As The Citadel confronts racist past, a Black cadet shares his truth through fiction

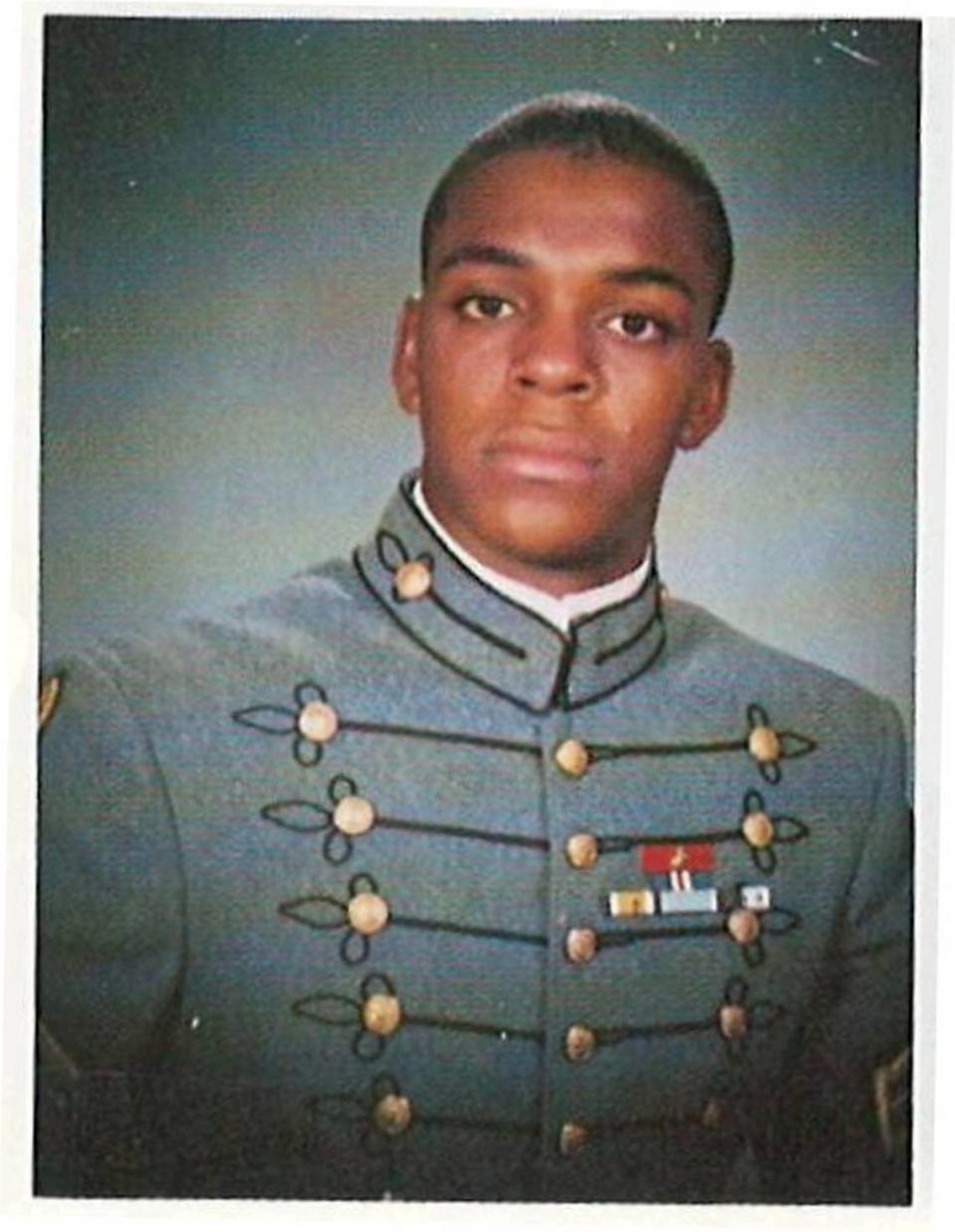

Ken Gordon never kept a journal during his time at The Citadel. But no one, he explained more than 35 years later, can forget hell.

When Gordon reported to the Charleston campus in August 1984, he found a South that refused to let go of its past. Confederate battle flags waved in the stands during home football games. Cadets marched to “Dixie” during Friday afternoon parades.

Eighteen years had passed since Charles DeLesline Foster broke the color barrier in 1966 to become the first African American to join the Corps of Cadets. Yet Gordon, an 18-year-old Black freshman from Willingboro, New Jersey, remembers being called one name more than any other his first year: The n-word.

“The frequency for which I was called that name, the frequency for which they referred to my race in that way in front of me as if I was not even there — as if I did not even matter. There was no shame,” Gordon said. “There was no guardedness. There was no hesitation.”

His parents had urged him not to go to The Citadel, but Gordon’s determination prevailed. He dreamed of flying jets. Upon graduation, Gordon could enlist as an officer — a must if he hoped to become an Air Force pilot.

Instead, he graduated in 1988 with two stomach ulcers and four years of trauma.

“I know I am not the only one who saw things, who heard things, who went through things. I know we all did. So why did Pat Conroy have to be the first to write about something that happened to someone who looked like us?” Gordon said.

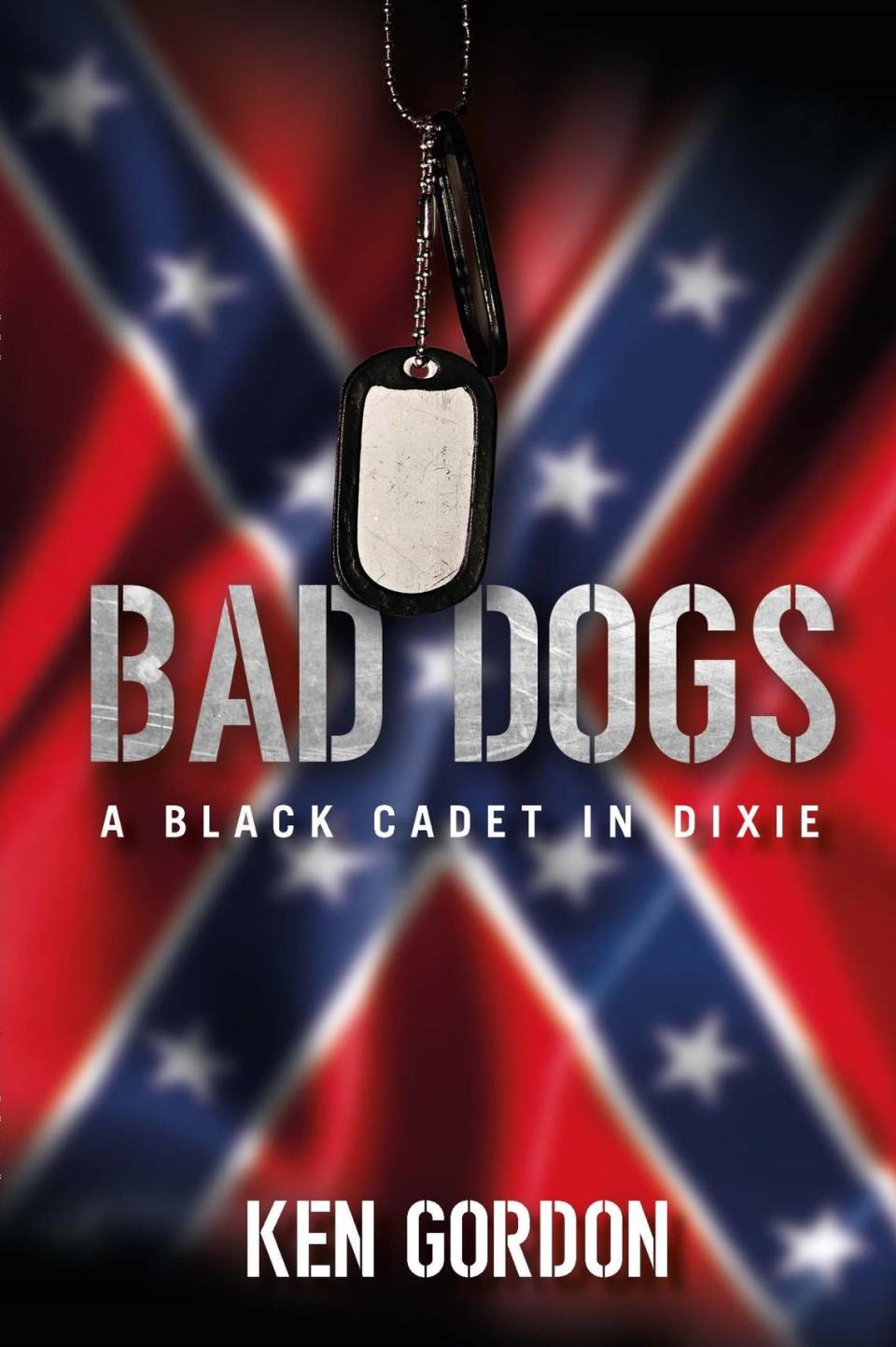

In December, Gordon published his novel, “Bad Dogs: A Black Cadet in Dixie.” It joins a unique collection of books inspired wholly or partly by what happens behind The Citadel’s iron gates, including Conroy’s “Lords of Discipline” and U.S. Rep. Nancy Mace’s first-person account of gender integration of the Corps, aptly named, “In the Company of Men.”

Gordon’s book, however, is the first known work — fiction or otherwise — written by a Black cadet about their Citadel experience.

“’Bad Dogs’ is all of our stories as African-American cadets,” said Jamie Jenkins, a 1999 Citadel graduate who has read the novel. “We all experienced either directly or indirectly some form of racism at The Citadel. I don’t care who you are. I don’t care when you attended. We all experienced it on some level.”

A decades-long effort

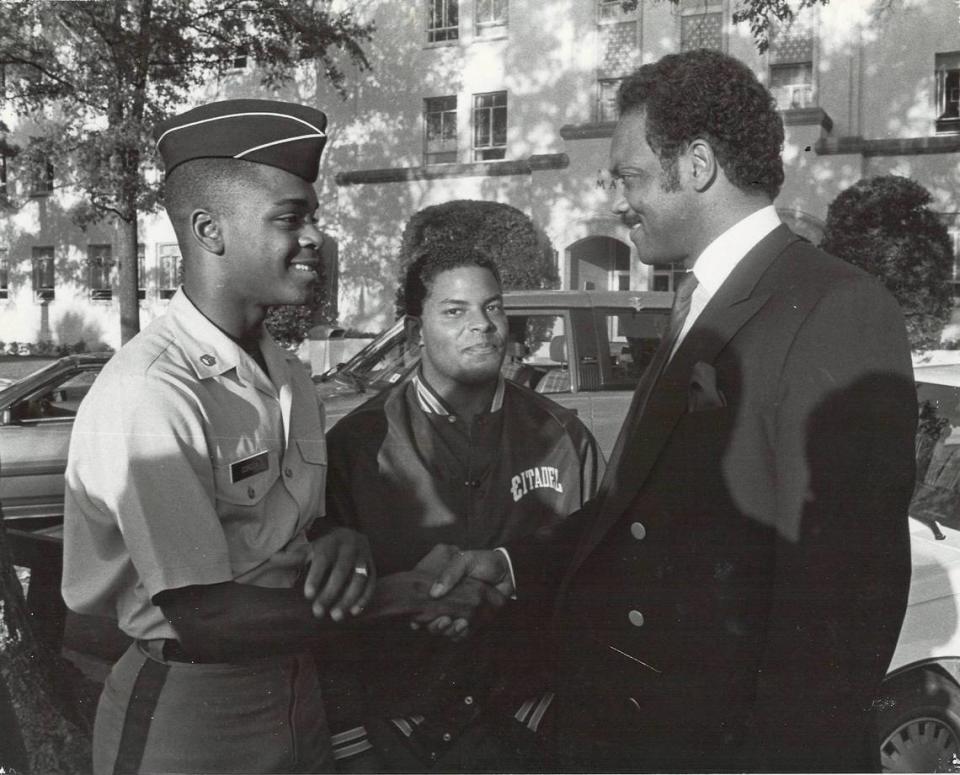

During his four years at South Carolina’s military college, Gordon became president of the school’s Afro-American Society. Under his leadership his senior year, the club began selling blue and white “Bulldog Towels” as an alternative to the Confederate battle flags that still appeared at Johnson Hagood Stadium. Sports Illustrated magazine took notice and wrote a blurb about the new symbol in the stands in 1987.

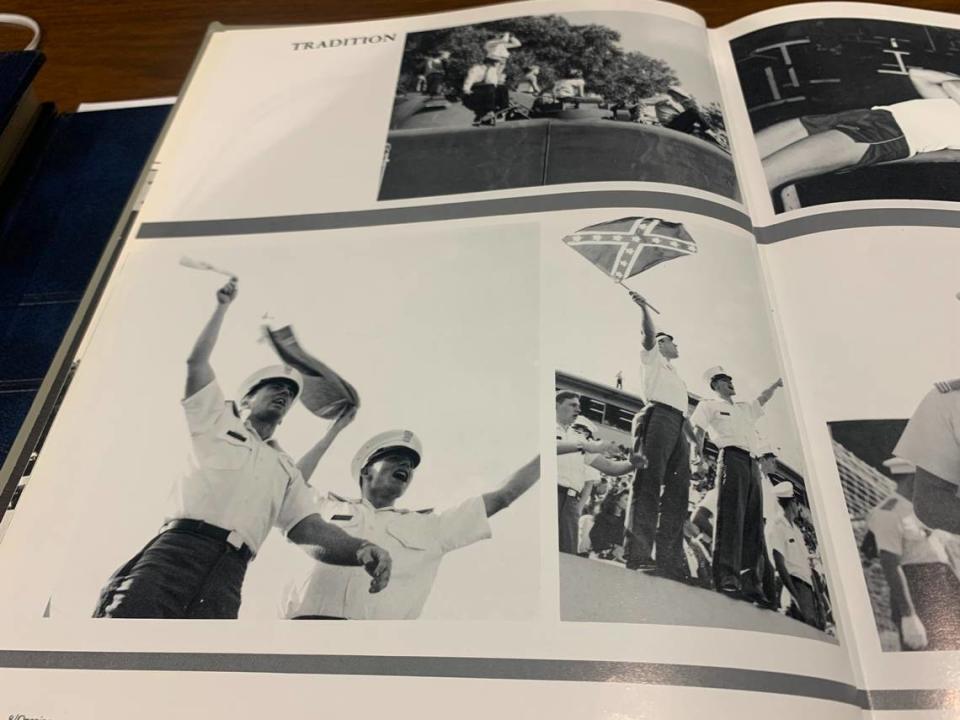

Even so, a photo spread in The Citadel’s 1988 Sphinx yearbook showed cadets waving the Confederate banner on a page titled “Tradition.” The school’s band would continue to play “Dixie” during home football games — while fans waved Confederate flags — until 1992, when a race relations committee recommended the school end both traditions.

After he graduated, Gordon refused to wear the iconic 10-karat gold Citadel ring. Each time he slipped the band of gold onto his finger, all he saw was pain.

“The experiences from The Citadel were so impactful. They were so real. And they are so painful,” Gordon said, his 54-year-old voice catching in the back of his throat. “I just don’t know if I’ll ever forget them. These are things that are written on your heart and written on the person that you are.”

In 1991, three years after graduating, he began writing a story based on his own experiences as a young Black cadet at a majority-white military college in the South. It would be written as fiction because he wanted the book to feel universal. He wanted Black graduates of any military school, whether it was The Citadel or the Virginia Military Institute, to see their stories validated within a fictionalized version of his own.

The project would take decades to complete. He was stuck on one chapter for two years.

“I would write, and I would become very emotional, so I would put it down,” Gordon said. “This was a cycle that went on for 20-something years until finally I was able to finish it.”

Through his protagonist, Jon Quest, Gordon recounts his own experiences with racism at his fictionalized “Military University of the South.” Gordon described the writing process as a form of catharsis and a chance to finally portray a group of people with similar experiences “not as victims, but as victors.”

When asked how much of the protagonist’s story is his own, Gordon zips up.

“Let me put it like this,” he said. “It is more based on truth than it is based on fiction.”

After a quick exhale, Gordon begins to talk about what happened in the early morning hours of Oct. 23, 1986. To this day, the incident remains one of the darkest chapters in the modern history of The Citadel.

In his book, it’s Chapter 9. In his life, it’s an unshakable memory.

“You know what?” Gordon said. “Truth is truth.”

The Nesmith incident

Gordon was asleep in his bunk when his room phone rattled him awake. The distinctive ring — a succession of quick, short bursts — told him the call was coming from somewhere inside the campus.

He reached for the receiver in the darkness and warned the caller, “There better be a doggone good reason you’re calling me.”

Gordon was a junior and president of the Afro-American Society. He had decided his sophomore year to get heavily involved in the group to determine ways to make things better for Black cadets.

Cadets like Kevin Nesmith.

Nesmith was 17 and scared. He was a first-year student just trying to survive his “knob” year. Under the school’s fourth-class system, freshman “knobs,” or fourth-classmen, must obey any lawful order given by any upperclassman officer.

Gordon had met the young cadet a few weeks before, but already he was worried.

“Relax,” Gordon told Nesmith at a meeting of the Afro-American Society. “You’re among friends.”

“Sir, yes sir,” Nesmith replied, his words tense and terse.

“Look,” Gordon continued, trying to put him at ease. “You can call me Kenny.”

Nesmith refused. Out of concern, Gordon pulled his vice president, Terry Adams, aside.

“Terry, I need you to keep an eye on him,” Gordon said to Adams, who lived in the same barracks as Nesmith. “The way things are shaping up this year, something bad is going to happen, and I don’t want it to happen to him.”

Now, it was Adams calling to rouse Gordon awake sometime after 2 a.m. that Thursday morning. Adams handed the phone to Nesmith’s roommate, and Gordon realized his fears for the young knob had become reality.

“Kevin is scared to death,” the voice on the other end of the line said. “He’s in his room. He’s shaking.”

Five white cadets had just stormed into Nesmith’s room wrapped in white sheets and towels resembling Ku Klux Klansmen. They chanted slurs, hissed his last name and left behind a burning paper cross before fleeing into the darkness.

School officials maintain the whole incident lasted no more than 90 seconds. It remains one of the biggest controversies at the state-supported military college of South Carolina.

At the time, it raised questions about the culture at the majority-white school and shattered perceptions of racial progress in the South some three decades after integration was declared the law of the land.

It garnered national attention. Parallels were drawn anew between The Citadel and the fictionalized version of the school depicted in Conroy’s “Lords of Discipline,” in which a group of white cadets try to drive out the first Black cadet from the made-up but Charleston-based Carolina Military Institute.

When Gordon hung up the phone that night, he looked at his teal-blue door in Padgett-Thomas Barracks. It was a facade of security in a white building that resembled a fortress.

As one of 117 Black cadets in the Corps that year, Gordon began to wonder, “Is this something that is going to start happening more to all of us?”

Gordon did not sleep that night. He kept thinking about how there were no locks on the doors.

The fourth-class system

Nesmith left the school a few weeks later.

In his resignation letter to Citadel officials, Nesmith said he was leaving “of my own free will for personal reasons.” In a Nov. 15, 1986, statement issued through his family, Nesmith shared a more complete truth: He said several cadets had continued to harass him and, under the school’s fourth-class system, he was powerless to respond.

“I feel that I have been made the villain when the villains remain at The Citadel,” Nesmith said in the statement issued through his family.

Alonzo Nesmith, a 1977 graduate of The Citadel and the first and only Black member of the school’s governing board at the time, called what happened to his younger brother an “act of terrorism” and said the white students should have been expelled.

Instead, the five guilty cadets were confined to campus for the rest of the school year and ordered to complete 195 marching tours, a disciplinary action that remains the harshest punishment issued in school history short of expulsion.

Alex Macaulay, a historian and a 1994 Citadel graduate, said the 1980s were a particularly rough period for Black cadets at the military school. However, The Citadel often reflects larger issues in society and larger changes in society.

“There were stories and anecdotes about white cadets at The Citadel at this time being very comfortable telling racist jokes, using racist slurs thinking it was funny. There are stories about racist pranks and having freshmen use racist language and make discriminatory remarks,” Macaulay said. “At The Citadel, when these kinds of abuses occur, they’re written off sometimes as being part of the fourth-class system.”

Infamous for both its rigor and its ego-crushing, the fourth-class system stated that any freshman cadet must follow any lawful order given by an upperclassman cadet.

The system would help push a widespread attitude among graduates that if a cadet left the school, it wasn’t the system that had failed. It was the cadet.

After Nesmith resigned, those attitudes surfaced in letters to the editor published in The (Charleston) News and Courier.

A 1972 graduate of The Citadel called Nesmith “a quitter” who “could not withstand the discipline and training necessary to earn the right to be a Citadel man.” The sister of a 1974 Citadel graduate wrote, “Obviously, ex-cadet Nesmith did not belong there. He couldn’t take the pressure.”

The letters also show how the school’s traditions, particularly its fourth-class system, were used to justify behavior and displace blame. To this day, what happened on Oct. 23, 1986, is known as “the Nesmith incident.”

“When people say there was no problem at The Citadel at the time, there clearly was. If you continue to deny it, though, that’s where it gets wrapped up, even now, as part of the Citadel’s fourth-class system — that this hardship is all part of the goal to make you into a Citadel man,” Macaulay said. “And if that’s the mentality, then we see how the ‘problem’ then becomes Kevin Nesmith and not his antagonists.”

But Gordon wrote a letter to the editor, too.

“I am fed up with the speculations, opinions and views coming from beyond The Citadel’s gates. If there is no problem, why do the black cadets feel that there is?” he wrote in the newspaper. “It has nothing to do with us wanting breaks. It has nothing to do with wanting life easier. I am insulted someone would assert that I am being too sensitive or using my race as a crutch. We do not seek sympathy. We strive for justice!”

Decades later, as an adult living in Alabama, Gordon said his decision to write that letter to the editor mirrors, in some way, his motivation to write “Bad Dogs: A Black Cadet in Dixie.”

“What I knew was that if someone did not speak up and provide a voice for the voiceless that it was going to get swept away, and no one would hear about it. It would end up becoming kind of a ghost story,” he said.

Col. John Dorrian, a Citadel spokesman, said what happened that night should never be forgotten. Like Nesmith, Dorrian in 1986 was a freshman at The Citadel just trying to survive his knob year. Unlike Nesmith, Dorrian is white.

“It happened right across the quadrangle from where I was also a knob,” Dorrian said.

Nesmith, he recalled, was in November company. Dorrian was in Oscar company. Though the two knobs never met, Dorrian knew Nesmith’s roommate, and Dorrian remembers him being disturbed by what had happened.

“Whenever there’s a terrible incident of this nature, it never really goes away. It affects everybody who was involved, and it affects perceptions of the institution, really, in perpetuity,” he said. “Even though you move past it, you get better, you isolate that and try to make sure it doesn’t happen again, what happens is whenever there’s an incident something like this is revisited.”

Echoes of 1986 emerged in 2015 when photos of freshman cadets wearing KKK-like white hoods surfaced on social media during the same week as the six-month anniversary of the Mother Emanuel AME church shooting.

“In that news coverage of that event, this 1986 incident was in that story,” said Dorrian, who in 2015 was not a spokesman for the college. “And so, when there’s a challenge like this —”

He paused and searched for another word.

“When there’s a problem like this,” Dorrian continued, “it revisits you.”

The Citadel’s reckoning

Founded in 1842 to respond to a planned slave uprising, The Citadel today is trying to confront its past by telling its full story.

“The best way to heal old wounds is to tell the truth about them and learn from them,” Dorrian said.

In 2017, under the direction of the University of Virginia, The Citadel joined a consortium of 40 universities studying slavery. The information will be used to provide further education in this area and to increase The Citadel’s archives to accurately tell its history.

In 2018, The Citadel was one of 10 schools in America to receive a $30,000 grant to create a Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation Center. The center has since facilitated “CitListen” sessions both on campus and in the greater Charleston community to facilitate acceptance and understanding through guided conversation.

“We’re a public school, so we belong to the people of the state of South Carolina — every single one of them,” Dorrian said.

The school spokesman concedes The Citadel still has “a long way” to go as it seeks to increase its enrollment numbers among minorities.

According to figures provided by The Citadel, the number of ethnic minority cadets increased by 25% during the decade spanning 2010-2020. During that same time, the number of female cadets increased by 81%.

In the fall of 2020, the start of the most recent academic year, the school reported having 494 minority cadets, accounting for 21.2% of its Corps.

“Some of the history probably is a barrier to them. There’s apprehension or concern,” Dorrian said. “The best way you eliminate that apprehension and concern is to be transparent about it, put it in context, and be very intentional in reaching out to people and showing them — not just telling them — but showing them what we’ve learned.”

He points to the school’s 2011 adoption of new core values — honor, duty, respect — which have become a prominent part of the college’s identity.

“Anybody reasonable who looks at the incident that occurred there (in 1986) would say we fell well short of those ideals. But having ideals and saying ‘this is what we’re about’ requires us to get better,” Dorrian said.

The Citadel is also trying to make its history public.

During the school’s 2019 homecoming weekend, Citadel archivist Tessa Updike conducted interviews with five Black members of The Citadel class of 1973 in an effort to record experiences about both Charles Foster, who broke the school’s color barrier in 1966, and the Black experience during the initial years of a desegregated Corps of Cadets.

The five men interviewed were all freshmen when Foster was a senior. Videos and transcripts of those oral histories are available on The Citadel library’s website.

“The only way you can make this place better is to tell the stories of people who’ve been here, both white and Black,” said one of the interview subjects, Norman Seabrooks, who was the first African-American football player recruited by The Citadel.

In the summer of 2020, Seabrooks gave another interview as part of the oral history project. He shared the story of the first time his mother attended a home football game at The Citadel. Shortly after the game against Boston University began, he said his mother and brother heard people screaming in the stands, “Kill the n-----s!”

When Seabrooks went home for Thanksgiving and sat down at the kitchen table, his mother began to cry,he recounted in his oral history interview.

“I am so sorry we left you in that place and you went through all the things you went through,” she said.

“What are you talking about?” he said, thinking she was referring to his freshman year.

When she refused to say, Seabrooks turned to his brother.

”She saw you at the game and she heard what they were screaming at the other players. And she heard them saying the n-word out loud and kill them. And she just —”

She had cried all the way home during the six-hour drive back to Florida. Seabrooks said his mother swore she would never go to The Citadel again.

“And for the rest of my career, including graduation, my mom never set foot on that campus again,” Seabrooks said.

Pain and triumph

After Kumba McGill graduated from The Citadel in 2005, she did not want to have anything to do with her alma mater.

When she drove past Exit 219A on Interstate-26, the sight of the green exit sign for Rutledge Avenue and The Citadel made her nauseous.

“All those emotions would come back,” said McGill, who now lives in California. “The cursing. The yelling. The name-calling. The hissing. Even now as an adult, if I hear somebody hiss, it brings me right back to being a cadet.”

Several white male cadets, she said, had hissed, “Leave my school” at her and other Black female cadets.

To this day, she said she doesn’t know whether they wanted her out because she was a woman, because she was Black or because she is both.

“Emotional scars take far longer to heal. Someone can physically hit you and it will take time, but for me it was the emotional abuse of The Citadel that left a lingering, invisible scar,” said McGill, 34.

After her four years at the school, it would take her five years to feel ready to return to campus.

“When it comes to issues of race and how you come to terms with that, I want to be clear: Our criticism is not because we hate our school; it’s because we love our school and we want it to be better,” McGill said.

For starters, she would like the school to take down the Confederate naval flag that still flies in the Summerall Chapel. McGill said it should instead go in a museum.

“To me, it doesn’t matter how many trainings you have or how many diversity committees you form if you have a symbol of hate flying in your chapel,” McGill said.

Despite multiple attempts to remove the flag — including a 9-3 vote in support of removal by The Citadel Board of Visitors six days after the 2015 shooting at Charleston’s Emanuel AME Church — the banner still hangs in the chapel.

Citadel officials say the Heritage Act prevents them from removing the flag because it is an honor display. The banner in question was gifted to the school in 1939.

The Citadel is often viewed as a stoic and unchanging Southern institution. But historian Macaulay said the school tends to “reflect larger issues in society and larger changes in society.” Sometimes, he said, change comes slowly.

“While The Citadel does change, what is bothersome and disturbing is the continuity of the experiences shared by its African American cadets. Some of the issues that were being raised in the ‘60s and ‘70s are still coming up decades later,” he said.

Gordon, the author, said he wants people — both Black and white — to start listening to each other and start asking each other about their experiences, especially alumni of military colleges like The Citadel and VMI.

“My issue, and the issue of Jon Quest in ‘Bad Dogs’ and the issue of Kevin Nesmith, was it was never the president of the college. It was the students we had to live with day in and day out that had attitudes that were negative and combative toward African Americans,” he said.

When Gordon’s father saw he wasn’t wearing his Citadel ring years after he graduated, he asked Gordon why.

“I’ll never wear that ring,” Gordon said. “With everything they put me through and how they tried to destroy me as a person and would not even regard that I was a man. I will not ever wear that ring.”

“And all those are the reasons why you have to,” his father said.

Today, Gordon said he wears the ring with pride. When he looks down at it on his finger now, he sees the pain and the triumph.

The ring, Gordon said, is “a crown of gold.”