Chrysler Wanted a Lamborghini-Badged K-Car

In 1986, I left Ford for Chrysler, joining a group that then Ford CEO Don Petersen called “the band of misfits.” It was a promising time. Chrysler soon absorbed American Motors, and in 1987, Lee Iacocca announced another triumph: the acquisition of Lamborghini for $25 million. “And I didn’t buy it because I want a company that produces 300 cars a year,” he told the executive team. “There’s tremendous value in the brand. I want you guys to figure out what to do with it.”

From the August 2019 issue of Road & Track.

I pretty much knew what the master merchandiser had in mind: Lamborghini would become an uplevel Chrysler trim, the same way that the storied name of Italian coachbuilder Carrozzeria Ghia came to denote the most luxurious Ford Granadas and Mustang IIs. All it would require was more expensive leather, rampaging-bull badges, and the familiar Lamborghini script displayed prominently inside and out. In other words, the boss didn’t much want to preserve Lamborghini or its heritage. He wanted to milk the Italian luxury brand’s image for additional profit on Chryslers.

We could all see the irrefutable logic in the scheme. But the few real car guys and gals in the company were, well, appalled. Tom Gale, the vice president of design, asked me what he should do. My advice was to enact what I call “malicious obedience.” Give the chairman that “Lamborghini Edition” he craved, but make it so over-the-top that even he could see the folly of his request.

Tom set about his grim task: He started with the longest-wheelbase K-car variant available, the over-ornamented Chrysler Imperial. He stripped off the vinyl roof, lowered the chassis, painted the car a bright Italian red (including the hideous “Greek temple” grille), and shod the Chrysler with Lamborghini wheels and tires. The interior lost its life-inside-a-trombone-case purple velour in favor of buttery-soft light-tan leather. Lamborghini badges were everywhere, even embroidered on the headrests. The front fenders and decklid loudly proclaimed this vehicle to be the Chrysler Imperial Lamborghini Edition. It was sacrilege, but I had to admit it was the best-looking K-car I had ever seen. Thankfully, the idea never made it to production.

François Castaing, the brilliant chief engineer who had come to us with the American Motors purchase, had better ideas for Lamborghini. Prior to AMC, Castaing had long been technical director for Renault Sport. He oversaw the French company’s hugely innovative Formula 1 operation and was the chief designer of the Renault RS10, the twin-turbo V-6 car that ushered in Formula 1’s turbo era.

François saw opportunity in the handful of highly creative engineers now available to him through Lamborghini. And unlike Iacocca, who viewed the company as an expendable marketing resource, Castaing had a vision: to create a respected, profitable competitor to Ferrari. This massive task, he reasoned, would require a successful Formula 1 racing program to provide the brand with the type of enthusiast credentials that Ferrari had earned through years of competition.

But forming a Lamborghini F1 team, complete with cars, drivers, transporters, and the hundreds of people required for a serious racing program was clearly out of the question. Such an effort would cost $200 million or more, eight times what Chrysler had paid for the brand. Though François could divert modest sums from his tightly controlled engineering budget, a full-blown F1 program was beyond his reach. But, he reasoned, why not have Lamborghini become an engine supplier to some of the private F1 teams? Surely Lamborghini had the talent, and with technical assistance from Chrysler in areas such as advanced materials and electronics, a competitive engine could be developed. I acquiesced and sold the idea to Iacocca as being beneficial to the luster of the brand.

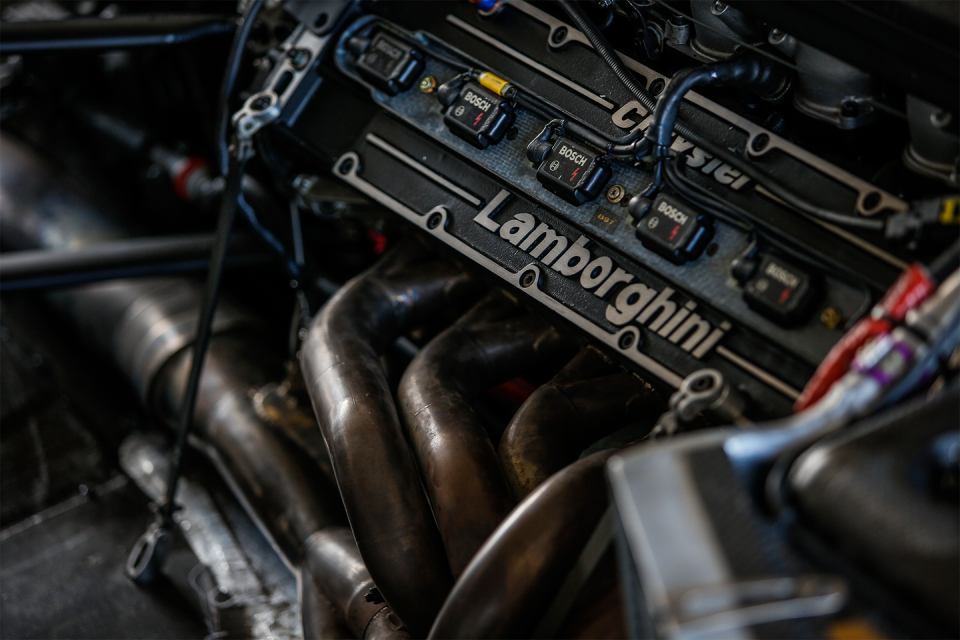

Meanwhile, at Chrysler headquarters, we were struggling with another long-shot project: the Dodge Viper. Originally, the concept had called for use of the cast-iron V-10 engine earmarked for the heavy-duty Ram pickup. But a great truck engine isn’t necessarily suitable for a sports car. It was heavy and designed for a maximum of 300 hp; the engine had small valves and a host of other basic flaws. François came to me with an idea: let the Lamborghini team convert our 8.0-liter truck lump into a lightweight aluminum engine, a task that would otherwise consume untold millions of dollars and many years if left to the mainstream Chrysler system. Lamborghini could do it in short order for around $10 million. I was initially reluctant to invest more into the Viper, which was the ultimate low-budget program. But, eventually, I saw the obvious value. This low-mass engine would improve vehicle balance and would be America’s first engine to reach 400 hp. (Pre-OPEC muscle cars and Carroll Shelby’s 427 Cobras advertised 400 hp or more but were well short of that by modern SAE measurement.) Thus, engine work at Lamborghini was greatly expanded and relatively well financed.

The Formula 1 engine, however, proved to be a disappointment. When the FIA banned turbocharging, it seemed like a perfect opportunity for a naturally aspirated V-12 engine. But the intended power levels were never fully achieved, and reliability was problematic. The motivated team at Sant’Agata received as much technical and financial support as François was able to provide. But it wasn’t enough. Over six seasons, Lamborghini supplied engines to five F1 teams, none of which scored a single victory or pole position. The best that a Lamborghini-powered F1 car managed was third place at the 1990 Japanese Grand Prix.

Meanwhile, the Chrysler mother ship was experiencing yet another major financial crisis. The vultures were circling, and we needed capital for the next generation of cars in the planning stages and for the revolutionary 1994 Ram pickups. Reluctantly, Iacocca agreed to shed pieces of the massive conglomerate he’d sought to build. Chrysler’s ill-fated investment in its rental-car business was sold. So was Gulfstream, maker of renowned executive jets, which Chrysler acquired in 1985.

Lamborghini had to go, too. Chrysler sold the brand in 1994, and dreams of ultra-prestige Imperials were abandoned. We did get that alloy V-10—beautifully reengineered, essentially an all-new design loosely based on the cast-iron original. The new heads featured the largest intake valves ever seen on an American engine. The aluminum engine delivered, making up to 460 hp and 500 lb-ft of torque in the first- and second-generation Viper.

Did the V-10 compete with the F1 program and harm Lamborghini’s efforts at establishing itself at the pinnacle of motorsport? We’ll never know, but I doubt it. The Formula 1 engine program might have been successful over time, but it was starved of resources. Meanwhile, first-gen Vipers had a genuine Lamborghini-designed engine under the hood, and their owners didn’t even know it. That may have been the greatest opportunity for Chrysler to use Lamborghini as a credible image enhancer, and we missed it.

You Might Also Like