Clarence Thomas Cited My Work In His Affirmative Action Opinion. Here's What He Got Wrong.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a concurring opinion in support of the Supreme Court's June decision striking down affirmative action in college admissions.

I gasped when I saw the text.

“Hi, I just read the affirmative action decision and saw Clarence Thomas cited your book in a footnote in his concurrence to totally misinterpret your work. I’m sure I’m not the first person to share this, but just want the record to show, I am appalled.”

I, too, was appalled that a book I’d written about the impact of education was used to uphold the Supreme Court justice’s anti-affirmative action argument. We are in a sad moment when cherry-picked information now passes as fact.

Thomas’ concurrence in the court’s June 29 decision, which struck down affirmative action in college admissions, argues that “meritocratic systems have long refuted bigoted misperceptions of what black [sic] students can accomplish.” The concurrence cites details from my book about Dunbar, an extraordinary, academically rigorous, once legally segregated high school in Washington, D.C., where Black students thrived for a century. What a shame to see that a story about the greatest generation of African Americans, who defied expectations, was being used to support a position that would have kept many of them from reaching their full potential and succeeding in America.

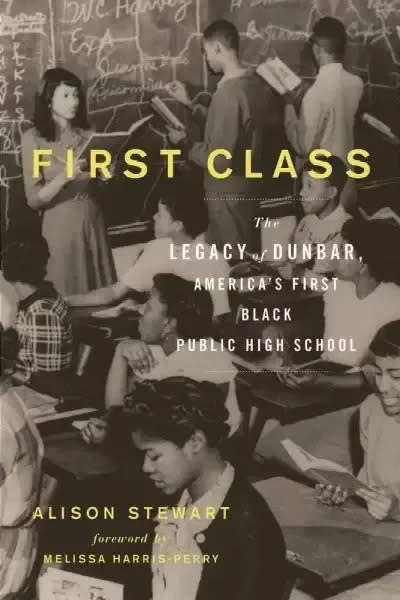

I met the sender of that text, attorney Jeff Tignor, when researching my book, “First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School.” I interviewed his father, Dr. Gregory Tignor, a top student at Dunbar in the 1950s, who then excelled at Yale and is now a professor emeritus at his alma mater. His grandfather, Madison Tignor, was also a Dunbar grad and a respected educator who taught my parents at the high school in the 1940s.

Founded in the basement of a church in 1870, Dunbar was once described by the NAACP as “the greatest Negro high school in the world” and became a famous incubator for glass ceiling breakers.

In his argument upholding the myth of pure meritocracy, Thomas cites some of the success stories from “First Class,” including Robert Weaver, the first Black member of a presidential Cabinet; Benjamin O. Davis, the first Black general in the U.S. Army; and William Hastie, the first Black federal judge. He argued intellect is enough for Black students to succeed, and Dunbar proved that.

Dunbar nurtured talents like Dr. Charles Drew, the modern blood bank founder, artist Elizabeth Catlett, jazz great Billy Taylor, and Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton. Dunbar, much like the true purpose of affirmative action, was about access and opportunity, not pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps. Dunbar provided a first-class education and guidance when these young Black boys and girls weren’t thought of as scholars by white America.

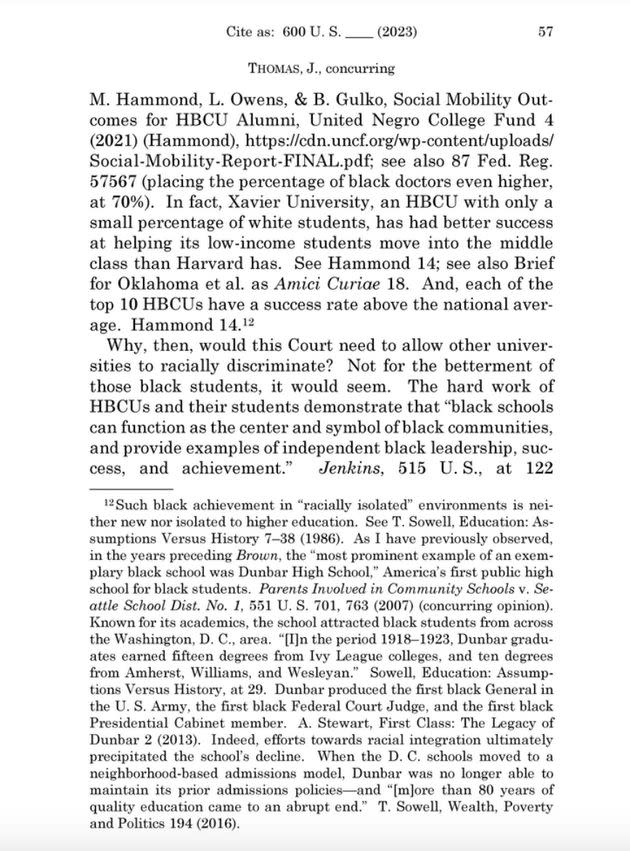

Page 57 of Thomas' concurrence, which cites "First Class," the author's book.

Taught by highly educated Black professionals who couldn’t get work in their respective fields due to Jim Crow (doctors, lawyers ― even the first Black graduate of Harvard was a principal at Dunbar), students were hypereducated by the hypereducated. It was an example of what is possible if children are invested in and supported.

At one point, 80% of Dunbar graduates went to college. Thomas cited the statistic to argue that Black students can achieve. No argument there. But the idea that these students simply applied to schools, were recognized, and received engraved invitations to elite institutions is a fantasy.

When Anna Julia Cooper, one of the great educators and thinkers of the 20th century, was the school’s principal in the early 1900s, she would contact colleges and universities to let them know she had qualified “Negro” candidates. These schools weren’t actively looking to embrace “colored” students. Without Dunbar and Cooper, her students would not have been accepted at Harvard, Brown, Amherst and Williams. She took action, affirming that these young scholars were worthy of consideration ― not that they be given preferential treatment.

And when they got to whatever college or university they were accepted into, they were on their own. Before he became the first Black graduate of the Naval Academy, Wesley Brown was hazed relentlessly and given demerits regularly. A young cadet named Jimmy Carter stepped in, telling racist classmates to leave Brown alone.

When Mary Hundley went off to Radcliffe in 1914, she was not allowed to live on campus, and a dean condescendingly suggested that the brilliant young woman should also do some cleaning while there. When Hundley returned home, she taught French at Dunbar and worked on college placement, negotiating on students’ behalf with admissions offices. Hundley’s papers are at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute, including a letter imploring Sarah Lawrence College to reconsider a student for the class of 1951. The response was, “We accepted one of yours.” It was my mom.

As Gregory Tignor told me, “Dunbar provided a magnificent education. I was well prepared for my alumni interview and my undergraduate career at Yale. What it did not provide was access to the prevailing power structure. Its ruthlessness was an adjustment for many of us who were accustomed to the camaraderie and compassion of Dunbar.”

The graduates of Dunbar fought to break barriers by, yes, being great, but also by being present: being in the room, at the table, pulling up a chair to the table and sometimes building the table.

The graduates of Dunbar fought to break barriers by, yes, being great, but also by being present: being in the room, at the table, pulling up a chair to the table and sometimes building the table. It took more than their wits and brains. It took others to help them achieve, and they in turn helped others.

Several of the lawyers who argued Brown v. Board of Education were Dunbar graduates, as was Charles Hamilton Houston, the architect of school desegregation and a cum laude graduate of Harvard Law School in 1923. He had been treated so poorly after returning from World War I that he vowed to change the system.

These students were able to excel also in part because of their solid, Black, middle-class parents who could actually make a living working in and around the government. The not-that-pleasant but real issue of colorism was present, and not just on the surface level. Especially early on, many students at Dunbar were fair-skinned ― descendants of white people who allowed their offspring to learn to read at a time when their darker-skinned peers were legally banned from doing so. The lighter-skinned students weren’t superior as human beings, they just had superior advantages.

Yes, many people have advantages. Saying that they don’t is unreasonable. I sat on the board of a competitive university and listened as the athletic department claimed its slots for the freshman class, as did legacies. There should be a mix of students: first-generation, rural, urban and all interpretations of the rainbow. That takes work.

I learned of Thomas’ (or his clerk’s) misreading of Dunbar’s legacy on the eve of July 4, shortly after leaving the African American History Museum. There, I read about how much a young boy had sold for and saw wood remnants from a slave ship. I even saw photos of a few Dunbar grads, including the first Black general in the U.S. Army. The visit to the museum also made me think about a recent documentary that noted how the University of Alabama’s Greek system didn’t desegregate until 2013, the same year “First Class” was published.

There’s a striking reveal in the museum where visitors enter a room to see a wall-sized quote from the Declaration of Independence about all men being created equal, while a real shackle sits in the foreground. Thomas’ anti-affirmative action concurrence ends with the same quote.

The Fourth of July is my birthday, and I spent it writing this.

Everything I have is because of the pain and sweat of sacrifice of those who came before me, including my grandmother, who was born in 1899 on Juneteenth, the other independence day. She often told me stories about her father, Samuel Pride, who was born enslaved, yet later went on to college and helped establish one of the first colored high schools in Charlotte, North Carolina. The Klan threatened my great-grandfather, so much so that Professor Pride stayed up many nights sitting on the porch with a shotgun on his lap. Education was that important ― people fought for it and died for it.

Education has always been and will always be a prized possession for Black Americans, for whom it was once illegal. How sad is it that our courts are again using the law to keep it out of arm’s reach for talented children? We as a country owe a lot to Dunbar and institutions like it, also cited in the opinion. Dunbar shouldn’t be used to support an argument that opposes what it stood for and stands for still: opportunity. Access. A chance.

To argue that brilliance is enough for a member of any marginalized group to achieve equity doesn’t bear out in reality. If it did, our boardrooms, campuses and courts would look a lot different. Consider that the Supreme Court, founded 234 years ago, seated its first Black woman as a justice just last year. So maybe we won’t need affirmative action 234 years from now. But today, the doors to our country’s power structures remain closed and hidden for too many. Affirmative action can at least unlock the door or reveal where the door even is.

I can’t do anything to remove my name from this decision, and that’s frustrating. I’ve done a lot of reporting in many 21st-century high schools, in addition to a decade working on my book, researching the history of Black education and interviewing elderly Dunbar graduates. Everything in this essay is also in my book, as is the detail in the court’s decision. Dunbar is mentioned on one page, but seeing these stories taken out of context is, in my opinion, wrong. The truth is important. Context is important.

All I can do is use more words to set the record straight. Going forward, I would ask Thomas that when it comes to supporting his thoughts on affirmative action, “Please,” as the kids say, “keep my name and Dunbar’s out of your mouth.”

Alison Stewart is host of “All Of It with Alison Stewart,” WNYC’s daily live afternoon program. She is also the host of the monthly book club GET LIT WITH ALL OF IT, a partnership with The New York Public Library. Stewart has spent more than two decades reporting for NPR, PBS, ABC, and MSNBC. She’s a contributor with The Atlantic LIVE and the author of “First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School.”

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.