How a Cincinnati physician helped uncover our prehistoric past

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

These days, we can go to the Museum of Natural History & Science at the Cincinnati Museum Center to see Ice Age fossils and recreations of life in this region before recorded history. But in the early days of Cincinnati, such information was not yet discovered.

Dr. Daniel Drake, the physician who founded the Medical College of Ohio in 1819, was also Cincinnati’s first historian.

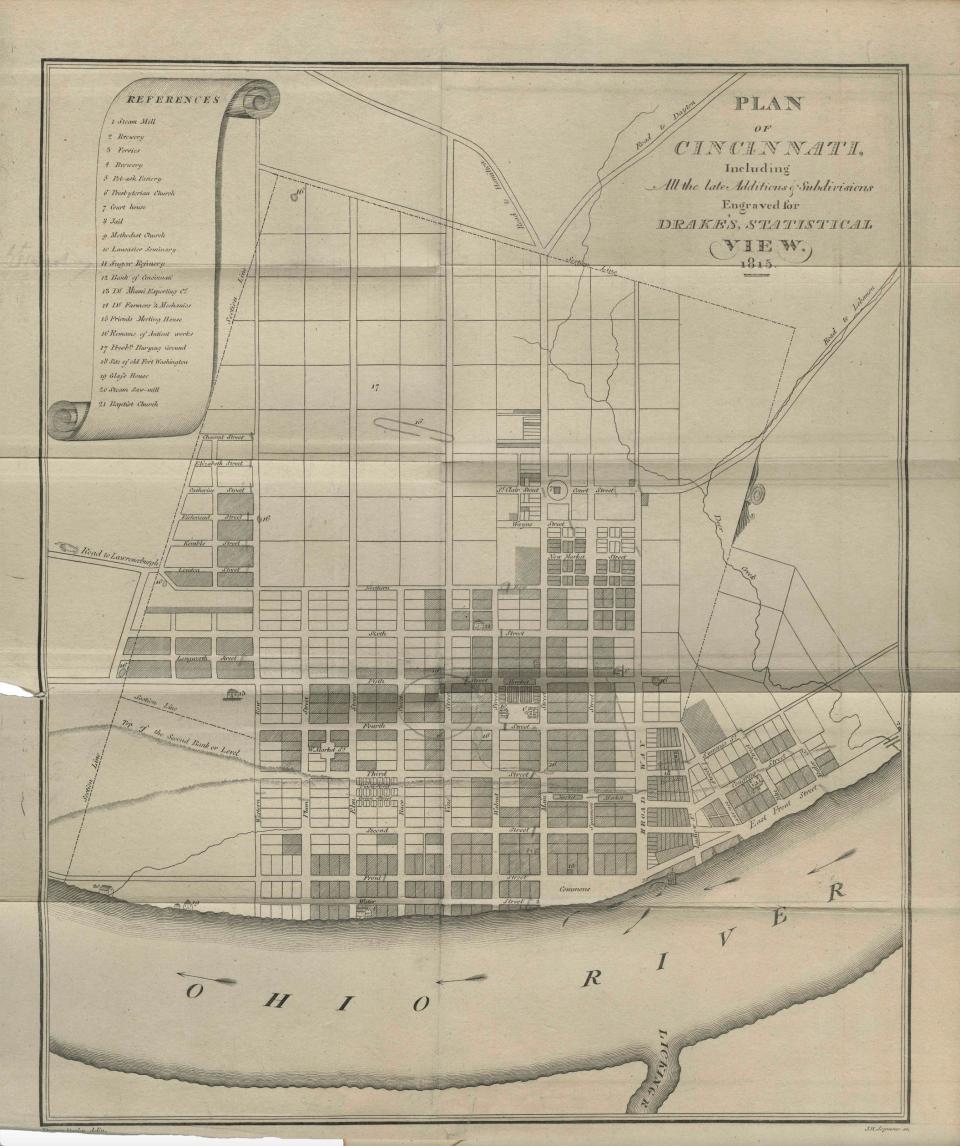

His book, “Natural and Statistical View, or Picture of Cincinnati and the Miami Country,” published in 1815, reported the state of the young city 27 years after the first settlers had arrived, including the history, geography, statistics, weather and botany of the area.

“The relations of a town with the surrounding country, are an essential part of its history, and cannot be understood without studying both,” Drake wrote.

Ice Age fossils at Big Bone Lick

His chapter on the physical topography gives insight on what was understood at the time about the prehistory of the region. After all, it is the geological events that forged the Ohio River and formed Cincinnati’s signature hills and the basin plateau that have determined the development of the city.

He reported that fossils of mammoths and mastodons, which roamed North America until 10,000 years ago, were found near the Big Bone Lick in Union, Kentucky. The warm salt springs had been an inviting place for Ice Age animals to drink.

Big Bone Lick is considered the birthplace of American vertebrate paleontology. In 1807, President Thomas Jefferson sent Gen. William Clark, of the famous Lewis and Clark expedition, to collect fossils from Big Bone Lick for study.

Drake wrote that Dr. William Goforth, under whom he had studied medicine, had collected wagonloads of bones from the site in 1802-03, including “the remains of no less than six nondescript quadrupeds, most of them gigantic! … Among the rest, some of the bones of the rhinoceros were thought to be ascertained.” (There was an extinct rhinoceros, known as teleoceras, that grazed across North American until about 4.5 million years ago.) Unfortunately, the bones were loaned to a swindler who shipped them to Europe for exhibition and the samples were lost.

Reformed by glaciers

Drake described the geological strata of the area: limestone, alluvium (silt deposited by running water), clay, loam and “primitive rocks.” At the time, scientists did not know how these different geological strata came to be in this area. “The mighty operation which transported into this country, these numerous masses, is entirely unknown,” Drake wrote.

Someone suggested they were “thrown thither by volcanoes,” but Drake noted the country contains no volcanoes or craters. Another remarked “that masses of stone are sometimes transported by cakes of ice, in which they happen to be imbedded,” which was the theory Drake preferred.

And that is what happened.

About 2 million years ago, the ancient Teays River ran north and west across what is now the Midwest, from North Carolina through Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, crossing Ohio at about Chillicothe.

Three major glacier formations during the Pleistocene Ice Age drastically altered the landscape. The Pre-Illinoian glacier (1.2 million years ago) advanced from the north, stopped near Northern Kentucky, then retreated. The glacier destroyed the Teays River by creating a massive dam, which diverted water into lakes that overflowed into streams that drained into the Mississippi River. This was the early formation of the Ohio River.

Then, the Illinoian glacier (300,000 years ago) and Wisconsinan glacier (70,000 years ago) left deposits in the area that created rock shelves and the hills and basin where Cincinnati lies.

None of this was known by Drake and his contemporaries. Glacial theories began to emerge in the 1830s, and Louis Agassiz and others proposed the theory of the Ice Age in 1837. It took decades before the theories were accepted by the scientific community. It is fairly remarkable that Drake could discern as much information as he did at the time.

Ancient burial mounds in Cincinnati

Drake also devoted a chapter to “antiquities,” the relics of the ancient people who once lived there, particularly the burial mounds in the Cincinnati basin that have long-since been obliterated. Many of the mounds were still around in 1815. Drake described them and marked them on a map included in the book.

“The principal wall or embankment, encloses an entire block of lots and some fractions,” Drake wrote about the largest mound in the center of the city. “It is a very broad ellipsis; one diameter extending 800 feet east from Race-street; and the other about 660 feet south from Fifth-street. … On the east side it had an opening nearly 90 feet in width. It is composed of loam, and exhibits, upon being excavated, quite a homogenous appearance. Its height is scarcely three feet, upon a base of more than thirty. There is no ditch on either side. Within the wall, the surface of the ground is somewhat uneven or waving; but nothing is found that indicates manual labor.”

That site today includes Fountain Square, Carew Tower and the Westin Hotel.

Other earthworks and embankments were scatted throughout the downtown basin:

A mound at Fourth and Walnut with a wall connecting to a smaller mound at Third and Main streets;

A mound on Fifth Street east of Broadway;

A mound at Fifth and Mound streets;

A mound at Mound Street and Northern Row (Seventh Street);

A mound at Richmond Street and Western Row (Central Avenue);

Convex earthen banks between Vine and Elm streets near present-day 12th Street.

Drake reported other “inequalities of surface” that were not natural, but had been reduced and obscured by 1815. Gen. William Henry Harrison, the future president, had examined those features in an excursion with Gen. Anthony Wayne in August 1793, and spoke of his observations in an address to the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio in 1837:

“When I first saw the upper plain on which that city stands, it was literally covered with low lines of embankments. … Many so faint, indeed, as scarcely to be followed, and often for a considerable distance entirely obliterated, but by careful examination, and following the direction, they could again be found.”

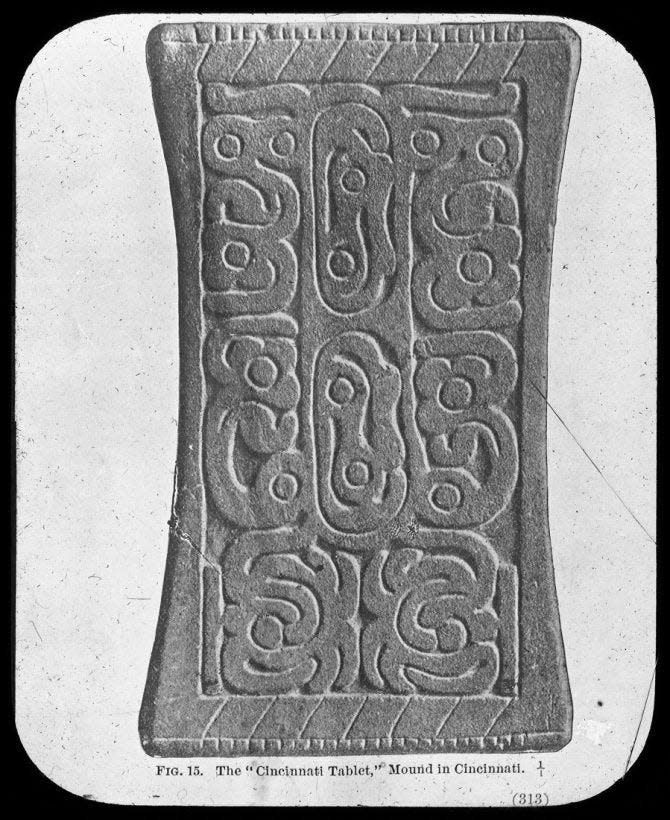

The ‘Cincinnati Tablet’ found

The tallest mound was the one at Fifth and Mound streets, also the source of the street’s name. In 1815, Drake reported it was 27 feet high, but that eight feet had previously been cut off by Wayne in 1794, when he commanded Fort Washington, to prepare the mound for use as a sentinel.

In 1841, Mound Street was regraded and the mound was almost entirely cut away. Workmen found several skeletons near the surface, but the most significant archeological find was deeper down. Under the skull of a decayed skeleton was found a stone tablet that became known as the “Cincinnati Tablet.”

The 5-by-3-inch sandstone tablet was carved with designs or figures, which has led to endless speculation about its purpose, from monitoring the sun and moon at certain times to using it to create tattoos. No one knows.

The “Cincinnati Tablet” was widely reported and studied at the time, but 30 years later its authenticity was questioned, leading some people to dismiss it as a hoax. Cincinnati publisher Robert Clarke wrote extensively in defense of the tablet in his 1876 book, “The Pre-Historic Remains Which Were Found on the Site of the City of Cincinnati, Ohio, with a Vindication of the ‘Cincinnati Tablet.’” Since then, it has been accepted as authentic.

It was the first of 13 such tablets discovered in Ohio, Kentucky and West Virginia that are identified with the Adena culture in southern Ohio during the Early Woodland Period (1000-200 BC). Not much is known about the mound builders, who are credited with numerous burial earthworks, most famously the Serpent Mound in Adams County.

None of the Adena burial mounds in Cincinnati remain. The Mound Street site where the tablet was found is now a UPS warehouse on Gest Street. The tablet had been kept by Joseph Gest, the city engineer who oversaw the grading project. His son, Erasmus Gest, donated the relic to the Cincinnati Historical Society.

Out of respect to the native peoples from the region, the Cincinnati Museum Center no longer displays the “Cincinnati Tablet” or other native sacred objects.

Additional sources: “Ancient Metropolis: Prehistoric Cincinnati” by Terry A. Barnhart, Cincinnati Museum Center, Cincinnati & Hamilton County Public Library, Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Ohio History Central, Cincinnati Curiosities, Northern Kentucky Tribune, Live Science.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: How Cincinnati’s prehistoric fossils were found