Christmas: From Scrooge to George Bailey and the Grinch, the inspiration behind our favourite festive stories

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

We cherish our favourite Christmas stories and revisit them every year, but rarely do we take a moment to consider their origins.

The likes of Ebeneezer Scrooge, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and the Grinch are fixtures of the festive season and the circumstances surrounding their conception are frequently fascinating.

Here’s how some of our most-loved Yuletide tales were spun.

A Visit from St Nicholas (1823)

More popularly known as “Twas the Night Before Christmas”, this poem by Clement Clarke Moore, a professor of Oriental and Greek Literature and Divinity in New York, did much to establish American Christmas traditions and the mythology of Santa Claus.

The verse – giving an astonished father’s eyewitness account of Santa’s arrival by flying sleigh – was first published in the state newspaper The Troy Sentinel after a friend of Moore’s submitted it without his knowledge.

Printed unattributed, there has been some debate about whether Moore really was the author. Henry Livingston Jr, a farmer and poet, also has a strong case for being its originator.

Whatever the truth, the result owes a debt to Washington Irving’s earlier book A History of New York (1809), which set down the seasonal traditions of the state’s Dutch settlers. Santa Claus, in fact, is an anglicising of the Dutch name for the character: “Sinterklass”.

A Christmas Carol (1843)

Charles Dickens' story of miserly moneylender Ebeneezer Scrooge, visited by ghosts on Christmas Eve urging his moral awakening, first went on sale on 19 December 1843.

The novelist was motivated to write it by a deeply felt outrage at the hardships of the urban poor he saw every day on the streets of Victorian London and the unfeeling avarice of the arch-capitalists of his age.

The author had known poverty himself as a child after his father, John, was incarcerated in the Marshalsea Prison in Southwark for debt, forcing the young Charles into hard labour at a boot-blacking workhouse.

In the winter of 1843, Dickens had visited Clerkenwell’s Field Lane Ragged School, a recently founded charitable institute for urchins. The deprivations of the pupils he encountered there only stirred his indignation.

Resolved to address his concerns in fiction, Dickens returneâd to an idea he had first touched upon in The Pickwick Papers (1836): the sinner shocked into a change of heart by supernatural intervention. In that novel, Mr Wardle tells the story of Gabriel Grub, a church sexton visited by goblins, who show him his past and future and inspire a more charitable attitude.

The tale of Scrooge’s conversion from penny-pinching humbug to zealous altruist provided a cheering moral, but also set in stone our popular conception of the Victorian Christmas, a time of candlelight and plum pudding, undoubtedly two central reasons for its enduring popularity.

Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1939)

According to the custom established by A Visit from St Nicholas, Santa’s sleigh is pulled by eight reindeer. Not so, this charming story by Robert L May informed readers.

Rudolph is the ninth, overcoming mockery at his unusual glowing red nose to play a vital role in guiding the carriage through the murky night skies.

May worked as an advertising copywriter for the Chicago department store chain Montgomery Ward during the Great Depression, and was assigned to develop a character that would help sell colouring books in December.

He was inspired by his four-year-old daughter Barbara’s love of deer at the city zoo and conceived the idea for the nose by watching mist rise from Lake Michigan from his office window, realising the sleigh would need a lamp to light its way.

Tragically, the author’s wife Evelyn died of cancer during the writing of Rudolph but he pressed on, taking solace in his confidence that the story would bring pleasure to children.

Rudolph’s commercial origins were quickly forgotten and he was soon absorbed into Christmas lore, the subject of a favourite nursery rhyme.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)

Frank Capra’s seasonal drama sprung from an unusual source: a Christmas card itself.

Philip Van Doren Stern, a historian of the American Civil War, had written a 21-page, 4,000-word short story, “The Greatest Gift”, to amuse himself in November 1939 and sent it on to a number of magazines for publication, all of whom rejected it. Coming across it again four years later, he decided to include a copy in the greetings cards he was sending out to friends.

One found its way into the hands of Cary Grant’s agent, Frank Vincent, who proposed it as a vehicle for his client. RKO snapped up the rights for $10,000 but failed to develop it into a workable screenplay, passing it on to Capra’s new production company, Liberty Films.

Nine script doctors – Capra, Dalton Trumbo, Dorothy Parker and Clifford Odets among them – would work on it before the draft was deemed satisfactory.

James Stewart, rather than Grant, ended up playing the part of George Bailey, a bank lender who wishes he’d never been born, until angel Clarence Oddbody (Henry Travers) shows him a nightmare world without him.

Stewart had returned from the Second World War, where he had distinguished himself as a bomber pilot in the US Air Force, and resolved to give up acting to dedicate himself to more “worthwhile” causes.

Capra, though, persuaded him that storytelling provided an invaluable public service and the conviction Stewart brought to the part of Bailey proved to be amongst his very best work.

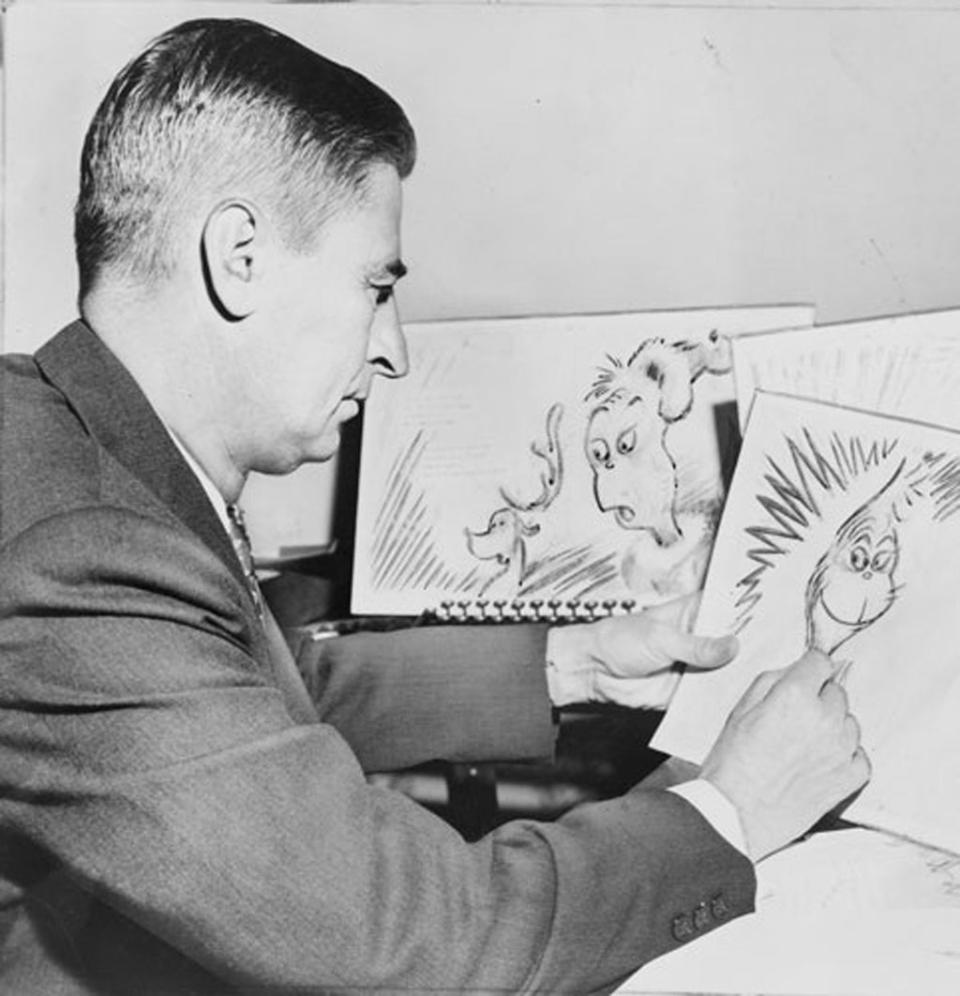

How the Grinch Stole Christmas (1957)

Dr Seuss had first conceived of the Grinch two years before he was given a solo story.

The character had appeared in a 32-line fable, “The Hoobub and the Grinch”, which was printed in Redbook magazine and is now collected in Horton and the Kwuggerbug and More Lost Stories (2014).

In it, the Grinch takes advantage of a good-natured creature by selling him a piece of string, having persuaded the Hoobub the yarn is worth more than the sun.

Following the completion of The Cat in the Hat, Seuss (AKA Theodor Geisel), revisited the villain as a Christmas-loathing cynic, embodying some of the worst aspects he saw in his own character.

The author was 53 when he wrote the book and the Grinch complains of having put up with the joyous Whos for precisely the same number of years.

Seuss would later drive a car with the personalised plate “GRINCH”.

The Grinch's critique of the commercialisation of the season is among the most pointed in his output - even if the Whos do prove him wrong at the close.

‘Fairytale of New York’ (1987)

This undying classic from The Pogues and Kirsty MacColl is probably Britain’s favourite Christmas song and has deservedly kept songwriters Shane MacGowan and Jem Finer in pints of stout since 1987. The unnamed characters given voice by MacGowan and MacColl are an integral part of modern tradition.

Touchingly frank about lives as they are actually lived – spinning from disappointment to resignation to acceptance to consolation – the duet recounts the love-hate relationship between a pair of washed-up Irish-American immigrants, helplessly bound together, no matter how much they might resist it.

Actually recorded at the height of summer at RAK Studios in Regent’s Park, London, the barstool romance was written after producer Elvis Costello challenged MacGowan to compose a festive duet to be sung with bassist Caitlin O’Riordan, his wife and the latter’s bandmate.

“I sat down, opened the sherry, got the peanuts out and pretended it was Christmas,” MacGowan recalled in an interview with Melody Maker.

MacColl, married to producer Steve Lillywhite, was brought in to sing on the demo. She did such a good job that her voice was kept in the finished work, whose title is lifted from a 1973 novel by JP Donleavy.

Krampus (2015)

A comparatively recent addition to the Christmas canon, this inspired film from director Michael Dougherty follows in the tradition stretching from the Victorian ghost story to Gremlins (1984) in introducing horror to the hearth.

When a boy is driven to lose his Christmas spirit by the teasing of his dysfunctional family, he tears up his letter to Santa and a heavy blizzard descends. The weather heralds the arrival of Krampus, a horned goat demon in the service of Saint Nick, sent to punish the naughty by dragging them to Hell.

Just as Washington Irving had invoked Dutch festive folklore in his writing, Krampus takes its inspiration from the superstitions of Old Europe.

Krampus is part of the seasonal mythology of Austria, Bavaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Slovenia. Revellers dress as the figure in the Alps on 6 December to this day, but his origins are mysterious.

Some folklorists date the spirit back to pre-Christian ritual but the chains he is often seen to wear have been interpreted by many as an allusion to the Christian concept of “binding the devil”.

The controversial Dutch character Black Pete is a loose equivalent, although a far more benign presence.

The film conjures Krampus as a timely response to the rampant materialism of Christmas, opening with a brilliant satirical montage of deranged Black Friday shoppers competing for bargains.

Modern American interest in Krampusnacht has been credited to YouTube, and an increased global awareness born out of internet culture, with the monster now regarded as an antidote to the sentiment of the season for contrarians. He has also appeared in a snuff film episode of the BBC's ghoulish comedy Inside No. 9 with Reece Shearsmith and Steve Pemberton.

Only Donald Trump in Home Alone 2 (1992) casts a more sinister shadow.