The CIA, Hypnosis, and Cocaine: Why a Pilot Faked His Own Death in Front of His Family in 1977

On Sept. 18, 1977, Hazen, Arkansas’s Gary Betzner took a daytime drive with his wife and daughter in his El Camino to a dairy bar. Afterwards, he stopped on a bridge due to car trouble, opened the hood to check on the problem, and then suddenly and inexplicably dove into the White River. This sent his wife Sally into hysterics, and cast an immediate and terrible pall over his family, which—like everyone else in their small, rural southern town—was plagued by a single, persistent question: why?

[Spoilers follow]

For an answer to that query, directors Phil Lott and Ari Mark (and executive producer Adam McKay) turn to the one person who can best shed light on this seemingly tragic event: Gary himself, who winds up being not only the subject of their three-part HBO docuseries The Invisible Pilot (April 4), but its primary narrator. Sitting for extended chats in the present as well as at regular intervals over the past decade (via older footage shot by Craig Hodges, a friend of Gary’s son Travis), Gary proves a resurrected ghost at the outset of this latest true-crime affair. The fact that he didn’t commit suicide back in 1977, however, is only the first of many bombshells delivered by Lott and Mark’s venture, which begins with a bang before petering out once it trades entertainingly wacko criminality for sober political intrigue.

The Mysterious ‘Crypto King’ Who Stole $215M in Bitcoin and Wound Up Dead

Gary rose to local renown as an ace crop duster with unparalleled piloting skills; he was a daredevil who couldn’t resist performing flips, flying under bridges, and skimming his craft’s tires along the water. Sally met Gary on July 20, 1969, the night of the moon landing, and she describes it as a universe-shaking moment—a notion visualized by Lott and Mark through amusingly edited clips of the astronauts’ outer-space feat. Gary already had a wife, but once his daughter Polly was born, he got a divorce and married Sally, with whom he had two more children, Travis and Sara Lee. He established—and then sold—the Betzner Flying Service, moving his clan to Alaska for a pipeline opportunity that didn’t pan out. With few prospects and even less cash, Gary turned to another source of income: using his planes to smuggle marijuana.

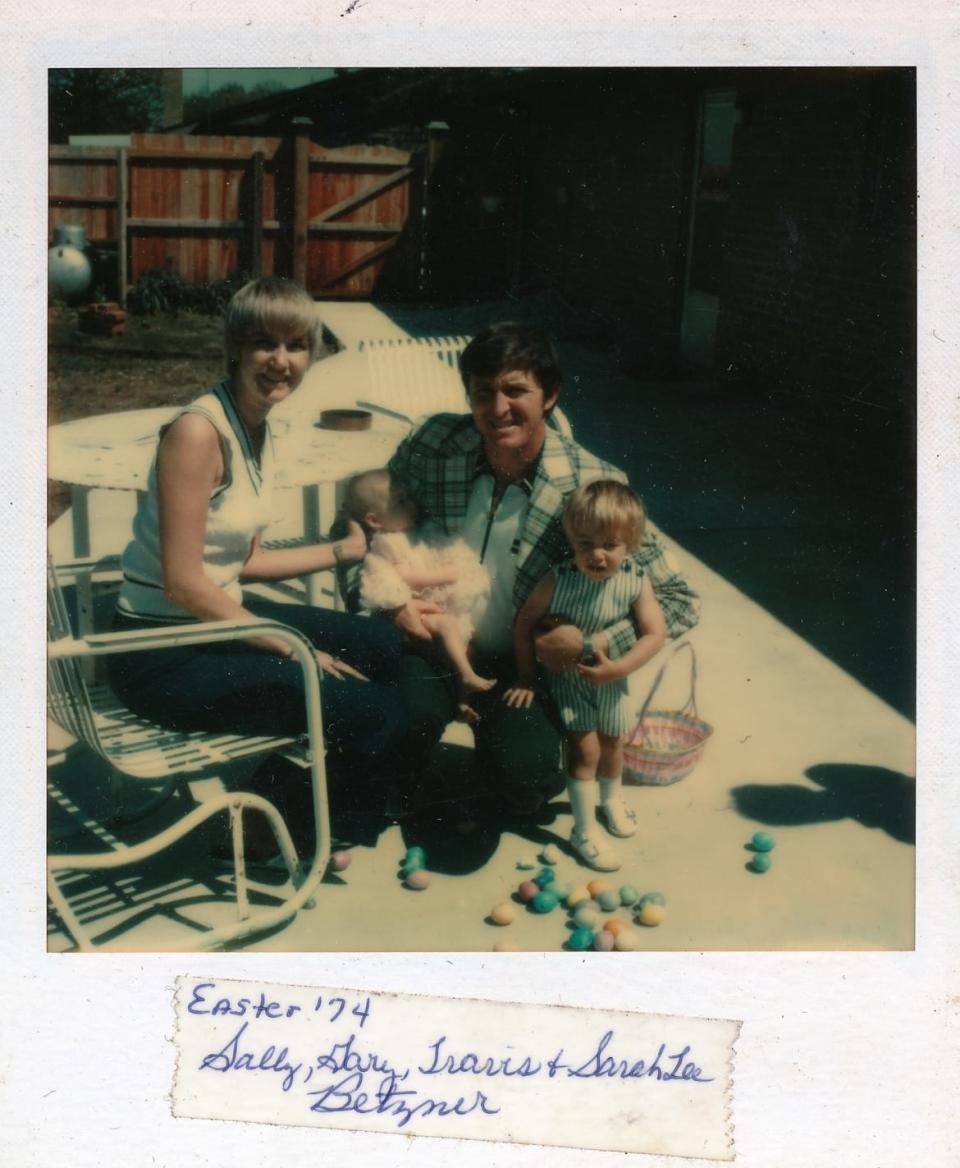

Gary Betzner with his family in 1974

A subsequent bout of painful gout led Gary to an unlikely cure: cocaine, a narcotic that he admits was used both to alleviate his ailment and for recreational purposes. When he was busted in a giant 1977 Miami DEA sting, though, Gary faced 20 years behind bars. Rather than do that stint, he decided to stage his death and go on the run. To guarantee that this ruse went according to plan, he and Sally took a three-month self-hypnosis course in order to program Sally into believing the lie that Gary was really dead. Somehow, this insanity worked and Gary successfully went on the lam, during which time he became a drug-advocating hippie named Lucas Noel Harmony who saw nothing wrong with either consuming or transporting illegal substances. Before long, he was revealing his still-breathing existence to a stunned Travis and Sara Lee in Hawaii (where they all lived as nudists), and he eventually found himself employed as a smuggler for George Morales, a Miami speedboat racer with deep ties to Pablo Escobar’s Medellín Cartel in Colombia.

If Morales sounds familiar to true-crime aficionados, that’s because he was prominently featured in Billy Corben’s Cocaine Cowboys: The Kings of Miami, a similar tale of bold criminals living the high life while evading the law. Yet what begins as a crazy saga about an outlaw flipping the bird to authorities – both figuratively and, on more than one occasion, literally – soon takes a drastic turn once Gary starts flying cocaine for his Colombian bosses, and then military cargo for individuals directly linked to the CIA. It’s at that point that The Invisible Pilot becomes not merely a stand-alone story about defiant wrongdoing, but a piece of the Iran-Contra puzzle, since Gary was now transporting guns to the Contras, and returning to U.S. shores with kilos of cocaine sought by U.S. government officials.

A lengthy prison sentence and cooperation with John Kerry’s subcommittee investigation into Ronald Reagan’s Iran-Contra scandal ensued, although The Invisible Pilot can’t make any of this later action hum with electricity; despite first-person accounts from Gary, interviews with various other pertinent individuals, and considerable archival footage, the docuseries loses its momentum the more it shifts its gaze from Gary’s outrageous conduct to the president’s headline-making mess. Gary gets almost wholly lost in the shuffle for a stretch of the third and final episode, and that does much to sabotage the energy of the entire production. Similarly unfulfilling are those passages concerning Travis, Sara Lee and Polly, whose mixed-up emotions about their dad—a combination of anger, resentment, and love—never come into sharp focus, no matter their candid commentary about the ups and downs of living with a fugitive father.

The biggest drawback to The Invisible Pilot, however, is that it never knows how to view Gary. Lott and Mark are neither interested in reveling in his exploits nor in casting a critical eye at his selfish behavior and rebellious ethos; instead, the proceedings exude a tepid empathy toward him. Unfortunately, Gary himself does much to frustrate any compassionate consideration of his plight, what with him touting drugs as a means of magical liberation, smuggling as “a holy thing” and “a service to mankind,” and the murderous Escobar as “a legend, and rightly so. I would hope that his praises, not only as a smuggler but as a human being, would be sung.” Far from simply a go-with-the-flow counterculture rabble-rouser who thought everyone should be allowed to smoke some weed, Gary proves a narcissist full of hollow and amoral self-justifications.

Thus, by the time Gary gets around to railing against his unjust treatment at the hands of the CIA—who used him for their operation and then left him to rot in jail—any minor wellspring of sympathy has long since run dry. Whereas a shrewder docuseries might have had a more acute point of view about Gary, what emerges here is a mixture of astonishment and admiration that comes across as largely unjustified.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.