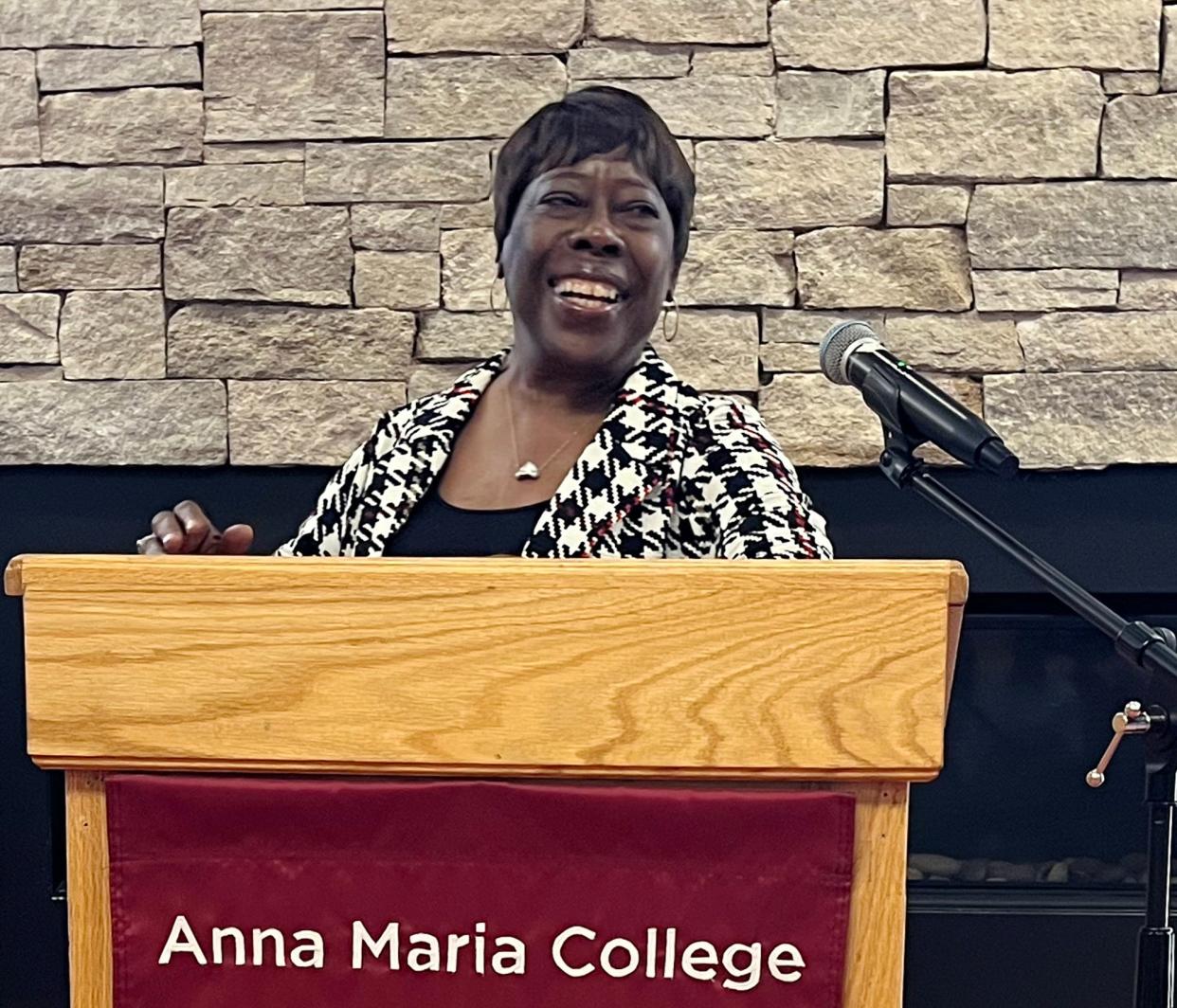

Civil rights activist Bettie Mae Fikes, 'the voice of Selma,' recalls turbulent '60s with a song in her heart at Anna Maria College

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

PAXTON — Bettie Mae Fikes, a founding member of the Freedom Singers during the U.S. civil rights movement, held court for over an hour at Anna Maria College's Foundress Hall for over an hour Monday afternoon as she shared recollections from the '60s interspersed with the gospel hymns she has worked to historically document.

Fikes, 76, known as the "the voice of Selma," became a student leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, traveling with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with the Freedom Singers, to which she remains a member.

Originally from the Selma area, Fikes came from a family of church gospel singers and began singing with her mother at the age of 4. She has performed with musicians such as Joe Turner, Albert King, Bob Dylan, James Brown and Mavis Staples. In 2020, Fikes performed at the funeral service for Georgia Congressman and civil rights icon John Lewis.

Fikes has also delivered speeches at universities across the U.S. and Canada for about 20 years.

"We were young. I didn't know freedom would cost so much. Seeing loved ones die. Stories haven't been told. Not all of true stories. If you all knew what we went through."

Bettie Mae Fikes, a founding member of the Freedom Singers during the U.S. civil rights movement

During the civil rights movement, Fikes and other Freedom Singers would often change the lyrics of popular gospel songs to reflect the goals of the movement and lead marches. She was also jailed for several weeks in 1963 for protesting.

Woke every morning prepared to die

At Anna Maria College, Fikes described sit-in protests of segregated restaurants and the first of the freedom rides, where other activists rode buses into segregated states to challenge the continued segregation of buses in the south. Fikes said the young activists woke up every morning prepared to possibly die for their protest and they were met with open hostility and violence.

"I don't want you to picture (the start of the freedom rides) as something bad. I want you to picture this as growth. Because that day started an awakening," Fikes said.

Fikes repeatedly said the history of the civil rights movement would later be heavily documented and re-told, but often inaccurately.

"We were young. I didn't know freedom would cost so much," Fikes said. "Seeing loved ones die. Stories haven't been told. Not all of true stories. If you all knew what we went through."

Music and the performance of music helped to keep the activists going as they faced a brutal response, Fikes said. She said the connection to music that the activists had and connection to the gospel tradition has faded in the decades after the civil rights movement as the traditional moans and laments of the Black church have begun to decline.

Fikes has worked with the Smithsonian Institute to document those moans whereever they can still be found in churches.

"You don't find the moans in churches today because it's a new era," Fikes said. "We're losing the most significant and important parts of our life and culture."

A song in their hearts

Fikes said young people need to have a song in their hearts and approach the world with love as they face future hardships and push for change.

"If you don't have a song in your heart and if you have not been in a position to help someone, the time's come," Fikes said.

Fikes repeatedly joked and nudged at the audience to join her in song during the presentation, getting a few to join with claps near the end of her lecture and some shy singers to accompany the ending rendition of "This Little Light of Mine."

During a question and answer segment, Fikes said the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a momentous occasion for members of the movement.

"I thought we had accomplished something that was so great it was going to impact the whole world. And I must say it did impact the whole world," Fikes said.

When a young boy asked Fikes why she sang during her presentation, she said singing is a form of freedom of the spirit for her.

"Some people sing, some people talk, some people write poetry. Singing is my thing," Fikes said. "And it's not a talent It's a gift."

Bringing people back to civil rights movement

In an interview with the Telegram & Gazette, Fikes said she tries to bring younger people who attend her events back to the civil rights movement, saying it can feel strange to see attendees watch silently as they hear the stories she tells.

"I hope they're absorbing it well enough to put it (in their hearts) and to carry it on," Fikes said. "Times are so much different now than it was back then. What we had then is nothing compared to what you have today ... you have more to do than we had then. We were just setting up the foundation for you."

Fikes said she hopes attendees remember to go forward with love.

"The thing I always like to say is, 'Don't listen exactly to what I say, but listen to what I say to do,'" Fikes said. "And what I say to do is to keep love in your heart and keep moving. Today we're not loving like the older people did back then."

This article originally appeared on Telegram & Gazette: A song in your heart: Fikes of Freedom Singers speaks at Anna Maria