Cincinnati's forgotten women’s suffrage heroes: Lucy Stone, Margaret Longley and Cornelia Cassady Davis

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

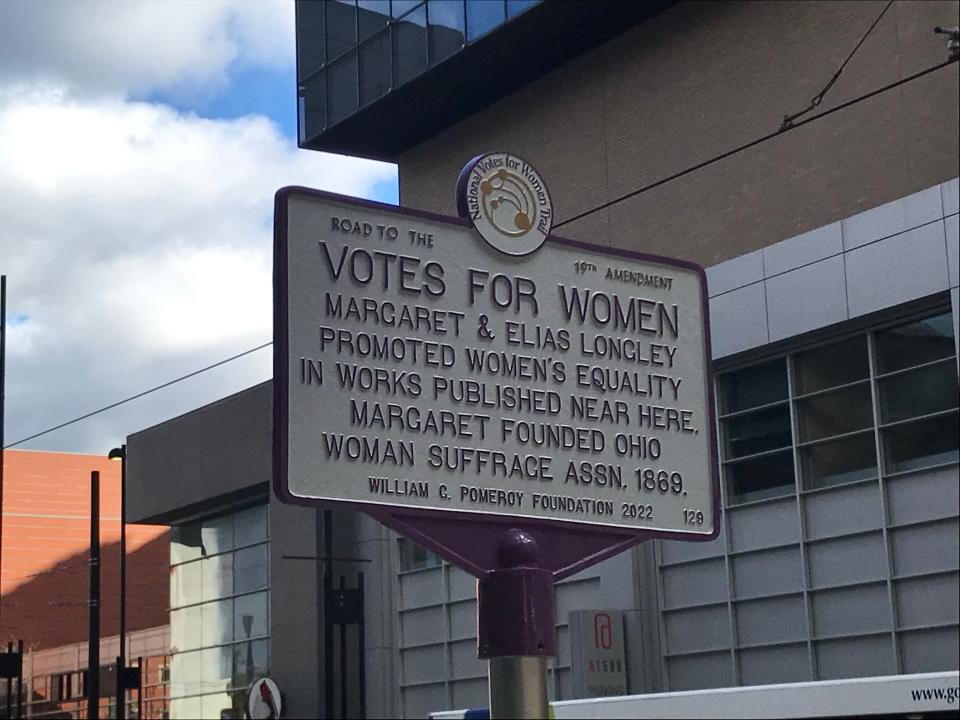

Three new historical markers in Cincinnati should draw attention to some lesser-known stories of the local women who helped win the right to vote just over a century ago.

They are among 250 markers nationwide along the National Votes for Women Trail, sponsored by the National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites (NCWHS) and the William G. Pomeroy Foundation, that recognize and honor the work of the thousands of women who contributed to the suffrage movement.

It took more than 70 years of campaigning for women to reach the voting booth, from the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 to the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

“When it comes to women’s rights and suffrage in the early days of the movement, there are so many women who have been forgotten and that we need to bring back. We need to remember them,” Cincinnati Vice Mayor Jan-Michele Lemon Kearney said at the marker dedication, held at Fifth Third Center on March 25.

10 _ Women: These women have been written out of history books. This project is putting them back in.

The Cincinnati markers honor suffragist Lucy Stone and her husband, Henry Blackwell (located at 2900 Gilbert Ave., Walnut Hills, near the Giminetti Baking Company); journalist and teacher Margaret V. Longley and her husband, Elias (on Walnut Street between Fifth and Sixth, Downtown); and artist Cornelia Cassady Davis (at the top of the Elsinore steps near the Cincinnati Art Museum, Eden Park).

Presenters repeatedly made note that “Ohio played a crucial yet forgotten role in the fight for women’s suffrage,” as well as the push for equal rights and the abolition of slavery.

“We may not know this from our history lessons in school, but we’re going to have to add this to our history books,” Lemon Kearney said.

‘Untapped, inspiring stories’

Local researcher Katherine Durack, a retired faculty member from Miami University, did the initial deep-dive research about these women that pulled them from the dust of history.

“It seemed to me that noise wasn’t happening (leading up to) the women’s suffrage centennial. So, I started rattling cages, contacting people,” she said. “I originally thought that, well, I’ll find the person who knows the Ohio history and that will be great, and I never found that person. Along the way, I just got so wrapped up and entranced by the stories that we have to tell in Cincinnati but also throughout the state.”

There are several slim volumes about the history of women’s suffrage in Ohio, she said, but something was needed to draw more attention to it.

“What I found is that there’s this rich wealth of untapped, inspiring stories of people who literally dedicated their entire lives to this cause,” she said.

Durack documented about 30 Ohio locations pertinent to the suffrage movement on a Google map, which she shared with NCWHS. They chose to add markers to three of those sites in Cincinnati for the trail. The markers serve as an introduction, to pique your curiosity to know more.

Equality in marriage

“Back in the day, they’d call me a Lucy Stoner,” Christina Hartlieb, executive director of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, told the crowd at the marker dedication. “That’s what women in the late 1800s were referred to when they kept their birth surname even after marriage.”

Lucy Stone and her husband, Henry Blackwell, were among the top tier of suffragists and abolitionists. She helped organize national conventions for women’s rights throughout the 1850s. The Blackwell family lived two blocks from Harriet Beecher Stowe. Henry’s sister, Elizabeth Blackwell, was the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States.

Hartlieb said that the marriage of Lucy and her husband was “markedly unconventional for the era.” They signed a prenuptial agreement that described “how Lucy would retain her surname, retain her own money and retain the, uh, control of procreation,” Hartlieb said.

The couple, who met in 1850 at his hardware store – Coombs, Ryland and Blackwell’s on Main Street in Cincinnati – were collaborators and activists. Together, they led the American Women’s Suffrage Association and edited the Women’s Journal. They both spoke at the eighth National Women’s Rights Convention, which was held in Cincinnati at Smith & Nixon’s Hall on West Fourth Street, Oct. 17-18, 1855.

When a heckler at the convention called the female speakers “a few disappointed women,” Lucy Stone replied with one of her most notable speeches, agreeing that she was “a disappointed woman.” “In education, in marriage, in religion, in everything, disappointment is the lot of woman. It shall be the business of my life to deepen this disappointment in every woman’s heart until she bows down to it no longer.”

Lessons in touch typing and women’s rights

Margaret Longley and her husband, Elias, were both journalists and teachers that focused on their particular passions – shorthand and typewriting. They published the Phonetic Magazine and a newspaper called Type of the Times out of their offices in the Apollo Building, formerly at the northwest corner of Fifth and Walnut streets.

In addition to information and lessons, they also printed articles advocating for abolition, equal rights and women’s suffrage in their publications.

Elias was a reporter for the Cincinnati Commercial and Cincinnati Gazette and did shorthand reporting of Abraham Lincoln’s speech at the Burnet House in 1861 and Civil War-era court reporting.

Margaret challenged restrictions on women’s roles in society in the 19th century. She learned typesetting, one of the few skilled jobs available to women in printing, but rose from there. She served as editor of Woman’s Advocate magazine and as court reporter for Cincinnati Tagliche Abend-Post, a German-language newspaper.

In 1882, she founded her own school, Longley’s Shorthand and Typewriting Institute, and published a typing manual, “Type-Writer Lessons, for the Use of Teachers and Learners, Adapted to Remington’s Perfected Type-Writers.” The book introduced her innovation of eight-finger typing and using the thumb for the space bar, which is known as touch typing, on the QWERTY keyboard.

Among the practice phrases she included in her typing manual were such subversive lines as “no man can take her place” and “women’s right to the ballot.”

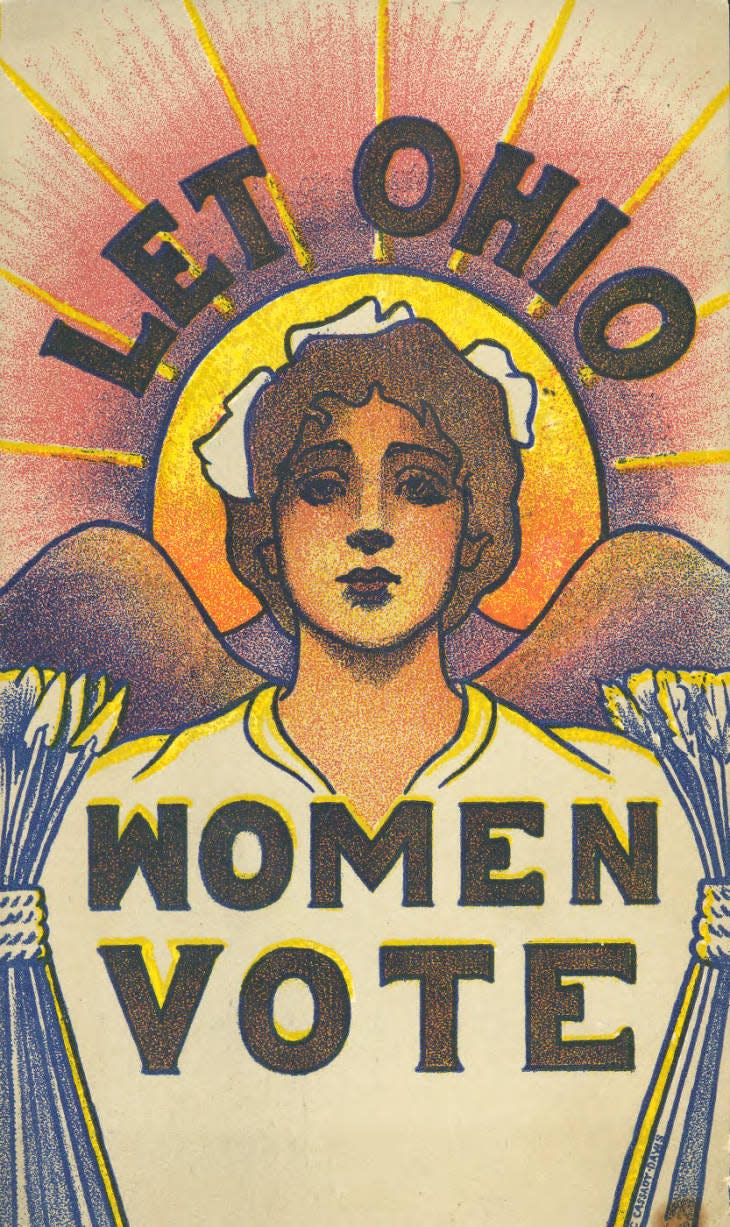

‘Let Ohio Women Vote’

Cornelia Cassady Davis was an artist trained at the Art Academy of Cincinnati, where she studied under Frank Duveneck. Her paintings were exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. She was known for her paintings depicting Navajo and Hopi people in New Mexico and Arizona.

Davis was a member of the Woman’s Art Club in Cincinnati, along with artists Dixie Selden and Elizabeth Nourse, and in 1913 became the first woman admitted to attend the life class (figure drawing) in the all-male Cincinnati Art Club.

It would take another 66 years before women were offered membership in the club.

Notably, Davis created the iconic “Let Ohio Women Vote” poster used by the Ohio Woman Suffrage Association for the 1912 campaign to get a state constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage.

The image, which incorporates the sun, hills and wheat elements of the Ohio state emblem, is well known, but despite her name on the bottom of the poster, the artist is rarely recognized for her contribution.

That changes with the National Votes for Women Trail marker.

“A lot of this history I didn’t know. So there’s much that would be forgotten but for having markers like this,” Lemon Kearney said.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: National Votes for Women Trail markers honor Cincinnati suffragists