Christo helped revive Miami by dressing Biscayne Bay islands in pink. He died Sunday

They cloaked Berlin’s Reichstag in fabric, shaded Japan and Southern California with thousands of umbrellas and installed more than 7,500 orange vinyl gates in New York’s Central Park, creating ambitious but temporary environmental art installations that became public sensations during their brief lives.

But Miamians will forever cherish iconoclastic artists Jeanne-Claude and Christo for wrapping 11 Biscayne Bay islands in floating pink fabric skirts for two weeks in 1983, a time when Miami was torn by racial and economic strife. The project fixed the world’s attention on a city that had been left behind, instilling unity and pride of place in its long-suffering residents, and in one swoop setting the stage for its revival.

Christo died Sunday at home in New York at age 84, just two years after an expansive exhibit at the Perez Art Museum Miami commemorated the 35th anniversary of “Surrounded Islands,” the project he created with his late wife and artistic partner, Jeanne-Claude.

For PAMM Director Franklin Sirmans, the timing of Christo’s death is unmistakably poignant.

“I can’t help but think that the spirit of Christo and Jeanne-Claude is wrapped up in all the things we’re dealing with today,” Sirmans said. “Everything they did was about bringing people together. They used art as a vehicle and a tool to help people see each other. ... He didn’t believe the work would change the world, but he did the work to bring people together to understand each other a bit better.”

Christo’s death was announced on the artist’s Twitter account and on his web page. No cause was given.

The statement said Christo’s next project, “L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped,” is slated to appear in September in Paris as planned. An exhibition about Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work is also scheduled to run from July through October at the Centre Georges Pompidou.

“Christo lived his life to the fullest, not only dreaming up what seemed impossible but realizing it,” his office said in a statement. “Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s artwork brought people together in shared experiences across the globe, and their work lives on in our hearts and memories.”

Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon died in 2009 at age 74 from complications of a brain aneurysm. Although their jointly produced works were first credited only to Christo, her name was added as full co-creator in 1994. They met in Paris in 1958. They were born on the same day (June 13) in the same year (1935), and, according to him, “In the same moment” and would become partners in life and art.

Christo Javacheff, who as an artist used his first name only, was a refugee from Communist Eastern Europe who left his native Bulgaria in search of artistic freedom, eventually settling with Jeanne-Claude in New York.

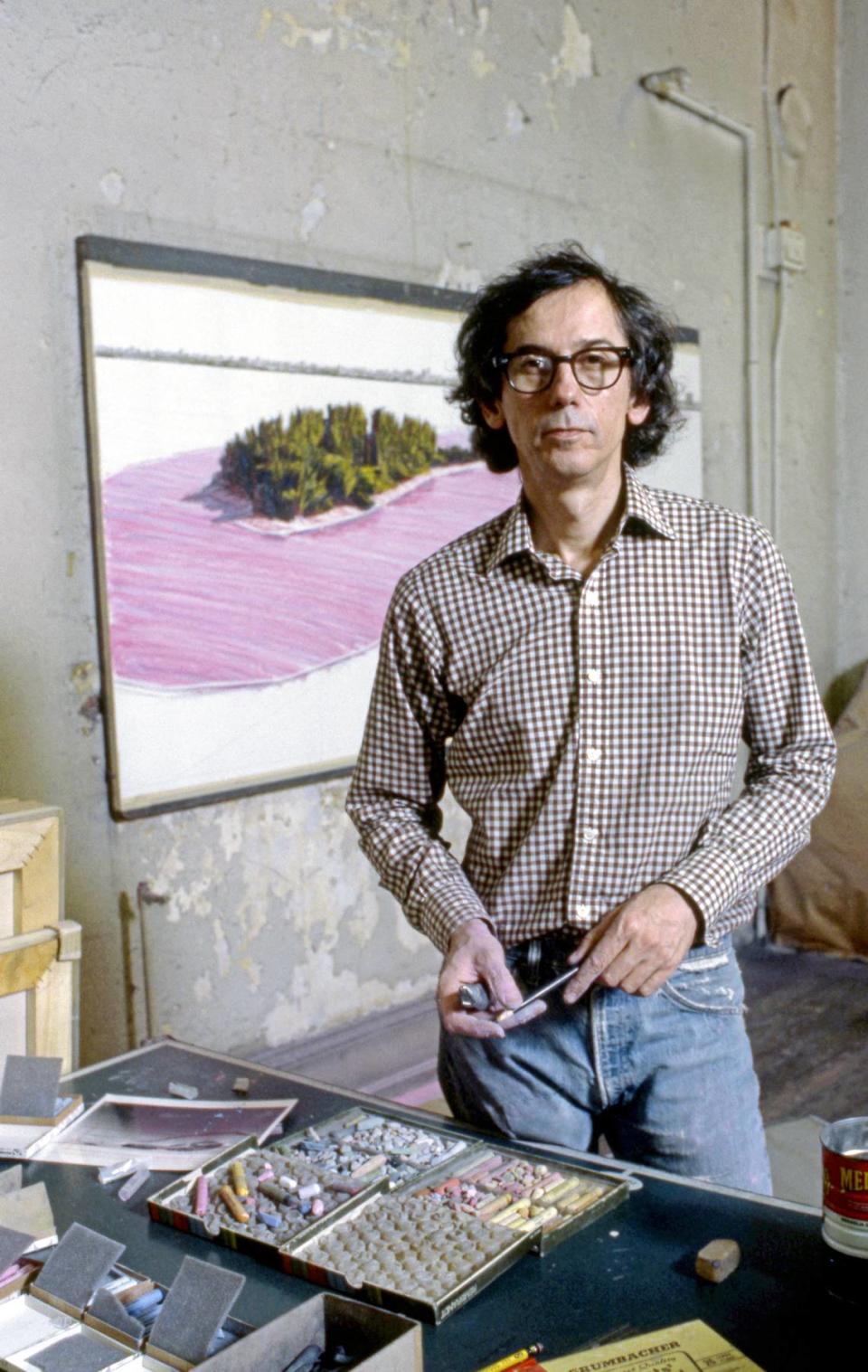

The two made a point of paying for all of their works on their own and did not accept scholarship or donations. Instead, they sold preparatory drawings, collages, scale models and original lithographs to earn enough to finance their dreams.

“I like to be absolutely free, to be totally irrational with no justification for what I like to do,” he said. “I will not give up one centimeter of my freedom for anything.”

Christo and Jeanne-Claude were already well known for audacious, ephemeral works of environmental art that often entailed wrapping monuments in fabric when they were invited to consider working in Miami by Jan van der Marck, founding director of what would become PAMM. They were struck by the beauty of Biscayne Bay and the trash-strewn spoil islands in its midst. It was Jeanne-Claude’s idea to wrap the islands in pink, Christo recalled in a 2018 interview with the Miami Herald.

“We were very inspired by the horizontality of the site. You had this incredible area of Biscayne Bay,” Christo said. “I remember we were looking at the islands. They were lonely, like they dropped from the sky in the water.”

What would follow was three years of an intense political and legal fray, every bit of it recorded and documented as an integral part of the art project, before the couple barely won approval to move forward from a divided Dade County Commission. Environmentalists lambasted the idea and sued to stop it in federal court, where they lost. Finally, Christo, Jeanne-Claude and a 430-person crew laboriously unfurled millions of square feet of specially made pink fabric for seven miles up and down the bay amid public skepticism and blustering late-spring squalls.

It was a jubilant success, sparking a long-lost hometown pride as images of those pink-skirted islands, which seemed to float like giant artificial lily pads in a vast urban pond, were broadcast and published around the globe, Thousands of Miamians lined causeways and condo balconies and chartered planes and helicopters to fly over the bay. Then, after two weeks, it was all taken down, leaving no trace.

To Christo, all of it was an integral part of the artwork.

For Miami, the impact was immeasurable, said PAMM curator Rene Morales, who as a child was taken to see “Surrounded Islands” by his Cuban exile father.

“ ‘Surrounded Islands’ was the catalyst for Miami’s evolution to a center for contemporary art,” Morales said. “It played the important role of serving as an example of the great benefit that contemporary art can have for a city, and in that sense it set the city up to be ready for Art Basel and the growth of its art community and art institutions.”

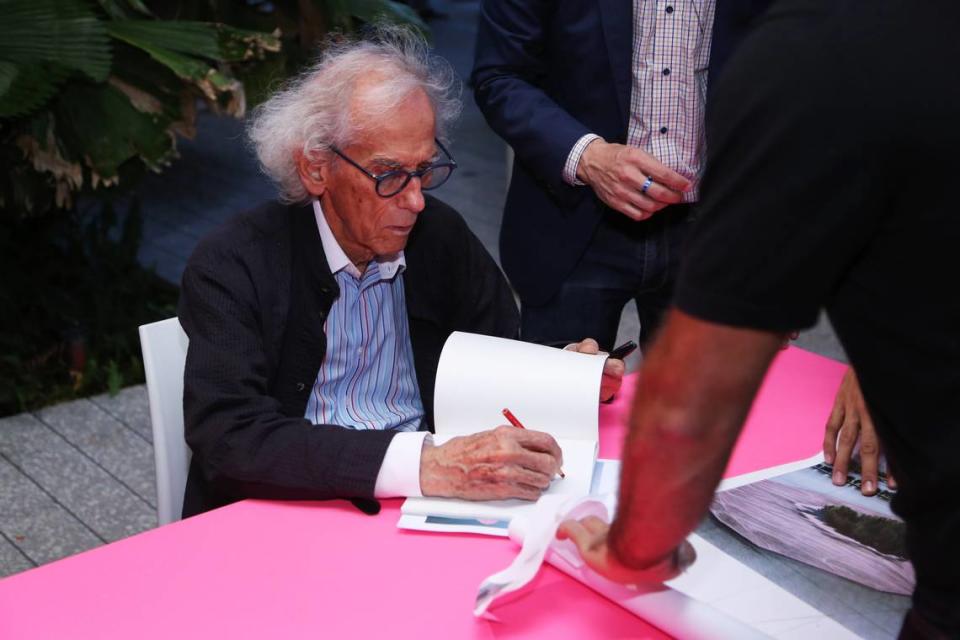

Morales organized the 2018 exhibit that detailed its elaborate development through leftover materials and extensive documentation. Morales said Christo lived up to his reputation as warm, approachable and organized to the hilt.

“The process of creating that exhibition was incredibly positive. He was so personable, and his team worked in an intimate, close family-like way, it went so smoothly,” Morales recalled on Sunday. “His energy and his passion are just so strong and infectious; they changed you a bit.”

Christo was already wrapping smaller found objects, like cars and furniture, when he met Jeanne-Claude. The projects’ scale broadened after they joined forces. Within three years they were working together on an installation of oil drums and tarp on the docks in Cologne.

The year 1968 would prove pivotal for the couple with three endeavors: “Wrapped Fountain”;” Wrapped Medieval Tower”; and “Wrapped Kunsthalle.” The next year brought “Wrapped Coast,” which involved 1 million square feet of fabric and 35 miles of rope across a 1.5-mile-long section of the Australian coastline, and the wrapping of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.

Their works were grand in every respect, from manpower to impact. More than 600 workers were involved in putting up Central Park’s “The Gates,” and 300 more in dismantling them. More than five million people saw the installation, and it was credited with injecting about $254 million into the local economy.

This report was supplemented with material from The Associated Press.