Christmas in Ortona: Remembering a legendary 1943 Canadian WW II battle

Eighty years ago, as some Canadian troops enjoyed a Christmas dinner that included roast pork, vegetables and beer at a church in Ortona, Italy, their fellow troops were busy fighting nearby in the rubble-filled town.

While Ortona is legendary for the Christmas dinner and the ingenious tactic the Canadians used to capture the town in the bloody eight-day battle, a forgotten detail is how a regiment from Nova Scotia helped pave the way to Ortona.

Lee Windsor, a history professor at the University of New Brunswick, said about three-quarters of the Atlantic Canadian units that served in the Second World War fought in Italy.

"Only a small number by comparison go to Normandy, so the national commemoration effort that focuses so much on Normandy in northwest Europe really leaves out Atlantic Canadians," he said. "So it's not only a forgotten campaign for the war as a whole, it's particularly troubling, I think, for Atlantic Canadian veterans stories."

The Italian Campaign that began in July 1943, was an effort by the Allies to loosen Adolf Hitler's grip on Europe. By fighting in southern Europe, the Allies believed it would spread German manpower and make it easier to take western Europe during the Allied invasion of Normandy, France, on D-Day: June 6, 1944.

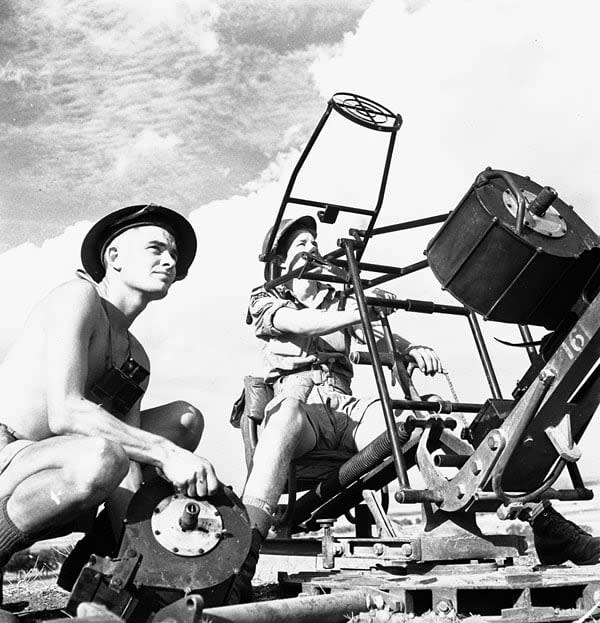

Privates Roger Widdifield, left, of the West Nova Scotia Regiment, and Everett Dewar, Saskatoon Light Infantry (M.G.), attached to the West Nova Scotia Regiment, man an anti-aircraft gun, in Spinazzola, Italy, on Oct. 1, 1943. (Alexander M. Stirton/Canada. Dept. of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/PA-189891)

After capturing the island of Sicily, Italy, in the summer of 1943, the Allies headed to the mainland with the aim of capturing Rome.

"They thought it would be fairly easy. We'll cross into the mainland and we'll just work our way up. It wasn't quite as easy as they hoped," said Julie Thomas, the chief curator at the Army Museum Halifax Citadel.

Gen. Bernard Montgomery, standing on a 'duck,' speaks to Canadian troops in Pachino, Italy, on July 11, 1943. The Italian Campaign started on July 10, 1943, in the Sicilian region and ran until Aug. 6. The fighting then moved to mainland Italy beginning Sept. 3. (National Archives of Canada/Frank Royal/PA-130249)

Part of the challenge was the Apennine Mountains, which run down the heart of Italy, meaning any advance by the Allies could only happen east or west of the mountains. As well, many rivers flow out of the mountains, which allowed the Germans to put up defensive line after defensive line and slow the advance of the Allies.

Thomas said that as the Allies worked their way up the boot of Italy — Italy's geography is often referred to that way because it resembles the shape of a boot — the Germans often pulled out quickly. As the Canadians approached Ortona, they didn't expect the Germans to mount much of a defence.

That all changed in early December at a land feature that came to be known as The Gully. On the map, it was a narrow line that ran from the Apennine Mountains to the Adriatic Sea, which is on the eastern side of Italy.

"Canadian intelligence completely failed to appreciate the significance of this position," said Mark Zuehlke, the author of several military history books, including ones about Ortona.

Sgt. George Game films between two German bodies on the outskirts of San Leonardo, Italy, near Ortona, on Dec. 10, 1943. (Photo by Lt. Frederick G. Whitcombe, Library and Archives Canada, PA 147111)

He said The Gully was about a half-kilometre wide and 300 metres at its deepest point.

Zuehlke said the Germans dug a foxhole into the south bank of The Gully and would hide inside while the Canadians shelled the area. But when the shelling stopped, the Germans would fire their machine guns as Canadians would run into a "wall of fire."

Members of the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada are forced to follow a narrow footpath for two miles along the hilly Adriatic coast during the Allied advance through Italy in the Second World War. The path leading into Ortona had to be cleared of mines before the Canadians could proceed. (Department of National Defence/The Canadian Press)

Among the troops fighting at The Gully was the West Nova Scotia Regiment, a unit created in 1936 that merged militias covering the Annapolis Valley and the South Shore.

War correspondent Greg Clark referred to them as "a rugged Maritime brotherhood of fishermen, miners, farmers, apple growers, not to mention drug clerks, storekeepers, truck drivers, schoolteachers, schoolboys."

'Determined people'

Thomas notes the West Nova Scotia Regiment fought valiantly.

"They don't give up any land," she said. "They don't retreat. They get in there and they keep fighting until everything is over. They're just determined people."

The breakthrough at The Gully came from the Royal 22nd Regiment, better known as the Van Doos, that managed to outflank the Germans from the west, which forced the Germans to retreat from The Gully.

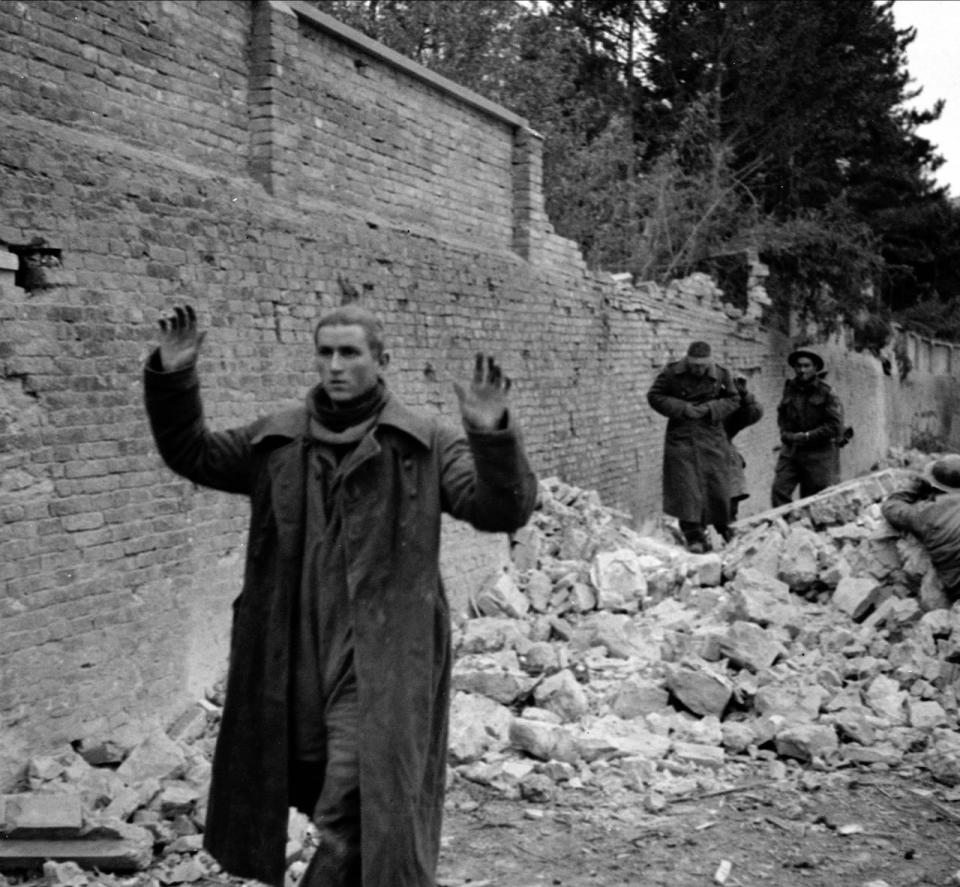

German soldiers surrender to personnel of the Loyal Edmonton Regiment in Ortona on Dec. 21, 1943. (National Archives of Canada/T.F.Rowe/PA-107934)

While the West Nova Scotia Regiment advanced toward Ortona, it didn't take part in capturing the town partially because of how many men they had lost. Thomas said the regiment lost 18 officers alone in the Battle of The Gully, including their commanding officer.

"But they also had been in combat for 16 days straight without respite of any kind as they pushed hard to break this line," she wrote in an email to CBC News. "Other groups such as the Seaforth Highlanders [of Canada] had been pulled back and given rest, so they were the ones to take up the challenge in Ortona."

Members of the Loyal Edmonton Regiment have tea and sandwiches outside battalion headquarters in Ortona on Dec. 21, 1943. (Lieut. Terry F. Rowe/Canada. Dept. of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/PA-130064)

Ortona was attractive to the Allies because it had a port they could send supplies to, which would be crucial to the aim of capturing Rome.

But this also posed a challenge in how the Canadians planned to capture Ortona.

"There's no air support … to help take out some German targets or anything like that," said Thomas. "They're trying to not damage the infrastructure of the port and the train station that's there."

How mouseholing won Ortona for the Canadians

The fighting at Ortona began Dec. 20.

Adding to the complexity is that the Germans essentially booby-trapped the town, blowing up buildings to create piles of rubble and funnelling the Canadians to advance through certain routes in the town.

The Canadians improvised, employing mouseholing, a tactic that called for setting off explosive charges from the inside of the adjoining walls of the buildings that were standing. They then fired their machine guns and cleared out the building of any Germans. This kept the Canadians from being picked off in the streets.

'Real cat-and-mouse game'

Zuehlke said the Germans started setting booby traps such that when the Canadians entered the buildings, explosives would be set off.

"It becomes this real cat-and-mouse game," he said.

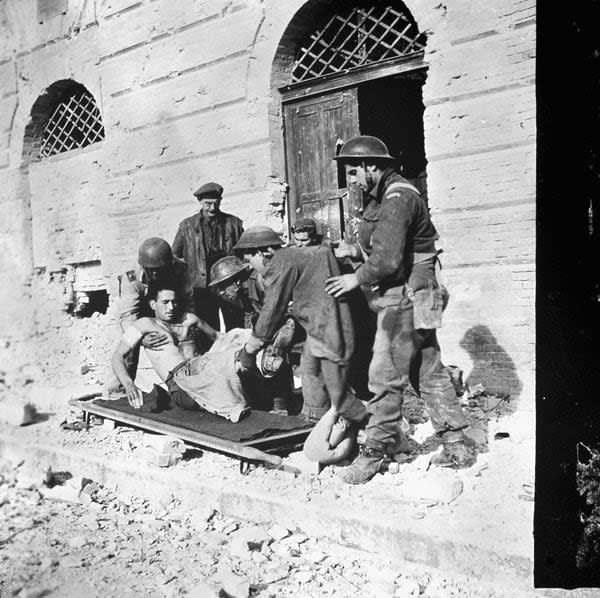

First-aid personnel of the Three Rivers Regiment place Sgt. Johnny Marchand on a stretcher in Ortona on Dec. 21, 1943. (Lieut. Terry F. Rowe/Canada. Dept. of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/PA-163927)

While the Canadians thought they had invented this warfare tactic, it was actually something the British taught, said Zuehlke.

"But Canadians didn't take that training, so they didn't know about that," he said. "And so they figured it out themselves."

Christmas in Ortona

Even the fighting wouldn't prevent the Canadians from enjoying a Christmas dinner.

"It's a bit of a legend in Canadian military history, the Christmas dinner in Ortona," said Zuehlke.

Troops from the Loyal Edmonton Regiment stayed on the front lines and a "primitive" Christmas dinner was delivered to them, which included a cold pork chop and a bottle of beer, said Zuehlke.

Meanwhile, the B.C.-based Seaforth Highlanders of Canada shuffled its troops in and out for a more proper dinner at a church that was a few blocks away from the fighting.

A Canadian soldier is rescued on Dec. 30, 1943, in Ortona. (Library and Archives Canada)

"On offer was soup, pork with applesauce, cauliflower with mixed vegetables, mashed potatoes and gravy," Zuehlke wrote in his book, Ortona Street Fight. "There was Christmas pudding and minced pie for dessert. And a couple of bottles of beer per man."

The Highlanders even sang some carols, before heading back to the front lines, swapping out for others who had yet to eat Christmas dinner.

The Canadians liberated Ortona three days later.

A Canadian soldier checks a German machine gun nest on Jan. 14, 1944, following the capture at Ortona. (Keystone/Getty Images)

According to Veterans Affairs Canada, there were more than 2,600 Canadian casualties in Italy in December 1943, with more than 500 deaths.

Almost 100,000 Canadians served in Italy during the Second World War.

MORE TOP STORIES