The Civics Project; What is gerrymandering?

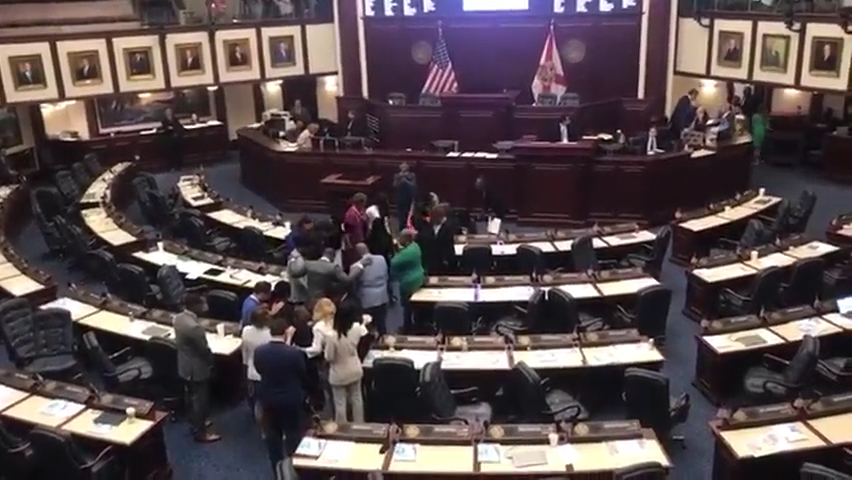

With a Florida court striking down Gov. Ron DeSantis' proposed district lines this week, the issue of gerrymandering again came into the public eye. This column first ran in 2020.

Q. I’ve seen a lot of talk about problems with gerrymandering but I’m not clear what it is and what the big deal is.

A. Gerrymandering is when lawmakers draw legislative districts to favor one group over another. It’s the practice of legislators picking their voters rather than voters picking their representatives. The discussion today is primarily over partisan gerrymandering, which is constructing districts to advantage one party over another. Our country has a disturbing history of racial gerrymandering as well, which has been used to dilute minority voting strength. Racial gerrymandering is illegal and unconstitutional, though not entirely absent.

Partisan gerrymandering is very much alive and well and is practiced by both major parties. The idea is that while districts have to be contiguous and roughly equal in population, the population can be very different depending on where you draw the lines. Since districts don’t have to be any particular shape, the trick is to draw as many districts as you can with a majority of your voters.

The name gerrymandering comes from the 19th Century. In 1812, Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry approved a law that created odd-looking legislative districts. One appeared to be roughly in the shape of a salamander, leading critics to create the nickname gerrymandering.

Since the days of Gov. Gerry, legislators, with the help of big data, have gotten sophisticated at manipulating district line-drawing, down to the precinct level. The strategy is not that complicated. It comes down to what's known as packing or cracking. Packing is when you stuff as many opposition party voters into one district as you can. While this creates an opposition district, it allows you make several surrounding districts where your party can comfortably win. Cracking is dividing up the opposition voters into small groups in several districts, so that they can’t get a majority in any district.

If done well, you can have a state with a 50/50 split of Republican and Democratic voters but a supermajority of representatives from one party. Historically, some districts are notorious for their odd design. Ohio's "snake by the lake" 9th District runs from Toledo to Cleveland and is so thin in parts that some people fear erosion might split it. One Maryland district was described by one federal judge as a "broken-winged pterodactyl lying prostrate across the state."

Aside from the important questions about fair elections, gerrymandering can have a corrosive effect on governance. When representatives are elected from safe partisan districts, it makes it difficult for them to reach compromises with the opposition. Without compromises and cooperation, our government has a tough time operating.

Solving partisan gerrymandering is difficult. The party in power is often reluctant to give up this advantage. The U.S. Supreme Court has largely allowed states to do it, and state courts have been inconsistent, with some prohibiting it. Some states, like Arizona, have tried to reduce it by taking districting away from legislators and giving it to an independent commission.

Florida passed requirements that legislators not draw districts to favor a party. However, those rules require courts to enforce them.

Kevin Wagner is a noted constitutional scholar, and political science professor at Florida Atlantic University. The answers provided do not necessarily represent the views of the university.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Gerrymandering is redrawing district lines to tilt an election.