Clarence Thomas’ Defenders Say He’s Just Like Ruth Bader Ginsburg

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas prides himself on sticking to the plain text of the Constitution, statutes, and regulations, but there is something about the definitions of simple words like reimbursements and gifts that appear to have eluded him. As I explained in a previous article on Slate, Thomas’ recently filed financial disclosure report for 2022 included a weeklong luxury vacation for himself and his wife, Ginni Thomas, as the “guests” of Harlan Crow, including “flights to and from Adirondacks by private plane and lodging, food, and entertainment.” Remarkably, however, Thomas listed the trip under “reimbursements” not “gifts,” saying that he was following July 10 “advice from the staff of the Judicial Conference Financial Disclosure Committee.”

The classifications make a serious difference. Gift disclosures must provide values; reimbursements need not. Thus, Thomas’ choice of categories, which defies the plain meaning of the two words, effectively concealed the value of his vacation at Crow’s private resort.

Thomas’ report added a note claiming that he was acting consistently “with previous filings by other filers,” but he failed to provide dates or names. None of the other justices’ 2022 reports include expense-paid vacations as reimbursements. Instead, as would be expected, they list only speaking engagements and similar events at law schools and conferences.

Thomas’ account of advice from the Financial Disclosure Committee is baffling at best, given the acknowledgment that he and his wife were Crow’s “guests” at his resort. The Judicial Conference’s own Guide to Judiciary Policy defines reimbursement as any payment to cover travel-related expenses “other than gifts.” The definition of gift includes “anything of value, unless consideration of equal or greater value is received by the donor, including food and beverages consumed in connection with a gift of overnight lodging.”

I sent inquiries to Thomas’ chambers; Judge David Bunning, the chair of the Committee on Financial Disclosure; the director of the Judicial Conference; and the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, requesting a copy of the July 10 advice to the justice (or a summary if the advice hadn’t been in writing). There was no response from Thomas’ chambers, Bunning, or the Judicial Conference committee. The public information officer for the administrative office replied that “advice sought by any filer is confidential and we do not discuss that advice publicly.” She did not write back after I asked for confirmation that Thomas sought advice on July 10.

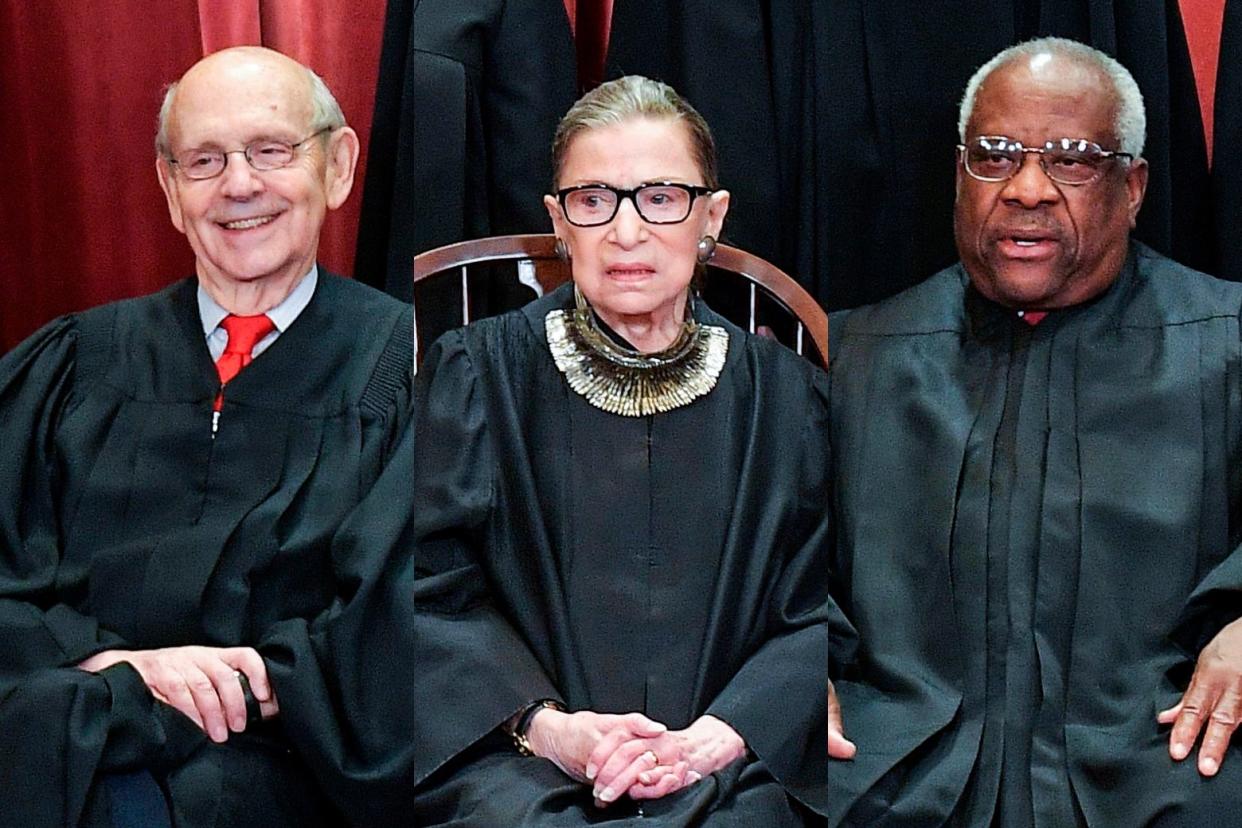

A reply of sorts was posted on X (formerly Twitter) by Mark Paoletta, a friend of and occasional spokesman for Thomas, and an attorney for Ginni Thomas. Paoletta noted that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg took a three-day tour of sites in Israel and Jordan as the guest of Morris Kahn in 2018, disclosing the travel under “reimbursements.” Similarly, Justice Stephen Breyer was flown to a 2013 wedding in Nantucket by David Rubenstein, also listing the trip as a “reimbursement.” Paoletta is right that Ginsburg and Breyer—who, by the way, are no longer on the court, Ginsburg having died in 2020 and Breyer having retired last year—under my straightforward reading of the rule, should have listed these as gifts. He is still incorrect to conflate the episodes.

Critically, Ginsburg was already in Israel to accept a lifetime achievement award from the Genesis Prize Foundation, which paid for her airfare and lodging. The excursion with Kahn was a short side trip, which she scrupulously listed separately (even as she mischaracterized it). Unlike Thomas’ cruises and other vacations with Crow, neither Ginsburg nor Breyer invoked the “personal hospitality” exemption to avoid disclosure.

Nonetheless, both Ginsburg and Breyer clearly misclassified their travels. The trips, as described by the two justices, should have been disclosed as gifts, including their value, rather than reimbursements. Again, Ginsburg and Breyer are no longer on the Supreme Court. Thomas is.

Paoletta also complains that Breyer took “17 trips funded by billionaire Democrat Pritzker family for architecture board under REIMBURSEMENTS on his form.” Those trips were actually funded by the Pritzker Foundation, not the family (the Pritzkers have members in both parties), for meetings related to awarding the Pritzker Architecture Prize. Rather than gifts, they were correctly classified as reimbursements. So were, as I noted on Slate, Thomas’ two Crow-financed flights to Dallas for an American Enterprise Institute conference, for which he was the keynote speaker, and other justices’ expenses for teaching and speaking engagements.

Given Thomas’ famous disdain for stare decisis, it is mysterious, at best, that he relied on two such plainly erroneous precedents, which contradicted the plain text of the applicable rules. In the absence of any further clarification, we can only speculate about Thomas’ reasoning and the apparent approval of the committee staff.

As every practicing lawyer understands, the validity of advice depends on the accuracy and candor of the information provided by the client. Unfortunately, Thomas, along with everyone else involved, has refused to make the July 10 communications public. Consequently, there is no way to know exactly what he told the Financial Disclosure Committee about the nature of his flights on Crow’s private plane.

Perhaps Thomas simply listed the three destinations, without distinguishing his vacation from the American Enterprise Institute conference. Or perhaps his descriptions were incomplete in some other way. Even Paoletta did not suggest a description of Thomas’ vacation as something other than a gift as defined in the Guide to Judiciary Policy, which therefore requires disclosing a “good faith estimate of the fair market value.”

In any case, it is unlikely that the “staff of the Judicial Conference Financial Disclosure Committee” would have audited or closely questioned a Supreme Court justice.

Everyone can make mistakes on forms, of course, evidently including Ginsburg and Breyer. In contrast, however, Thomas’ misclassification was admittedly intentional. He announced on April 7, 2023, one day after the first revelations by Propublica, that he was planning to begin disclosing his Crow-financed trips, and he had from then until Aug. 9, when he actually submitted his report, to decide how to do it. (The report was released to the public on Aug. 31.)

As Thomas’ explanatory note conceded, he considered listing his Adirondack vacation as a gift, but purposely chose to call it a reimbursement, which consequently enabled him to withhold its value.

That wasn’t a misinterpretation of the instructions, and it wasn’t an inadvertent slip-up, as Thomas has claimed for other nondisclosures. It was the deliberate omission of information that the public has a right to know.