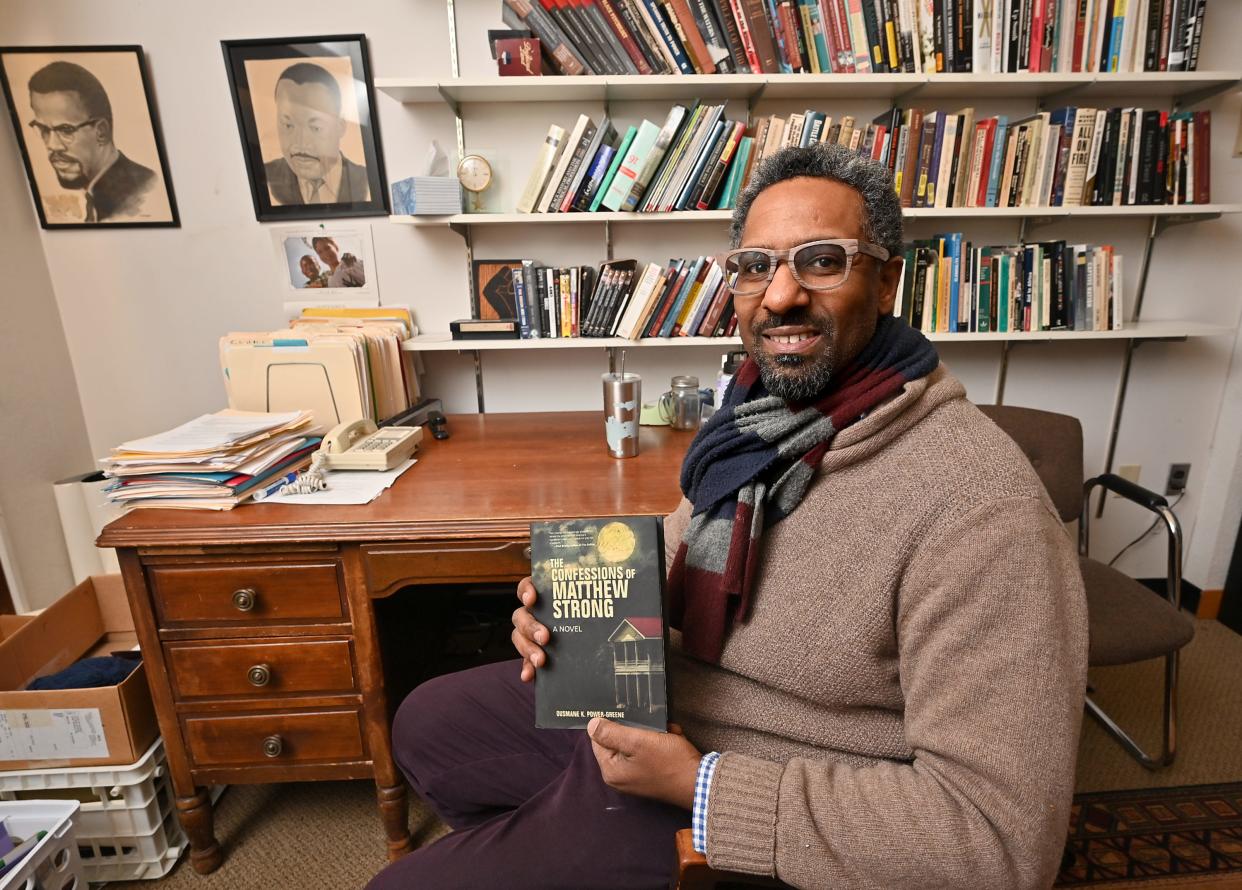

Clark professor's debut novel digs for the seeds of racial violence

WORCESTER — Growing up in 1980s Westchester, New York, one of Ousmane Power-Greene’s first encounters with the concept of racial violence was learning about the Atlanta child murders. The fact that all the victims were Black, in an area rife with racial tension, had many suspecting the killings were racially motivated.

“That idea, verified or not, was very formative in my young life,” said Power-Greene, now Program Director of Africana Studies and an associate professor of History at Clark University, “it was the first moment that I came face to face with this idea that because I’m Black, someone might actually try to kill me.”

White supremacist ideology and the danger it poses, said Power-Greene, is often dismissed as limited to a small group of people with extreme ideas in certain parts of the country. Through his new novel, “The Confessions of Matthew Strong,” he said he hopes to better educate people about this phenomenon.

“The ideas of white supremacy are everywhere in the United States,” he said, an example being the 2008 burning of the Macedonia Church of God In Christ in Springfield in response to the election of President Barack Obama. Despite being an overt act of racial violence in a supposedly liberal part of the country, he remembers how “there was almost zero media coverage — it was covered briefly and sort of disappeared.”

Switching gears

Until now, Power-Greene’s published work, focusing on African-American history and America’s struggles with race, has consisted entirely on nonfiction historical analysis. “Confessions” is his first published foray into historical fiction.

“When it comes to writing historical work, your basic goal is to find external evidence like documents,” he said, “when you’re writing fiction it’s the opposite — you have these fragments of ideas and you’re imagining, which is literally going internally, for fictional people’s motives.”

For this, Power-Greene draws on family history, and how his grandmother’s family, originally from Alabama, moved north to fleeing racially motivated violence. “For me, going through this process has forced me to tap into that understanding about racial violence and how racial terror has functioned for Black people,” he said. “It feels very personal.”

Stranger than fiction

The story centers around a Black woman named Allie Douglas, a philosopher who gets caught up in white supremacist Matthew Strong’s plots to ignite an insurrection.

When Power-Greene first began outlining the story more than 14 years ago, the idea of American citizens plotting an insurrection seemed firmly grounded in the realm of fiction — “but then Jan. 6 happened,” he said. His editors and prerelease readers were shocked, he recalled. “As authors we imagine the future.”

The insurrection of Jan. 6 drew people from across the country, he said, “many people are not even aware how white supremacy underpins some of those organizations.”

For Power-Greene, that connection between white supremacy and the January 6 is as clear as the image from that day of someone walking through the capital with the confederate flag. “We have seen the long battle against those kinds of symbols," he said, such as confederate flags and swastikas, "but it’s not over as long as people continue to use those symbols to represent themselves."

“The novel looks at the emergence of the contemporary white power movement,” said Power-Greene, and its basis in returning to an idealized past. “People like Allie Douglas who represent progress,” he said, “demonstrate the demise of what was once the white racial order. These groups mask and code their language to lure people in, reframing history,” he said, such as presenting the Confederacy as the romanticized "lost cause" in the name of state’s rights.

Ingrained in the system

Discussions around racism and violence in the news have not centered around overt white supremacists as much as institutional racism inherent in systems such as law enforcement, said Power-Greene. Michael Brown, George Floyd, and most recently Tyre Nichols, all serve as examples of who certain institutions do and do not protect, he said, "where certain people are treated and viewed by those who work for the institution differently and sometimes violently."

The fact that majority of the officers involved in Nichols' murder were black changes little, according to Power-Greene, and that situation was no less an example of white supremacist underpinnings throughout law enforcement. "The reality is that Black people in a variety of circumstances have committed horrible acts against other Black people," he said, going back to black overseers on plantations and even Black slavecatchers. "It goes back to how the police department — whatever the race and creed of the individual members — sees Black people and the assumptions they make."

Hope for the future

“Confessions” has been a long time coming, said Power-Greene, and the novel reflects what’s happened over years since he started writing it. “By the time the story was finished, we had opened the door to known white supremacists and the alt-right,” he said, with blatant racism finding its way into politics once again.

While that may be discouraging, as an educator, Power-Greene looks to classrooms as an indicator of the future, and what he says is uplifting.

Sitting in a fifth-grade social studies class during a school visit, Power-Greene heard the students reflect on how past laws were racist and sexist, “a broad diverse group of kids saying this was ridiculous or absurd,” he said, “it gives one hope.”

This article originally appeared on Telegram & Gazette: Clark professor Power-Greene’s eyes racial violence in new novel