Christopher Plummer, a reading actor, found divinity in Shakespeare's words

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

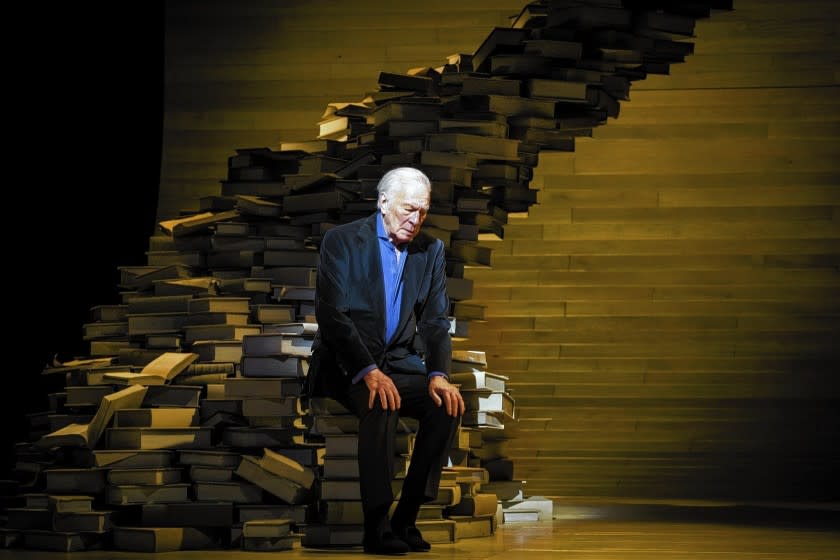

When Christopher Plummer appeared at the Ahmanson Theatre in “A Word or Two,” his costar was a mountain of books. He was delighted to be in such excellent company.

The 2014 solo show had the feeling of a four-star general touring old battlegrounds before retiring to civilian life. But Plummer wasn’t going anywhere.

He had won an Oscar only two years earlier, his first, at age 82, for his slyly touching performance as a dad who comes out of the closet as a senior citizen in Mike Mills' film "Beginners." Still to come was another nomination for his portrayal of J. Paul Getty in “All the Money in the World.” Actors may pull back from the grind of the stage but they never stop working, if there’s a role they can make their own.

Plummer, who died last week at 91, wasn’t bidding his fans farewell when he made his return to the Ahmanson, where he had reprised his Tony-winning turn in “Barrymore” in 1998. He was saying thank you to the writers who had shaped and guided his talent.

“A Word or Two” was a paean to great literature and the power of the written word. Plummer, a Canadian exemplar of the classical stage, was a Shakespearean through and through. If he could be snarky about the fame that followed him from playing Captain Von Trapp in “The Sound of Music,” it was chiefly because those mountains he had climbed in the tragic repertoire — Hamlet, Macbeth, Iago, Lear — meant more to him than his celebrated march through the Austrian Alps of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical.

It was through dramatic poetry that Plummer discovered his voice, which he developed into one of the supplest instruments of the modern stage. Playwrights guided him down this path but poetry, novels and enduring writing more generally nourished his quest.

Like Richard Burton, he was an intrepid stage animal in public and a bookworm in private. He was also bibulous like Burton and fondly recalled nights out carousing with Burton and other hard-drinking classical actors of the period, such as Jason Robards and Peter O’Toole, until health, sanity and marital injunction forced Plummer to clean up his act.

Wafting in the Shakespearean sublime one minute, sozzled in a dark pub with theater cronies the next, Plummer received an immersive education in both the majesty and the frailty of the actor's life. To do justice to the grand tragic roles requires a knowledge of extremes, but longevity in the theater demands discipline.

Plummer didn't let his destructive habits shortchange his career. But in "Barrymore," he played another actor, John Barrymore, who waited too long to rein himself in. Summoning back to the stage the bleary-eyed thespian who destroyed his gift en route to becoming one of the first Hollywood superstars, Plummer paid homage and bore witness to a figure he understood only too well.

Drink was Barrymore’s undoing, and in the fictional setup of William Luce’s play, the actor is attempting to rescue his career with a stage comeback. Plummer captures both the pathetic hamminess of the old trouper who can’t remember any of his lines and the glory of the artist who is occasionally able to take flight on Shakespearean words before crashing back down to an empty theater.

When an actor of Plummer’s stature dies, it marks not simply the loss of a singular talent but the severing of a connection to an august tradition. The status of the classical actor, once regarded as the pinnacle of the field, has diminished as screens have expanded their monopoly on drama.

Great acting is judged today through close-ups that younger audiences are more inclined to view as clips on their pocket devices. The Method, in all its many manifestations, has won the cultural battle. Actors, training for the camera, are worried more about inner truth than polished technique. The road to psychological realism is presumed to cut through personal history.

Stella Adler, one of the great acting teachers of the 20th century, knew this was not just misguided but a misreading of Stanislavski, the source of the Method's approach. Imagination is what must be mined, not childhood trauma. One should rise to meet the great dramatic characters, not bring them down to our petty level. Experience for an actor is invaluable, but it mustn't function as a restraint. There are more things in heaven and Earth than are dreamt of in our limited biographies.

Plummer arrived at this understanding the old-fashioned way, through working in the theater. By the time he made his debut at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in 1956, he had already amassed an extensive résumé of stage credits. He hungered for more, realizing that in cycling through the Shakespearean gamut he was refining skills, expanding his range and, most important, amplifying his soul.

His devotion to literature in all forms was part of his commitment to his craft. At the end of “A Word or Two,” he preached from the gospel that had redeemed him: “We must implore, beseech, entice, cajole, persuade, induce the children to read everything of value, of beauty, while they’re young or what’s a heaven for?”

The reading actor isn’t a thing of the past, but the value of a refined literary sensibility is less celebrated today than social media savvy. Plummer’s death compels us to reflect on the way the highest reaches of poetry and prose can endow an actor with a touch of immortality.

Hal Holbrook, who died in January, is another example of a performer who hitched his wagon to a literary genius and discovered that he could fly to the stars. For Holbrook, it was the wit and wisdom of Mark Twain that opened boundless vistas. Donning a white suit and wielding a cigar, he learned from the master he was embodying. Night after night, in front of audiences of varying disposition, he sharpened his timing and honed his instincts not just for his traveling show but for all his subsequent work on stage and screen.

Shakespeare was Plummer’s tutor, and by the time I saw him in Jonathan Miller’s production of “King Lear” at Lincoln Center, he was a master of his craft. On balance, he was probably the finest Lear of my theatergoing career. Paul Scofield gets the nod on film and Laurence Olivier on TV, but in terms of my stage Lears it comes down to two, Ian Holm and Plummer.

Plummer’s Lear may not have been as naturally irascible as Holm’s, but he brought Lear’s seniority to dribbling life. His Lear was a "foolish fond old man," shot through with belated regrets. Capricious, volatile, egomaniacal and, yes, stagy, he was in the end culpably human. When he howled, the heavens cracked. And when he asked Cordelia for her blessing, we wept.

Artifice and naturalism were virtuosically fused in his performance. Magnificent literature — the true secret of his trade — showed Plummer the way.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.