Cincinnati Children's study finds children picked up the pandemic pounds, too

Children got heavier through the coronavirus pandemic, worsening a generational weight problem and raising their risk for COVID-19, says a patient study at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center released Tuesday.

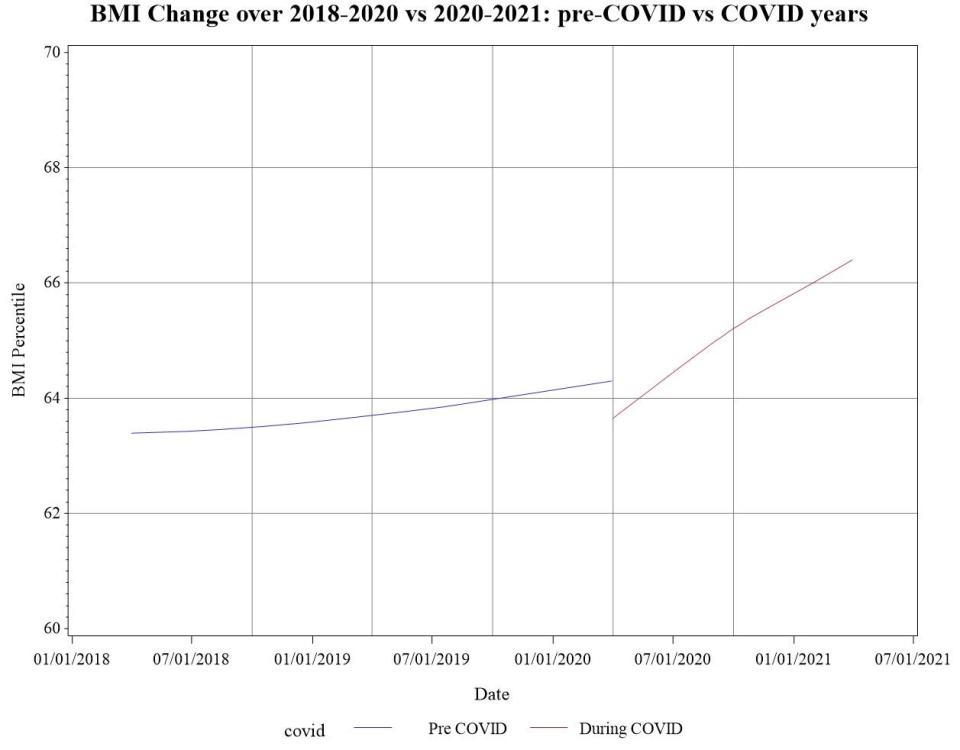

The 10-year tracking study found the percentage of children at unhealthy weights rose from 35% to 36.4% from 2011 to 2020. But in the pandemic’s first year, that fraction soared to 39.7%, the study found.

“I was not surprised that the obesity rates went up, and I was not surprised that they went up above baseline. That was the trajectory with COVID-19," said Dr. Robert Siegel, the study’s author. "I was surprised by how much it went up. That was pretty striking.”

Siegel presented his findings last week at the annual conference of the professional group the Obesity Society. The research offered another glimpse of the broader health impact of the pandemic across the Cincinnati region and the nation.

Siegel said he plans on deeper analyses of his results. But he said that, as with adults during the pandemic, children were much more sedentary, confined to computers for hours. Many lost access to healthy breakfasts and lunches when schools closed.

The pandemic also worsened mental health problems such as anxiety and depression, which can trigger weight gain. Economic hardship “made it hard at times to get good food even if you could afford it,” Siegel said.

Obesity in the United States has been rising for decades, which affects rates of diabetes, heart disease, cancer and a host of other ailments, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Through the pandemic, research has found obesity and diabetes put COVID-19 patients at higher risk for hospitalization and death.

An adult is considered obese when the ratio between weight and height is higher than 25. But in children, that ratio, called the body mass index, is measured as a range. Siegel’s research found that more children are moving into percentiles ranges of obesity.

The Cincinnati Children’s study started in 2011 and recorded information from 2,459,554 encounters.

Controlling obesity is more than a person’s intake and outflow of calories, Siegel said, and could include better food labeling, taxes on unhealthy foods such as sugary drinks and limitations on advertising.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Cincinnati Children's study finds children picked up the pandemic pounds, too