The City Waging War on Its Strippers

BRISTOL, England—In a move that would force a hundred dancers into unemployment, a British city council is pushing a proposal for an all-out ban on strip clubs.

The proposal, introduced in Bristol in March, would force the only two strip clubs in the city to shut down—and has prompted strippers to flood the inboxes of local politicians and self-described gender equality experts who have been pushing for the ban.

One recipient for such messages is Labor Party councilor Marg Hickman, who told the Bristol Post earlier this year that “there is evidence to suggest” that some of the city’s sexist street harassment and domestic homicides are “probably” linked to its two gentlemen’s clubs—a common talking point for anti-strip club advocates.

For the most part, these emails get ignored. And so, when the Bristol Sex Workers Collective messaged prominent anti-strip club campaigner Helen Mott a few months ago, they hadn’t expected her to agree to a private zoom call.

“[Mott] said: ‘I’ve got so many of my personal feelings towards this, but I am going to put them aside,’” Chloe, who is 23 years old and has been working as a dancer in Bristol since 2017, told The Daily Beast. On the call, Chloe told Mott that her collective had spoken to police in other U.K. cities where strip clubs are banned. There hadn’t been any decrease in sexual violence since. Of course not, Mott allegedly replied.

“She kept on saying how much she respected our jobs and respected us,” says Chloe. “I ended up losing my patience and saying: ‘Why do you keep on treating us as collateral for something that’s a symbolic victory for you at best, and, like, really dangerous for us?’”

For dancers who have already been out of work since last March, this is a denigration. But the U.K.’s strip club industry was already struggling before the pandemic: In the past decade, the number of strip clubs went down from 350 to less than 150.

“The industry has been harmed by the stigma and smear campaigns,” Stacey Clare, the founder of the East London Strippers Collective, told The Daily Beast. “Every time it gets in the press that a strip club has lost its license it sends out the message: ‘Party’s over, guys, if you want to see tits get on the internet like everyone else.’”

How a Strip Club Named Tootsie’s Could Doom Miami’s Coronavirus Plan

Since the 2009 Policing and Crime Act introduced annual licenses for “sexual entertainment venues,” city councils can set conditions for strip clubs to operate under. The long list of potential rules include “no touching,” “no simulating sex acts,” and requiring “the exterior of the premises” to be “presented in a manner appropriate for the character of the area.” Several English cities have used the law to refuse to renew strip club licenses.

Beyond that, cities can even choose to ban strip clubs entirely, even if the establishments haven’t broken the rules. That’s what is at stake in Bristol, which is on the verge of becoming the biggest U.K. city to say no to the pole after a long-term campaign by those who argue that “lap-dancing clubs normalize the sexual objectification of women.” Other smaller cities have already done this: Most recently, the seaside town and bachelor night destination Blackpool banned strip clubs entirely to improve its image as a “family holiday resort.”

When Stacey Clare started dancing as an art student in Scotland in 2016, she told The Daily Beast she was “aware of this media hoo-ha around lapdancers.”

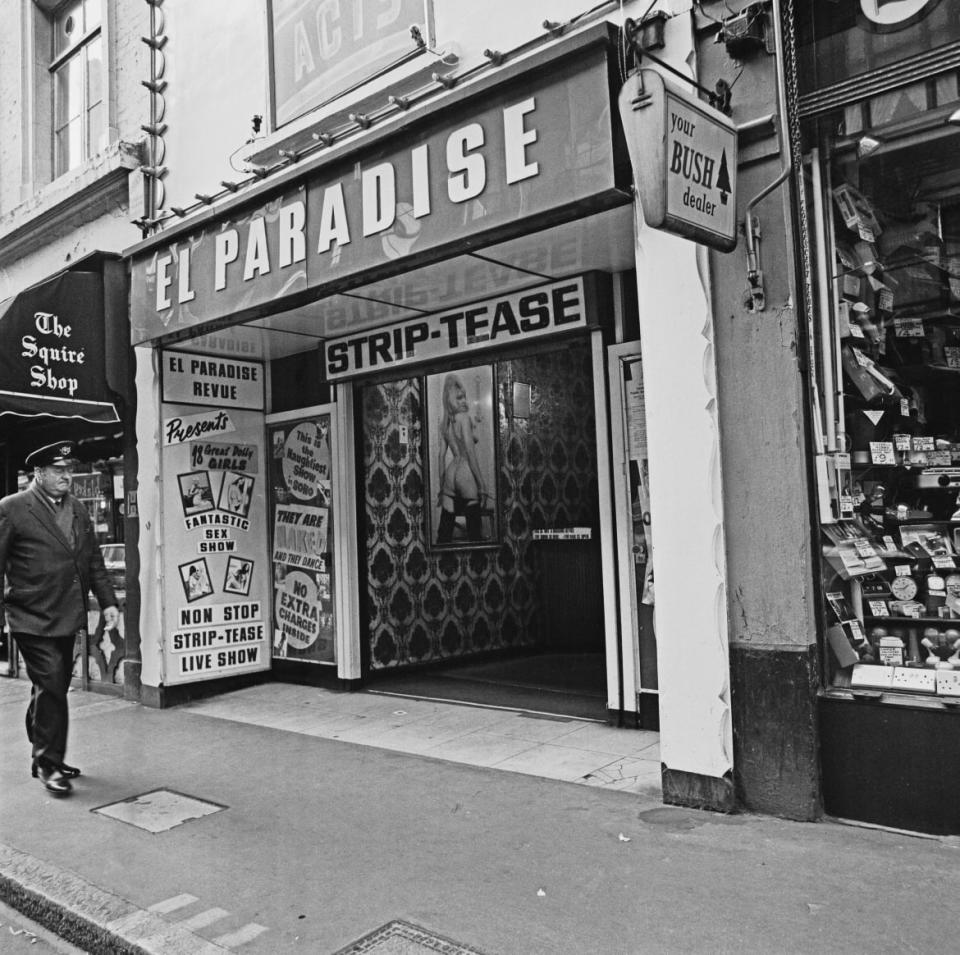

El Paradise, an erotic live show on Brewer Street in Soho, London, in 1974.

Around this time, strip clubs in the U.K. were not strictly regulated.

“Back in the ’80s, ’90s, a pub could hire a stripper for the night, you’d do a whip-round where everyone puts money in a pot,” says Clare. “I think as more women entered these very privileged workspaces, they didn’t want to take part in this kind of corporate entertainment.”

In 2002, a domestic violence charity called Eaves Housing for Women published a research report about lap-dancing clubs called the “Lilith Report,” which, amongst other things, falsely claimed that opening strip clubs in Camden led to a 50 percent increase of rapes in the area.

The report was eventually debunked in 2011, but by that point, the damage was already done: “The press got hold of that claim and it just became fact,” said Clare.

One of the feminist campaigners on the social impact of strip clubs on women and children nearby was Sasha Rakoff. According to the One World’s Action’s 2010 “100 Women of the World” list, Rakoff—a trained scientist and website designer—had a feminist reckoning when she saw a small girl in a hospital pick up a copy of the Sun tabloid and ask her parents why there was a naked woman in the newspaper.

In 2003, Rakoff founded the British anti-strip club pressure group Object, which campaigned with the feminist Fawcett Society to get strip clubs shut down. They were advised by a lawyer called Philip Kolvin, who claimed to be alarmed by his colleagues shamelessly visiting strip clubs after work. Their compromise with the councils, business owners, and police resulted in the 2009 Policing and Crime Act.

Since then, Kolvin has had a change of heart, and now defends strip clubs at risk of losing their license. Clare says Kolvin has since “been on a journey,” and has been in contact with her collective. “He sort of shakes his head and says: ‘We did such a bad job with the Policing and Crime Act, we didn’t consider the dancers.’”

Back in 2009, not many strippers wanted to speak out in public, and the law made working conditions even worse. Clare founded the East London Strippers Collective in 2014, four years after Rakoff launched an anti-strip club pressure group called Not Buying It, aimed at “exposing” strip clubs for breaking rules and legally challenging the decisions of U.K. councils to license strip clubs, on grounds that they have a negative impact on women.

Rakoff and Clare met by chance in 2015, when London’s Camden Council was looking for opinions on what to do about a local strip club that wasn’t following the rules. “I knew from looking and talking to her that she wasn’t a dancer,” Clare said. “As soon as she knew I was a dancer, she just shut down, she didn’t want a conversation. I think she’s built a career off these claims, she’s published papers and done paid talks, she’s really invested in the narratives.”

In Bristol, the city council is soon set to conduct a 12-week survey to see if people actually want the strip club ban imposed, the results of which will determine the fate of the two establishments.

Inside ‘Demon Time’: The Out-of-Work Women Stripping on Instagram for Celebs During the Pandemic

One major proponent of the ban is the women’s rights organization Bristol Women’s Voice. Recently, the group conducted a survey on street harassment. For the group’s director, Katy Taylor, a strip club ban would be “a small step towards helping reduce environments that perpetuate men’s problematic attitudes,” she told The Daily Beast. If the policy is rejected, she says, campaigners could bring a legal challenge against the council, Not Buying It-style.

Taking away a strip club’s license doesn’t cost the council much. In a city where some waitlists for sexual assault counseling services are currently around 18 months long, “It’s not often that you have a chance to make a difference,” Taylor said.

Taylor explained that she has spoken to dancers in Bristol, but wonders, “Do they acknowledge the broader argument?” which she claims is that strip clubs cause “community harm.” (The Bristol Sex Workers Collective still hasn’t received the “evidence” that Hickman refers to, despite sending several Freedom of Information requests.)

Two years ago, a separate survey showed that two thirds of Bristoleans don’t care about the clubs either way. So some dancers, like Chloe, are optimistic. But even without the ban, Chloe said, “I’ve experienced how scared we all are every year, when these people come out of the woodwork and try to get our licensing renewal shut.”

Front Bed Show Brewer Street, Soho, circa 1987.

And then there’s also the panic triggered after Not Buying It—in a bid to gain “hard evidence” that the dancers in a Spearmint Rhino strip club in Sheffield were breaching the conditions attached to their license—hired ex-police officers to pose as customers and film strippers with cameras hidden in their glasses in February 2019.

It wasn’t the first time a man of the law snuck a camera into a lap-dancing club. Back in the ’80s, London strip club owner Peter Stringfellow hired private detectives to look into the newly opened chain strip club Spearmint Rhino, which was luring away his customers (initially, he sent some of his dancers to work there undercover, but the money at Spearmint Rhinos was so good that they never came back.)

“That Sasha Rakoff has gone and replicated the same behavior of the male strip club bosses that she hates so much, that she wants to run them out of business—that’s the bit that just blows my fucking mind,” says Stacey Clare. “You don’t have dig deep to find stories of police brutality against sex workers. For her to overlook that... it shows how little empathy she has for us.”

At the club where Chloe works, many dancers have day jobs, working as nurses or in banks. They aren’t “out” as strippers. Not Buying It’s hidden camera has freaked out dozens of women on the job.

“We all got terrified of speaking to anyone with glasses,” says Chloe. “Not that we were doing anything wrong. But I don’t think the actual girls were either.”

One of the dancers who was filmed in Sheffield told Chloe that she had, at some point, asked the undercover cop to take his glasses off. “He said: ‘Oh can I put them back on? Because I can’t see very well,’” Chloe said. “She must be kicking herself, poor thing.”

After the secret filming, the dancers tried to bring legal action against Not Buying It for violating their privacy rights. They decided to work with Spearmint Rhino’s management in bringing the case about. Ultimately, the club’s lawyer failed to get the dancers anonymity before the trial, and they had their real names released in court.

The club dropped the case last summer, reportedly because they couldn’t afford to fight the case because of the coronavirus restrictions.

“I’m still really upset that there wasn’t any legal recourse for the filming,” Chloe says. “It really grosses me out.”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.