Cincinnati Southern Railway controversies date back to beginning of railroad's history

It's been easy of late to start an argument over whether Cincinnati should sell its railway.

Controversy, it turns out, is as old as the railway itself.

“There were frequent debates ... to complete the railroad,” said Cincinnati attorney Tim Burke, author of a 1977 history of the Cincinnati Southern Railway. “It could have ended up like the subway.”

It didn’t, of course, instead now marking its 143rd year of operation. On Tuesday, Cincinnati voters will decide whether they want to sell the line to Norfolk Southern for about $1.6 billion.

Rail replaces steamboat transport

In many respects, Cincinnati Southern was born from controversy.

With its thriving steamboat industry, Cincinnati had become one of the largest cities west of the Allegheny Mountains by the middle of the 1800s, with trading partners to the West and the South.

The rise of train travel reversed the city’s fortunes.

“Without adequate rail ties to the South, Cincinnati was put in an extremely poor financial position,” Burke wrote in his history, created as a memo in a 1977 Cincinnati Southern lawsuit against the city of Cincinnati.

The Civil War, 1861-65, had compounded the troubles.

“One of the first effects of the war was to completely stagnate the city commercially and industrially,” Burke wrote, quoting a 1922 history by University of Georgia history professor Ellis M. Coulter. "Her Southern markets slipped almost overnight."

'Remarkable proposition' leads to Cincinnati Southern

The city had been in search of solutions.

In 1835, it hosted a public meeting to consider rail connections between Cincinnati and the South. The next year, a city delegation traveled to a rail convention to explore prospects.

A nationwide financial crisis in 1837 slowed efforts. So did an 1851 change in the Ohio constitution, which banned cities from owning stock. That had been an early strategy to get into the rail business.

In 1859, city efforts to raise $1 million in private funds to establish a route to Knoxville stalled. A similar attempt in 1866 also failed.

During the war, Cincinnati was considered for a stop on a military railway to the South – but the initiative was abandoned for other war priorities.

A solution – soon dubbed “the remarkable proposition” – came from Ohio Sen. Edward A. Ferguson: Cincinnati should build and own its own railway.

Ferguson’s proposal became law in May 1869. The next month, Cincinnati City Council endorsed it as “essential to the interests of the city,” selected Cincinnati Southern as the line’s name and named Chattanooga as the southern end of the route.

That June, voters OK’d funding the railway. A city superior court, per Ferguson’s bill, then appointed a five-member board of trustees to move forward.

Finances, contracts both contentious

Controversies soon resurfaced.

Kentucky and Tennessee lawmakers dragged out needed approvals of the line, irritated by what they saw as Cincinnati’s power play.

During a 1873 national financial crisis, “trustees were publicly advised to abandon the entire work,” Burke’s memo said, citing an 1894 history by Johns Hopkins University historian J.H. Hollander. Instead, they delayed a bond deal to finance the railway and raised the first $5,000 on personal credit.

The bond financing followed, as did more controversy. Billed as a $10 million project, the price tag ballooned to $18 million between 1875 to 1878, prompting the Enquirer to dub it “our white elephant.”

Early agreements with operators – which would actually put trains on Cincinnati Southern tracks – were also problematic. The first lease lasted less than a year, the second for two years.

And while the third agreement – with Cincinnati New Orleans & Texas Pacific Railway, a unit of Norfolk Southern – has been in place since 1881, it’s not always been smooth sailing.

Nine years in, CNO&TP came under the control of another operator which was in the hands of a receiver to oversee its finances. CNO&TP soon found itself in the same situation following a fraudulent stock deal on its part.

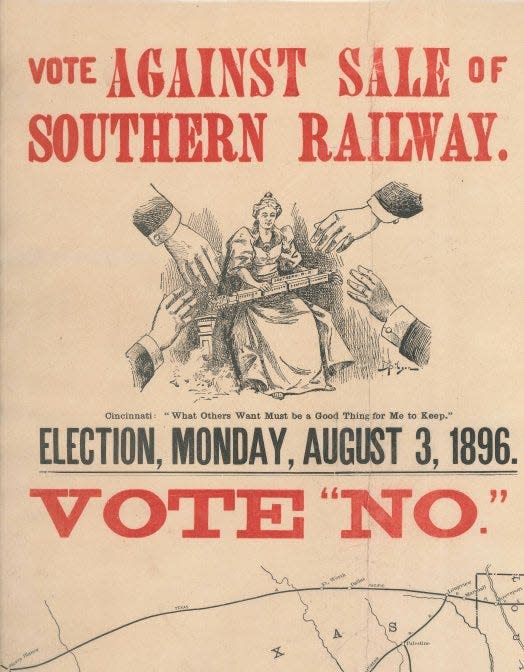

In 1896, Cincinnati Southern and its operator survived something of a hostile takeover attempt. Put to a vote, Cincinnatians turned down Southwestern Construction Co.’s offer to buy the railway by just 338 votes.

History by 'kid lawyer' lives on

Tim Burke wrote his 77-page Cincinnati Southern history – with 11 pages devoted to footnotes – during a temporary assignment for a Cincinnati lawyer named Robert E. Manley.

“I was a kid lawyer,” he said. “It was a six-week contract.”

Now president of the Manley Burke law firm, Burke traveled the 337 miles of the Cincinnati Southern line, from Cincinnati to Chattanooga, to research the railway. Along the way, he visited museums and historical societies, collecting legal documents, testimony, books and newspaper articles to compile his memo.

The document lives on as a link on the Cincinnati Southern website. More recently, Burke has sent it "to folks on both sides of the current issue."

He's not sure it made much of a splash in 1977. “I doubt the judge even read it,” he said.

But the suit itself explored another still-relevant Cincinnati Southern controversy – the selection of its board of trustees.

Manley filed it on behalf of Republican trustees, opposed to a then-new state law shifting the duty of appointing trustees to Cincinnati’s mayor. That had been the job of a city superior court and, when that went away, the Hamilton County Common Pleas Court’s probate division.

The new law, Burke wrote in his memo, was “not the first attack to have been made on the board of trustees.”

Critics said the original trustees lacked practical experience in railway construction. They also found fault in what were essentially lifetime appointments.

The mayor’s office addressed the latter concern, establishing five-year terms, but without term limits. (At present, trustees Mark Mallory, Amy Murray and Paul Muething are in their first terms, with Charlie Luken appointed to a second term in January. Paul Sylvester, current treasurer, has served since 1984.)

The mayor’s office also eliminated pay for trustees.

Rents rise from $1 million to at least $20 million a year

Today, opponents of the city’s call to sell Cincinnati Southern are concerned proceeds of the sale won’t be managed well.Ohio lawmakers shared those concerns early on, putting safeguards in place to ensure fair leasing and steady income. As a result, CNO&TP agreed to long leases with rising rates:

It paid $25.2 million to Cincinnati Southern over its first 25-year contract.

It agreed to pay a total of $67 million between 1902 and 1966.

It agreed to new terms in 1928, under a 99-year lease that would have paid Cincinnati Southern close to $146 million in rent through 2026, plus some of its annual profits.

In 1987, under its current contract, it agreed to pay $11 million a year in rent, with an escalation clause tied to the gross national product. That put its rent at $24.3 million for 2022 and its total rent payments since 1987 at $633.6 million.

Burke, a stalwart of the Hamilton County Democratic Party who ended a 25-year term as its chair in 2018, celebrated those financial results when he helped sue the city.

“The Cincinnati Southern Railway has proven to be the city’s greatest money maker,” he concluded in the rail history memo. “Its return on investment, dollar for dollar, is unmatched.”

He supports selling Cincinnati Southern now, he wrote in an August guest column for the Enquirer, because the proceeds would be placed in a “lock box trust” with only limited interest income available to spend on city infrastructure projects.

“Funds in the trust,” he said, “would continue perpetually.”

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Why has the Cincinnati Southern Railway been controversial?