He claimed he was visited by aliens and could clone babies. Why do thousands believe him?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

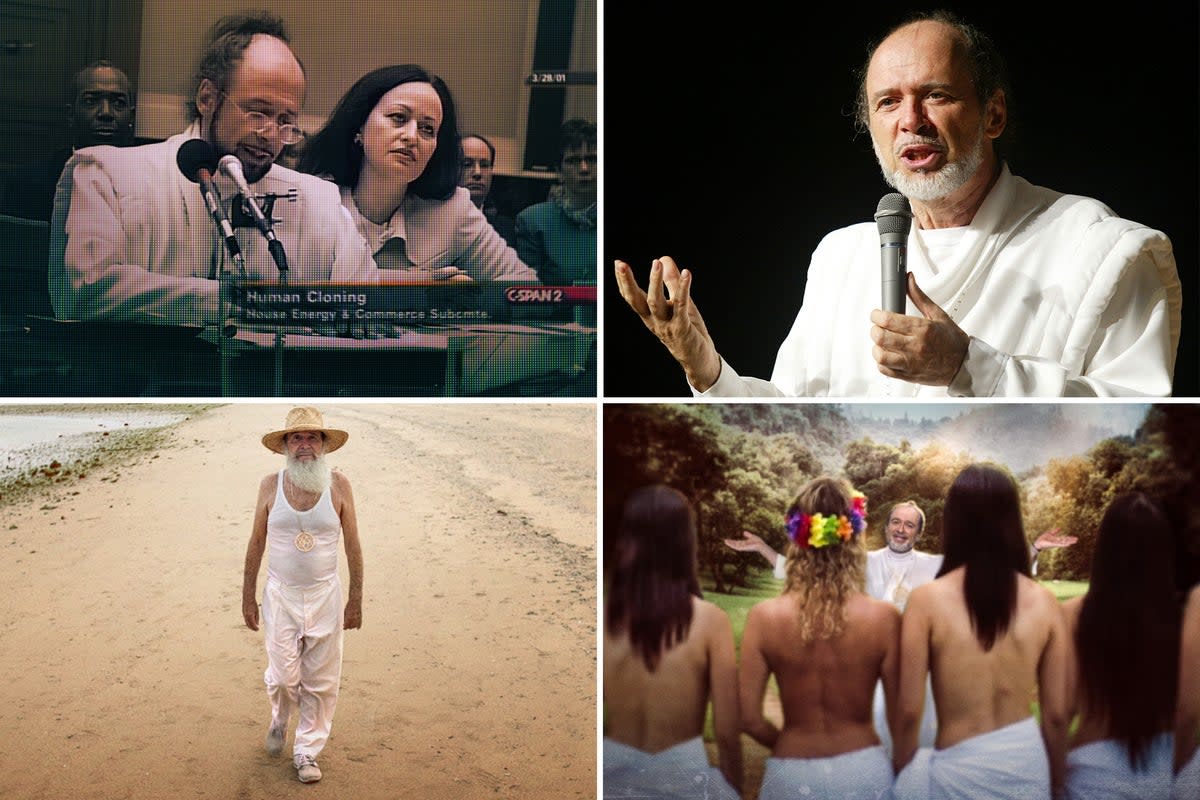

Claude Vorilhon, a man known to thousands as Raël, has a story. It goes like this: One morning in December 1973, Vaurilhon went for a walk on a volcanic stretch of highland in his native France. There, Vorilhon claims he was visited by an alien who revealed to him that his people, the Elohim, had created human life on earth. Two years later, in 1975, Vorilhon claims he was visited by aliens again, and this time taken to visit their planet.

From those encounters, Vorilhon says he came back with a mission: spread the word of the Elohim on earth, and prepare its inhabitants for the aliens’ upcoming return. Using that set of beliefs, Vorilhon started Raëlism, a movement that has endured for five decades and spread across continents—and which the French parliament, back in 1995, classified as a cult.

Vorilhon and his Raëliens—as his followers are known—are infamous in France, where they regularly make headlines. (I told a French friend I was working on this story and asked: “You’ve heard of Raël, right?”—“I’m a millennial,” she shot back without a second’s hesitation. “Of course I’ve heard of Raël.”)

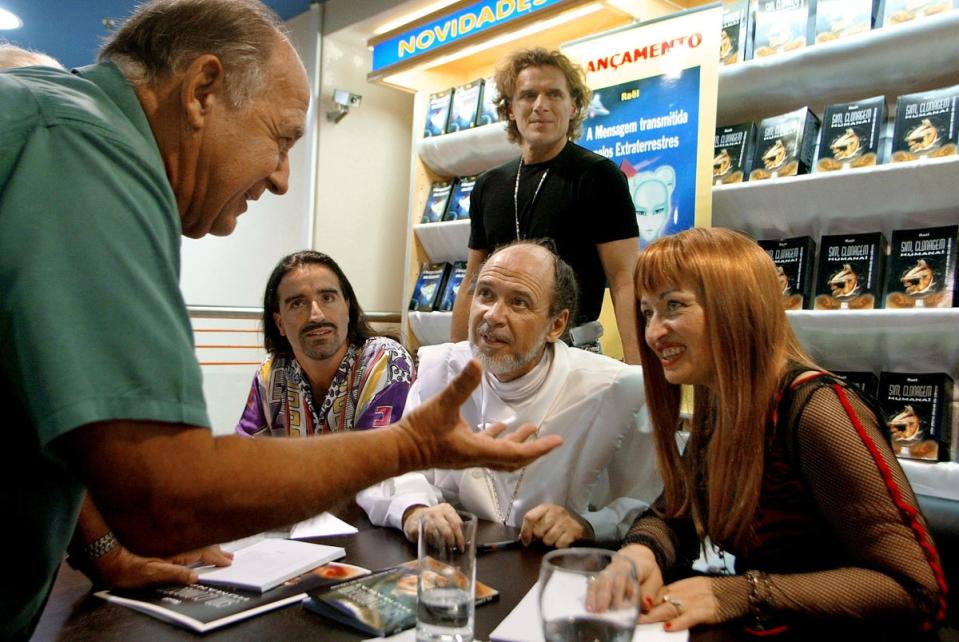

A new Netflix documentary is bound to introduce the movement to a brand-new audience around the world. Raël: The Alien Prophet, a four-part docu-series featuring interviews with current and former members, as well as Vorilhon himself, is a sweeping, in-depth, richly documented dive into Raëlism. It’s also a compelling examination of why and how people join and remain in such groups, no matter how sensational their gospel.

Vorilhon was born in 1946 and raised in the small town of Ambert in central France. In a 1994 French TV interview conducted by the notoriously crotchety host Thierry Ardisson, Vorilhon described his father as “unknown” and his mother as a “very sweet” homemaker. He was a fan of the Belgian singer Jacques Brel and moved to Paris to try his hand at a singing career—which was “quickly forgotten”, as noted in a 2003 write-up by the French newspaper Le Parisien. Vorilhon told Ardisson he did “everything he had to do” to avoid doing his military service), then became a journalist—or, as he put it himself, he was an auto racing enthusiast, and he “tried, via journalism, to have [access to] race cars.”

This all changed in the 1970s, when Vorilhon reinvented himself as Raël (the name he claims was given to him by the aliens) and styled himself up as a prophet. Within two decades, his movement had caught the attention of French authorities. In 1995, the French National Assembly investigated cults it deemed “dangerous”. Among organizations cited in its findings was the Raëlian movement, for its “antisocial” rhetoric, its alleged tendency to disturb the peace, and for its “exorbitant” expectations of financial support.

At that time, the French National Assembly estimated that the Raëlian movement counted around 20,000 members worldwide, including 1,000 in France. In 2002, an article by Le Monde estimated that the movement had just 5,000 members around the world. (The movement itself claimed to have ten times that amount.) Vorilhon himself has left France; he once lived in Quebec and has since settled in Japan.

Étienne Jacob, a journalist at the French newspaper Le Figaro, attended a weeklong Raëlian seminar in 2022 while undercover, posing as a newcomer interested in joining the movement. He felt “pampered”—but only as long as he remained “in line.”

“I had to ask questions,” he tells The Independent. “And as soon as I asked questions that bothered people, I felt that it wasn’t the done thing. Being too curious wasn’t a good thing. You had to put your blinders on, and that was it.”

Vorilhon wasn’t present at the seminar, but he did appear via video. An “incredible” clip of him aired, specifically, prior to a collection, according to Jacob. In the video, Vorilhon claims he doesn’t usually accept financial donations, but that he’s making an exception and giving people the opportunity to contribute, Jacob says.

“It seems very simple,” Jacob tells The Independent, “but in the moment, people go, ‘Well, I’m going to take out my wallet.’”

To this day, Vorilhon insists he doesn’t get a salary from the Raëlian movement—but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t make a living off his status as a self-styled prophet. “To ensure that money from the Movement is NOT used to pay a salary to Rael, there is a separate entity named, ‘Raelian Foundation,’ [sic] which supports Rael financially,” the movement’s website states.

As explained by Vorilhon in his 1994 TV interview, members can “buy magazine subscriptions” or contribute 3% or 7% of their income to the movement, depending on the rank they wished to attain (the higher the rank, the more significant the contribution). That system was reflected in the 1995 findings by the National Assembly, which mentioned an additional 10% tier. The money, Vorilhon claims, serves a purpose: it’s meant to go toward the building of an “embassy” to welcome the Elohim once they decide to return to earth.

During his seven-day seminar, Jacob says he witnessed Vorilhon delivering, via video link, a “disturbingly populist” address, “in which he brought up every crisis in the news.”

“The forests burning? [According to him], that wasn’t true,” Jacob says. At the time, an outbreak of the mpox virus was making headlines, but “for him, that didn’t exist,” Jacob adds. The message, he says, amounted to “if you stop thinking, things will get better”.

The Raëlian movement revolves partly around the idea of sexual liberation—or rather, its specific concept of it. Click around the organization’s website, and it won’t be long until you find a free PDF of Sensual Meditation, a book authored by Vorilhon in which he claims to teach people how to attain “the cosmic orgasm” via the titular practice of “sensual meditation”—a combination of meditation, massage, kissing, and stroking.

Netflix’s Raël: The Alien Prophet touches on the blurring of boundaries in an organization that revolves so intensely around one man and his gospel—and questions whether consent is even possible in the context of such hierarchy.

During his undercover stint, Jacob found the Raëlians he met “very tactile” and, at times, disarmingly forthcoming. A man who, according to Jacob, walked around naked in their shared bungalow asked him on the first day about “taking photos together”—which Jacob first took to mean group shots, but which he later realized meant photos of himself. A woman “twice [his] age” came on to him “very quickly” and “very intensely” because she felt a “very special connection” between them.

The organization has faced claims that it allows, encourages, or turns a blind eye to the sexualization of young people, which Vorilhon has vehemently denied. Raël: The Alien Prophet includes footage of a 1992 interview in which French TV anchor Christophe Dechavanne confronts Vorilhon on the topic—as well as a contemporary interview of Dechavanne himself. In 1999, the National Assembly, in a new set of findings, wrote that “Raëliens advocate for sexual initiation from the youngest age”. In 2006, Le Parisien reported that two former members of the movement were found guilty of “systematically corrupting teenage girls”. The Independent has contacted the Raëlian movement for comment but did not receive a response before deadline.

The book Intelligent Design: Message from the Designers, authored by Vorilhon and available to peruse on the movement’s website, includes this passage: “At the root of all violence, there are always sensually dissatisfied people. This is why we must learn to enjoy all of our senses, and help everyone around us to discover their total sensuality, starting with children. It is not sufficient to show them ‘how it works’, like sexual education tends to do, but we must teach them ‘how to use it’ so as to obtain and give more pleasure. Sexual education should be replaced by sensual education.”

The Raëlian movement made international headlines in the early 2000s when it made flamboyant—and evidently unfounded—claims that it had mastered human cloning and produced a “baby clone”. Raël: The Alien Prophet explores this especially outlandish claim in the movement’s history at length, and suggests that to adepts, it might not fundamentally matter whether it was true or not.

Phillips Stevens Jr, a retired associate professor of anthropology at University at Buffalo College of Arts and Sciences who has long studied religion, spiritualism, and cults, suggests that people might stay in movements such as Raëlism more for social reasons than for the doctrine itself. He refers to the 1981 book Strange Gods: The Great American Cult Scare by researchers David G Bromley and Anton D Shupe, who looked into several communities that were causing concern at the time.

“They interviewed members who across the spectrum regarded it as a very meaningful experience—and many of them joined for purely social reasons,” Stevens tells The Independent. “And the ideology that was expounded by the leader was just not a factor in their membership.”

Stevens came to the same conclusion himself after doing some personal investigation into New Age groups in Buffalo, New York.

“[People] met periodically to listen to some really off-the-wall speakers about a huge variety of impossible things,” he says. “And it seemed to me that they listened politely, gave applause, and so on—but these events were always a part of a larger get-together. People were kind of passive about the speaker, but really excited to see each other. There was a lot of hugging. I came to the conclusion that the social dimension of these groups may be stronger.”

Jacob had a similar impression during his week-long immersion with the Raëlians. “Lonely people can get a feeling of belonging,” he tells The Independent. “It gives them a goal, too, to be told that they need to contribute so that an embassy can be built for the aliens. It gives them hope, when they live in such an anxiety-inducing world.”

The longer someone remains inside the movement, the more entrenched it becomes in their daily lives, Jacob points out. Raël: The Alien Prophet’s exploration of that idea—and of the seeming impossibility of leaving—leads to a poignant moment in episode four, in which a now-former Raëlian reflects on his years spent inside the organization.

“It’s always the same thing, with these movements,” Jacob says. “They close you off, so the more time you spend inside, the harder it is to leave. When your social circle is mainly made up of other members, if you leave, you’re left with nothing. Just a void.”

This is an interesting moment for Raël: The Alien Prophet to come out. Not only did the group recently celebrate its 50th anniversary, but the deadline by which Vorilhon claims the aliens will return is approaching. He has always insisted the Elohim would visit again by 2035. Back in the 1990s, that might have seemed far-off, but now it’s just 11 years away. Vorilhon, who was born in 1946, will likely still be alive by then, and in his late eighties. What is to become of the Raëlian movement when the prophesied alien return fails to materialize?

It will probably find a way to carry on. Even outside of cults, doctrine has been known to be malleable, and predictions liable to reinterpretation. Stevens brings up the American preacher William Miller, who in the 19th century predicted that the second coming of Jesus Christ would take place in 1843 or 1844.

“People stood on rooftops waiting for the rapture, which was when they were going to be taken up to heaven,” Stevens says., “The rapture never happened, but the group persisted.” After a period known as the Great Disappointment, the Adventists emerged, and with them, the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

There is a sense of near-constant reinvention in Raël: The Alien Prophet—throughout the decades, Vorilhon relocates. He consistently wears white, but moves on from the shoulder-padded robes of his beginnings to tank tops and pants.

And through it all, five decades after Vorilhon’s interview with Ardisson, a question still resonates: “Don’t you think,” Ardisson asks the self-styled prophet in the 1994 clip, “that it’s because you never knew your father that you went looking for one among the aliens?”

At that, Vorilhon looks to the side, at nothing in particular. “That’s Freudian psychology,” he says. “I don’t think so, but…”

Ardisson quickly moves on. This is all we get. On that point, the prophet has no answer.