponent, including personal encouragement of the mob that stormed the Capitol, bring the nightmare of a coup d'etat too close to reality. The riot of Jan. 6 is the main reason the term "Christian nationalism" has entered the mainstream.

Despite some overlap in rhetoric, though, Gomez and the rioters diverge on the key issue: Where figures like author and radio host Eric Metaxas inspired believers to engage in militant politics, Gomez called for spiritual renewal. That's exactly the role secularists say they want religious leaders to take.

The danger in Christian nationalism isn't when it calls the faithful to profess their beliefs or the nation to judgment before God. It's when it claims the right of the ostensibly devout to execute that judgment with their own hands, contrary to the constitutional order.

If the political enforcement of Christian principles is a problem, then, a restoration of churches and religious communities outside government is the solution. Unless you think religious belief is simply going to disappear — a scenario that's possible in Western Europe but very unlikely in the more pious U.S., where even the so-called "nones" continue to report some degree of religious belief and practice — that spiritual and ethical enthusiasm will find an outlet. The question is only what outlet it will be.

Denouncing Gomez's old-fashioned creedal patriotism as Christian nationalism isn't just an unfair use of an often misapplied concept, then. It risks discrediting a powerful alternative to genuinely threatening movements. It risks pushing those to whom Christian nationalism appeals deeper into the nationalism and away from the Christianity.

You may also like

Stadium name absurdity peaks with L.A.'s Crypto.com Arena

A Harry Potter reunion is happening, reportedly without J.K. Rowling

Virginia local school board reverses ban of 'sexually explicit' books after public outcry