In city where assassinated Haiti president is to be buried, politics of color take root

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

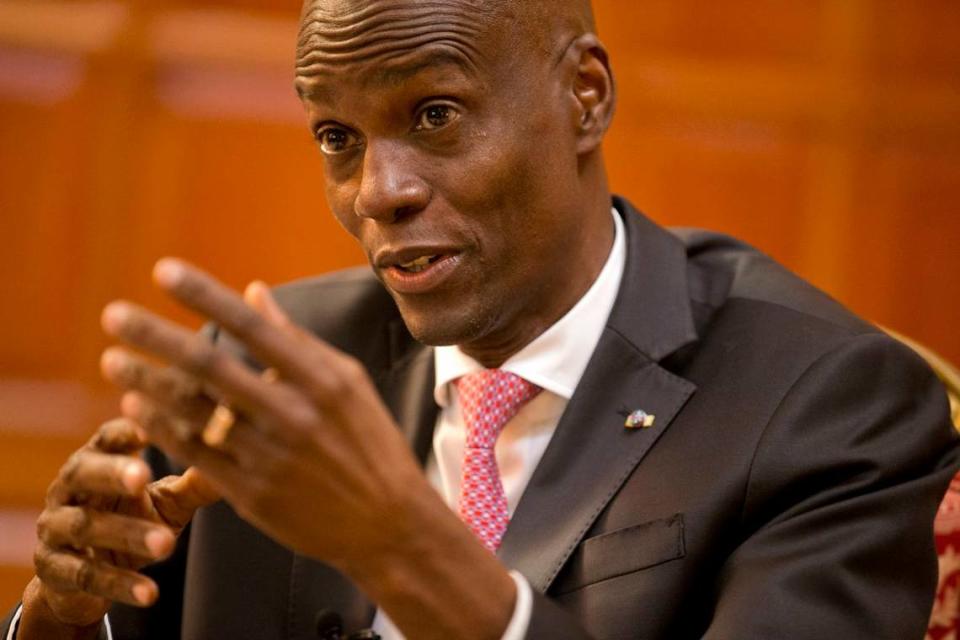

Born in the small town of Trou-du-Nord in the northeast, coming of age in the northern port city of Cap-Haïtien, and carving out a living in Port-de-Paix in the northwest, Jovenel Moïse, the man who became Haiti’s president, was a self-proclaimed moun andeyò.

That is the label Haitians from this city use for people from the back country. Moun la ville is used for those from Port-au-Prince, the capital.

That distinction is now stoking tensions in this colorful historic city of French-inspired gingerbread houses, narrow streets and large rural plantations — not just over centuries-old exclusion and inequalities, but over race and shades of skin color in the world’s first Black Republic founded by former slaves.

It’s a recurring theme throughout Haitian history, where political conflicts have long been rooted not just in regionalism, but in the politics of what historians call colorism: Noirism, emphasizing blackness, vs Mulattoism, emphasizing mixed-race heritage.

On Thursday, as Haiti prepared to bid farewell to Moïse more than two weeks after he was assassinated in a brazen middle-of-the-night attack inside his private residence in the country’s capital, tensions in Cap-Haïtien ran high as supporters and non-supporters alike equated his death as a plot by the country’s Port-au-Prince-based elite against the poor black majority

Roads into the city from the capital were blocked, and fiery barricades were erected. A bridge was burned and shots were fired as protesters fanned out across the city, demanding justice for the dead president. Protesters shot at a restaurant as journalists tried to take video, attacked a foreign videographer in front of a hotel along the oceanfront and threw rocks at a diplomatic car, forcing security guards to fire their weapons and flee with a foreign diplomat.

For some here, Moïse was killed by the “red people” of Port-au-Prince, the lighter-skinned Haitians whom he labeled as “oligarchs.” In speech after speech, the embattled leader, dogged by corruption allegations from the moment he took office in 2017, blamed the “oligarchs” while trying to explain his failure to meet his campaign promise to bring “the land, the rivers, the people and the sun together to have a rich country.”

“There wasn’t any improvement under him because they were oppressing him,” said Francois Augustin, 64, a local resident, accusing the nation’s Parliament and the economic elite for the president’s failed promises.

Emile Eyma Jr., a local historian and president of the Capoise Society of History and Heritage, said the introduction of race in the discourse over Moïse’s death is worrying, but it’s an issue that Haiti must address because “it masks the real problems of the country.”

“As long as we don’t address it, colorism and regionalism will always be used politically,” he said. “They are not the fundamental problems of the country; it’s production, because we don’t produce; we have become dependent on import, and the riches of the country are unequal. The problems of justice, the problem of corruption, these are the real problems.”

The tensions and the use of color as a marker of oppression are opening a dangerous Pandora’s box, some Haiti experts fear.

Before he became president, Moïse was head of a local chamber of commerce, which made him part of Haiti’s “Black” elite. Still, throughout his presidency, it was his humble beginnings as “the son of a peasant” that he used in speeches as he railed against “a small group of people” he said were holding Haiti hostage and responsible for its economic, political and social turmoil.

Robert Fatton, a Haiti-born political scientist and the author of several books on Haiti, says the portrayal of Moïse as an outsider coming to Port-au-Prince and taking power, only to be assassinated by the “red people,” is a theme in Haitian politics that goes back to the assassination of the country’s first leader, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the former slave who declared Haiti free from French rule on Jan. 1, 1804.

“In recent times, politicians in search of power have manipulated” the color issue time and again, Fatton said, which has helped mask “the reality that both ‘the light-skinned mulatto’ and the ‘black elite’ have behaved with similar contempt for the poor black majority.”

“It is true that color has always been a marker of relative privilege since the colonial times of slavery, as the affrancis, the “free” people of color, were mostly mulattoes,” Fatton said. “This contributed to the roots of ‘colorism’ in the political conflicts that have marked Haitian history before and after the founding of the republic in 1804.”

Fatton said he fears where the divisive issue of color will lead.

With Haiti in the midst of an electoral cycle to choose a new president, members of parliament and local officials, Moïse’s partisans are seeking to recast him as a national hero, rather than an unpopular president, as part of an electoral strategy to win elections by claiming closeness to him.

During a Catholic Mass in his memory on Thursday at Our Lady of the Assumption Cathedral, the half-empty church was filled with people wearing T-shirts with Moïse’s image.

“Thank you, President Jovenel Moïse because you gave your life for the people’s fight, and it will continue,” some of the shirts read in Creole.

Others invoked the name of a key hero of the Haitian revolution and Haiti’s self-proclaimed Emperor, Henry Christophe.

“Henry Christophe welcomes you President Jovenel Moïse,” such shirts also read.

As Haitians paid homage to Moïse inside the cathedral, some shouted, “Justice before funeral,” while others said he “was not a dog. He cannot be buried before he gets justice.”

Jefferson Etienne, 28, said the death of a president is not something he would have ever envisioned in his life, and compared it to “a stab in the heart.”

While he doesn’t know who killed the president, he railed against “the mercenaries who are holding this country hostage.”

The mercenaries, he said, are the economic elites who had become a target of Moïse’s speeches.

“They have dropped the country in a black hole,” said Etienne, sitting inside the church, his body covered with splatters of paint from spending the last three days painting street poles in the president’s honor. “Every time we find a president speaking for us ... either he is forced into exile or he is assassinated.”

In the 18th Century, this city, then known as Cap-Français or Cap-Henri, was one of the richest ports of the French empire and even bore the nickname the “Paris of the Antilles,” because of its wealth and French-influenced architecture. It was here that the last significant battle of the Haitian Revolution was fought, after black and mixed-raced slaves in 1802 decided to join forces to defeat Napoleon Bonaparte’s army.

It is not lost on some that Cap-Haïtien was also once the capital of the State of Haiti, when Christophe, a hero of the independence, ruled over the north and Alexandre Pétion, who was lighter-skinned, ruled over the south, present-day Port-au-Prince.

While the geographic division went away when President Jean Pierre Boyer united the country in 1818 following Christophe’s suicide, the divisions still linger socially and politically in the Haitian psyche.

“I’ve never liked visiting Port-au-Prince,” said Ronald Fils-Aimé, 43, standing in a public plaza where French colonizers once displayed the heads of slaves on poles to deter revolt. “They always make people from Cap-Haïtien feel like they are less intelligent.”

People from the capital, he said, make fun of the way people from the north speak Haitian-Kreyòl, and their preference for the language over French.

“We don’t speak the same way as them,” he said.

Like others here, Fils-Aimé turned to history to put Moïse’s death into context.

“Once a president comes from the north, they kill him,” he said.

Before Moïse’s death, there were four presidents in Haitian history assassinated in office: Jean-Jacques Dessalines on Oct. 17, 1806; Sylvain Salnave on Dec. 19, 1869; Cincinnatus Leconte on Aug. 8, 1912; and Vilbrun Guillaume Sam on July 27, 1915.

Sam’s killing — he was dragged outside of the French Embassy and murdered — led to the 19-year U.S. occupation of Haiti.

While Haitians may not be able to name all of the assassinated presidents, there is one name they constantly bring up: Dessalines.

In recent days, Moïse’s supporters in Port-au-Prince have eulogized him as the reincarnation of Dessalines, who was slain outside of Port-au-Prince in a plot by, among others, Alexandre Pétion.

During Thursday’s Mass, Monsignor Launay Saturné, president of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Haiti and archbishop of Cap-Haïtien, steered clear of the race and color tensions.

But he talked about the other tensions the Catholic Church has tried to deal with in the past few years: the violence ripping through lives in Haiti’s poor communities.

No one is immune, he said, as he spoke of the president becoming the latest “victim of a harsh crime.”

The priority in Haiti, he said, should be political stability and an end to the killings.

“We need to breathe,” he said. “ To get back to a normal life.”