Circuit court bench in South Dakota struggles to diversify

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Less than half the people in state prisons in South Dakota are people of color, but none of the judges who sent them there are.

The general election Nov. 8 did not change that.

Circuit judges in South Dakota, who preside over the felony criminal cases that can send a defendant to prison, come up for election every eight years. Magistrate judges, who handle misdemeanor cases, are appointed.

Most judges never run in a contested election. Only one sitting circuit judge faced a challenge in 2022. Seven other candidates vyied for two open seats.

The vast majority of the circuit judges on those uncontested ballots are initially appointed by the governor, based on the recommendations of the Judicial Qualifications Commission (JQC). The demographic makeup of the bench, in other words, is more a reflection of applicants and gubernatorial discretion than citizen support.

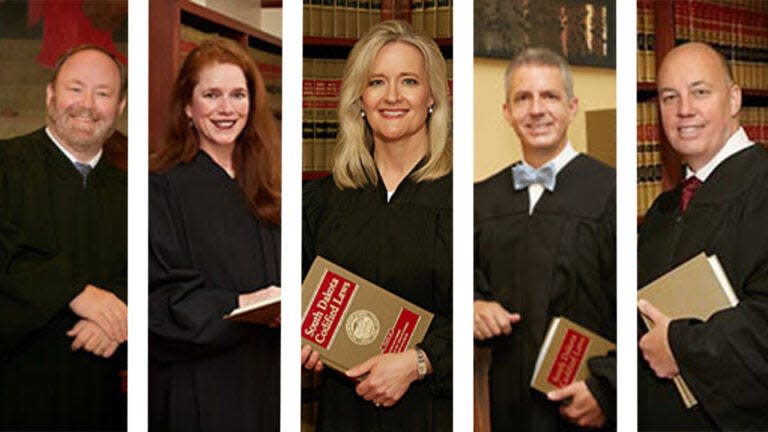

Gov. Kristi Noem and her predecessor, Gov. Dennis Daugaard, have each made an impact on gender representation in recent years. About 40% of the state’s 44 circuit judges are female. In the Sixth Circuit, every judge is female. The Second Circuit – the state’s largest with 13 circuit judges – is majority female, and is led by a woman, Presiding Judge Robin Houwman.

Four of Noem’s seven appointments have been female. Three were to the Sixth Circuit bench in the Pierre area. She also appointed a woman to the South Dakota Supreme Court, Justice Patricia Devaney.

More:Lack of diverse interpreters creates delays in due process for some Minnehaha County defendants

“As the first female governor of South Dakota, Gov. Noem is immensely proud of the significant increase in the number of women on the bench,” spokesperson Tony Mangan wrote. “The governor closely reviews the qualifications of all candidates and her judicial appointments are made on merit.”

Mangan did not address racial or ethnic diversity directly in the statement, saying only that the governor’s goal “is to select the best qualified person who will carry out their duties as prescribed by statute.”

Lack of diverse candidates

About half of South Dakotans are female, putting gender diversity on the bench within 10 percentage points of reflecting the state’s demographic makeup.

The growth in female representation has been significant since State Bar President Lisa Marso began her career three decades ago. There are now two women on the South Dakota Supreme Court.

“When I started, there were no females on the state Supreme Court,” Marso said.

In terms of racial diversity, however, South Dakota’s bench is much further off. The South Dakota Unified Judicial System does not track the race or ethnicity of circuit court judges, but interviews with multiple sources familiar with the state court’s makeup and its history suggest that no people of color have ascended to the circuit bench.

“I have never known a person of color who has served as a circuit judge or South Dakota Supreme Court Justice,” said Roger Baron, professor emeritus at the University of South Dakota Law School. “I can think of none who have been sworn into the position during my time in South Dakota, which dates back to 1990. And, I can think of no such judgeships that I have run across historically.”

As of 2021, the state had an estimated 9% Native American population, with another 4.6% of people identifying as Hispanic and 2.5% identifying as Black. Just one judge on the magistrate side of state court, Andrew Robertson, is an enrolled tribal member. Magistrate judges handle misdemeanor cases, small claims and a variety of other issues.

Judges on the federal bench in South Dakota are appointed by the White House. There are no people of color on the federal side in the state, according to the Federal Judicial Center.

The lack of diversity on the bench is, in part, a measure of a lack of diverse candidates, according to USD Law School Dean Neil Fulton.

The law school has worked to advance diversity, Fulton said. The 87-member class of 2025 has 12.5 students who self-identified as a person of color. The incoming class the year before was 15% people of color and 60% female.

It will take time for those candidates to work their way into a position where they’d feel ready to apply for a judgeship, Fulton said.

“I know some really talented young lawyers of color, but they are really young,” he said. “But if you look at the bench, lawyers often land there later on in their careers.”

Fulton and Marso hope outreach to younger people, including visits to high schools and student tours of the law school for low-income and minority students, will help move the needle as time passes.

Juarez: ‘I do feel a sense of obligation’

One of the talented young lawyers Fulton referenced is Cesar Juarez. He works in private practice in Sioux Falls for Lynn Jackson and chairs the Bar’s diversity committee. The Mexico native moved to South Sioux City, Nebraska, as a teenager, learned English, then went on to study and play soccer at Mount Marty University.

Juarez said his choice to enroll in law school at USD was motivated in part by a desire to serve Spanish speakers in a legal system designed for English speakers. He and his wife initially planned to move to California after his graduation, but Juarez found himself wondering, “am I taking the easy way out?”

Spanish speakers in South Dakota have far fewer options for legal counsel than they do on the coasts.

“If I went to law school thinking I wanted to help people who speak Spanish, am I running away from an opportunity to help people who really need the help?” Juarez said. “I do feel a sense of obligation to help folks who are not well represented.”

Ideally, Juarez said, the judiciary in the state would reflect its population. The Bar membership would, as well. It’s an issue that’s “near and dear to my heart,” he said, particularly as the state’s Hispanic population has grown to more than 41,000 – a 75% jump since 2010.

That growing population keeps Juarez plenty busy.

“Everybody assumes that I like the fact that I’m one of probably a handful of lawyers in the entire state that are Hispanic,” he said. “I actually don’t like that at all. It’s an immense amount of pressure, because I get a ton of phone calls with people that I cannot help.”

Juarez has great respect for the position of judge, he said, and doesn’t feel he’s prepared for the role just yet. But he also worries about what would happen to his clients if he stepped away from private practice.

More:Data shows Native Americans in South Dakota receive longer manslaughter sentences

“The moment I do that, I won’t be able to help,” Juarez said.

On the other hand, he said, it can be difficult for his clients to believe they’re getting a fair hearing in a state with an all-white circuit bench.

“I do think we have some really great judges, but when you’re a person of color who has to go in front of these judges, it is definitely something you’ll think about,” Juarez said. “If the judge doesn’t look like you, cannot relate to your upbringing, it’s something that weighs on you.”

Means: State not welcoming

Tatewin Means, of Porcupine, has also pondered the question of how and where to do the most good. Means is a lawyer and member of the Sisseton Wahpeton, Oglala Lakota and Ihanktonwan nations.

Means has served as the attorney general for the Oglala tribe, and lost a 2018 primary bid to be the Democratic nominee for South Dakota attorney general. She is now the executive director of the Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation in Oglala Lakota County.

Friends and colleagues have suggested that Means pursue a judgeship in state or federal court, but she feels that her work in Porcupine lets her do more good. The historic and contemporary racial disparities in the justice system, Means said, would be difficult to address from within.

“The needs in our communities are so great that if there’s a choice between working in our communities or working in a really archaic justice system that hasn’t served the needs of our people, that is an institution that has racist roots … why would we want to put ourselves in those positions and just be frustrated, because you’re working within a bureaucracy?” she said.

The state as a whole has an issue with being welcoming to people of color, Means said. She pointed to the Grand Gateway Hotel and Cheers Sports Lounge in Rapid City as an example of continuing issues. The U.S. Department of Justice sued the establishment in early October for allegedly denying service to Native Americans after a Facebook post announcing that Native Americans were “no longer welcome.” The lawsuit came six months after the nonprofit NDN Collective filed a lawsuit of its own.

Situations like those don’t help with recruitment of lawyers or judges, she said.

“When you hear about these things that are happening here with no real ramifications, why would anyone of color let alone our own people want to come and practice law here? Because it seems so insurmountable,” she said.

Volesky: Perception is important

Ron Volesky is a tribal member who’s sought to surmount the odds in South Dakota.

The Huron attorney and former legislator tried for years to land a spot on the circuit court bench. The enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe also applied for an appointment to the South Dakota Supreme Court.

“Obviously, I am a proud person and I believe in my abilities, but if they felt that I didn’t have the background or the experience or whatever, I respect their opinion,” Volesky said. “I struck out every time, and I’ll put that blame on me.”

Volesky sees the lack of representation as a problem of perception. He believes South Dakota judges are generally fair in their treatment of defendants, but that the lack of familiar-looking faces on the bench – alongside an out-sized population of minorities in prison – has an impact on faith in the system.

More:A guide to voter rights in South Dakota. What you need to know before you cast a ballot

“We need to make a real effort to get qualified Native Americans into these positions in the judiciary, and those bodies that affect the judiciary, because Native people, whether we want to say it or not, are really invested in the system,” Volesky said.

It’s also a matter of historical precedent in a state with a storied history of Native American leaders. Volesky was an aide to South Dakota icon Ben Reifel, the first Lakota member of the U.S. Congress, and laments the fact that there are no leaders like him to point to in the judiciary.

“We can elect Ben Reifel to Congress, and we can elect me to the Legislature for 16 years from a non-Indian district, but we can’t seem to get a Native American on the Supreme Court or the circuit court in the state of South Dakota,” he said.

Robertson: Outreach, education can help

Representation is important to Judge Andrew Robertson, an enrolled member of the Sisseton- Wahpeton Oyate, but it wasn’t top of mind when he put in an application to become a magistrate judge. The former deputy public defender and longtime Sioux Falls resident said he looked at the position as a way to advance his public service. His father was a lawyer who also served as diocesan bishop of the Episcopal Church in South Dakota. His mother was a teacher at Whittier Middle School.

The relevance of his appointment wasn’t lost on him. USD Law Professor Frank Pommersheim was the first to point out that Robertson was likely the only enrolled tribal member serving as a magistrate judge in the state.

“I don’t necessarily like to highlight it a lot,” Robertson said. “I’m just an everyday person, just like the rest of the folks in the community. But it certainly is a neat thing to see happening at this point in South Dakota.”

Opening doors as a public servant also aligns with Robertson’s family history. When his father graduated from law school in 1976, he was one of just a handful of Native American attorneys in the state. He was later the first Native American bishop for the Episcopal Diocese.

Judge Robertson expects that the circuit bench will change over time, but that it will take a lot more outreach to send the message to young people that a legal career and even service from the bench are viable options.

“When you look at the bigger picture, it’s something we’ve been working on since the ’70s,” he said. “It’s one of those things where you just keep kind of pushing in every corner, and I think eventually it starts to snowball.”

This article originally appeared on Sioux Falls Argus Leader: Circuit court bench in South Dakota struggles to diversify