Classrooms have become political battlegrounds in Florida. Will it intensify this year?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Adele Valencia remembers well how Ms. Brand, who taught fourth- to sixth-grade gifted students at Pinecrest Elementary School, encouraged her to read books she otherwise wouldn’t have opened, including some about the Holocaust.

In fact, Roberta Brand invited Holocaust survivors to her class so students could grasp their suffering. She also taught them about the 1994 Rwandan genocide — the massacre of up to a million people because of their ethnicity — that had just happened and hadn’t entered their textbooks.

“Those are really challenging things for anyone to take on, especially small children, but I think they were introduced in ways that were developmentally appropriate and that really expanded my horizons to understand how wrong it is to victimize other people who are different and not speak up for people who are persecuted,” she said. “She was the kindest and most inspiring educator.”

Valencia, 40, an attorney, so enjoyed her years at Pinecrest Elementary that she and her husband planned the purchase of their home based on the school zone, so they could send their children — Lily, a 7-year-old who will start second grade, and Julia, a 5-year-old who will begin kindergarten — to that same school.

But now she worries her efforts were in vain: “I am concerned about how the potential state overreach is impacting our local district.”

She’s not alone.

As they prepare to start a new school year over the next week or two, many Miami-Dade and Broward public school teachers, students and parents are anxious over returning to a classroom, the place where some of the most controversial laws signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis will play out. Laws or new rules by the Florida Department of Education dictate what can be taught about race, gender identity and sexual orientation, empower parents to challenge school library books and prohibit teachers from asking students about their preferred pronouns.

READ MORE: Book bans are growing in South Florida schools. You’ve probably read some of these books

“It feels lousy. It feels uncertain. It feels frightening,” said Richard Judd, who has taught 11th- and 12th-grade history and government for 23 years at Nova High School in Davie. “There’s a lot of mystery and confusion.”

DeSantis, who is running for the Republican presidential nomination in the 2024 election, and his supporters, including conservative groups like Moms for Liberty and County Citizens Defending Freedom, say they’re giving parents who align with their views more of a voice in their child’s education.

“Parents’ rights have been increasingly under assault around the nation, but in Florida we stand up for the rights of parents and the fundamental role they play in the education of their children,” DeSantis said in a 2022 release announcing he had signed the “Parental Rights in Education” bill, which bans the teaching of gender identity and sexual orientation from kindergarten to third grade in Florida public schools and requires “age-appropriate” instruction in older grades.

DeSantis and his supporters also cite a ‘woke’ liberal agenda in public schools and preach a return to a classical education, although critics say that’s imbued with white Christian teachings and opposition to certain topics about race and LGBTQ communities.

“There is evil in this world and we are fighting it here today. We are going to do it because God does not make mistakes with our children,” Randy Fine, a Brevard County Republican legislator told a Tampa audience in May. The crowd had gathered to watch DeSantis sign into law five bills, including the bill that restricts the use of pronouns in schools.

Some teachers, students and parents also pointed to the recent expansion of a tax-funded voucher program that allows families, regardless of income level, to get money from the government to attend a private school, providing the school is part of the program. Public school advocates say this could significantly impact local districts.

READ MORE: What to know about Florida’s new private school voucher program that has no income limits

“This is going to be tough on us,” said Peter Licata, the newly hired superintendent for Broward public schools, the nation’s sixth-largest school district.

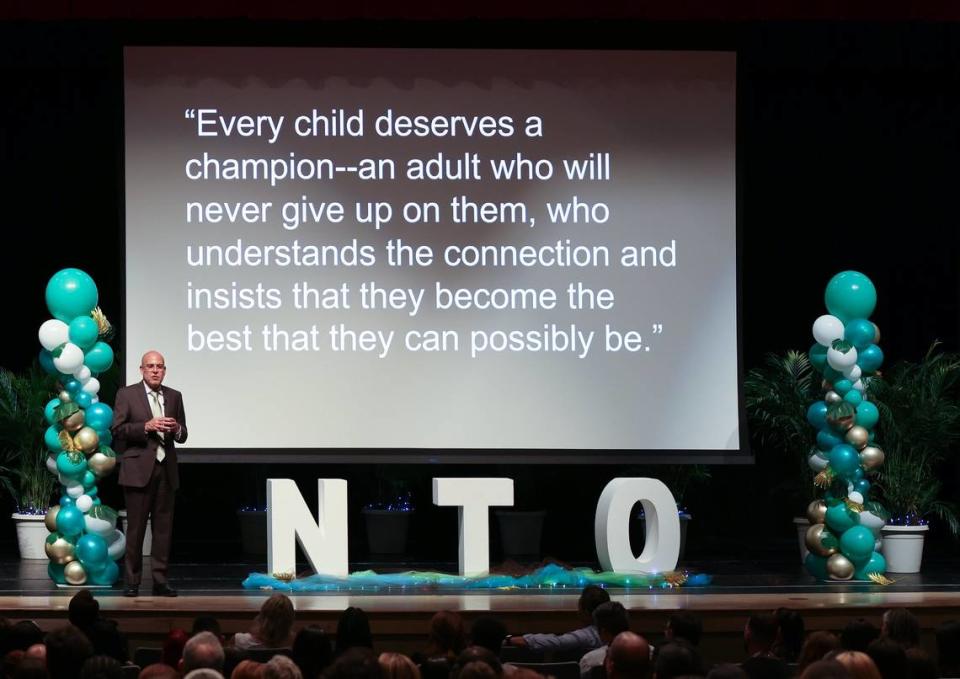

Classrooms as political battlegrounds

In this year’s session, the Legislature expanded the “Parental Rights in Education” law, which critics have labeled the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, restricting gender identity and sexual orientation lessons from third grade through eighth grade. Moreover, a state education rule enacted this spring expanded the prohibitions through 12th grade, unless the instruction is part of a reproductive health course or is “expressly required” by the state’s academic standards.

READ MORE: Florida officially limits gender, sexual orientation instruction in all school grades

The new law also restricted school employees from calling students by their preferred pronoun, if it differs from the one assigned to them at birth, and made it easier for parents to challenge instructional material and school library books.

That’s led to book challenges that have garnered national headlines, including the decision in May by the Bob Graham Education Center in Miami Lakes to remove from its elementary school library shelves three books and the poem “The Hill We Climb,” written by Amanda Gorman and recited by her at the inauguration of President Joe Biden on Jan. 20, 2021.

One parent at the school, which has grades K-8, had complained about the books and poem, saying they contained references of critical race theory, “indirect” hate messages, gender ideology and indoctrination. (The parent also complained about another book, “Countries in the News: Cuba,” which the school decided would remain available to all students.)

READ MORE: Poet speaks up after Miami-Dade school bars elementary students from reading her poem

For Valencia, the Pinecrest parent, the brouhaha over the books detracts from the significant issues facing schools.

“I think most teachers are in their profession for the right reasons, and they’re struggling mightily from the deficits we all have from the COVID years to get their kids to understand and master some of the most basic concepts we need to function, like reading and math,” she said.

“So to me — these controversies like the notion that we’d spend any energy banning a poet like Amanda Gorman — sort of misses the point and distracts from the real challenges we have.”

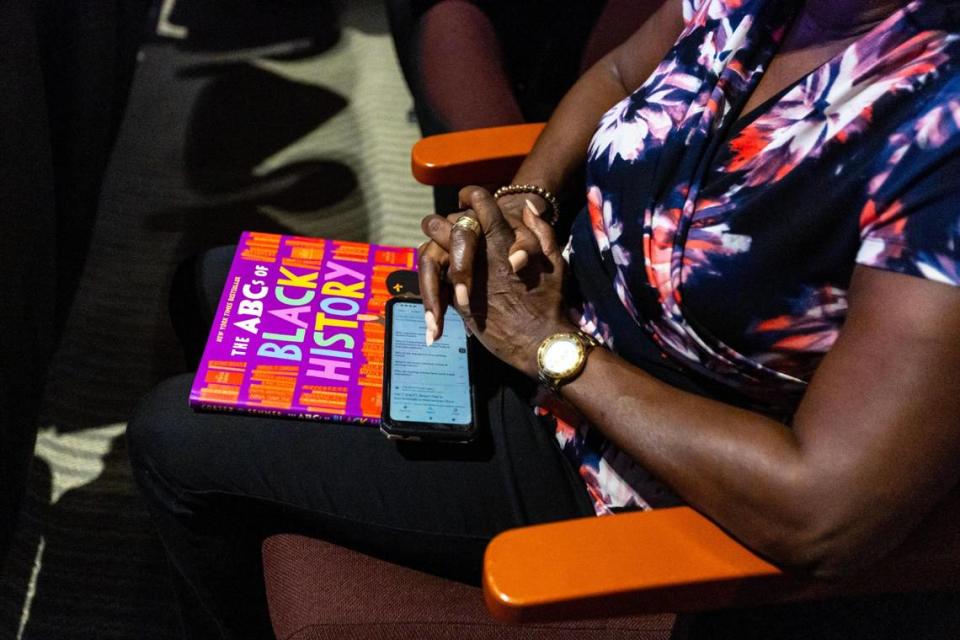

Black history controversies

Last month, the Florida Board of Education, as part of its review of social studies books, adopted new standards for teaching Black history in public schools. The standards were widely criticized for requiring middle school lessons to include “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied to their personal benefit.” Another section of the standards that drew backlash was comparing anti-Black violence with acts of Black resistance.

READ MORE: Teachers enraged that Florida’s new Black history standards say slaves could ‘benefit’

The controversy over the Black history curriculum followed a decision by the College Board earlier this year to leave out references in its new AP African American Studies course to the Black Lives Matter movement and slavery reparations, among other topics. The Board’s decision came after DeSantis announced the state had rejected the course.

READ MORE: Black leaders blast College Board’s changes to AP African American Studies course

Susan Boundy, who taught eighth-grade history at Ruth K. Broad Bay Harbor K-8 Center for 40 years until she retired in 2020, said the new standards shocked her.

“I’m just amazed that we’re no longer supposed to be teaching things that are based in reality. It was very upsetting,” she said. “African American history, just like any history, must be document-based, not opinion-based. Regardless of how you feel after learning the facts, you can’t change any facts.”

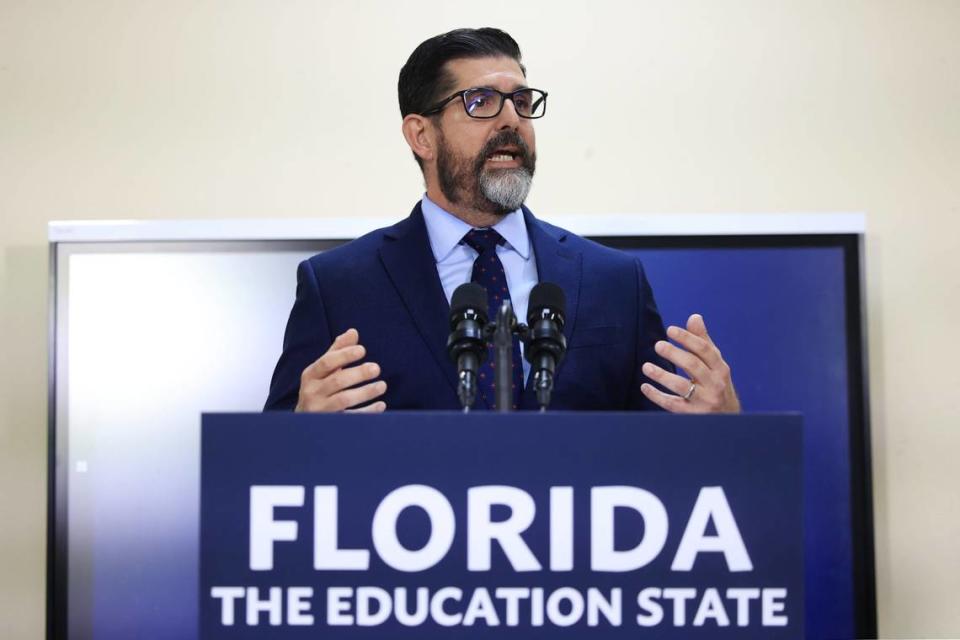

Stephen Hunter Johnson, the father of a 12-year-old who will enter the seventh grade at iPrep Academy North, was disappointed to learn that Florida Education Commissioner Manny Díaz Jr. had pulled out of a town hall Thursday evening in Miami Gardens to discuss the new standards. Díaz posted on social media that he was busy visiting schools.

READ: Florida education commissioner pulls out of Black history town hall in Miami Gardens

“I feel dismayed and disrespected as a parent. I feel dismayed and disrespected as a Black Floridian.,” Johnson told the Herald.

He said his son has experienced racism in his school. “We’ve had to have conversations about the ‘n-word,”’ he said. “And these standards don’t help any of that. Thank God, I have a resilient kid.”

Judd, the longtime high school history and government teacher at Nova, said what disturbs him are the penalties and consequences the state has levied on teachers who violate the new laws and rules. He said he doesn’t know yet how this will impact his teaching.

“I have no idea,’’ he said. We’ll see.”

School starts Monday, Aug. 21, for Broward public schools; in Miami-Dade, school starts Thursday, Aug. 17.

To ease hesitations about the standards, Miami-Dade Schools Superintendent Jose Dotres said he’ll seek feedback from teachers and coordinate specific lessons with them.

“I know there have been concerns about them and we have to work through these,” he said. “We have to work hand-in-hand with teachers so that they’re able to provide instruction that’s comprehensive and that they feel properly trained so they feel comfortable in teaching.”

Jamal Victor, a rising senior at Miami Edison Senior High School, said he sometimes feels like he learns more about Black history on TikTok than in class. The other day, he said he saw a video about Robert Smalls, a South Carolina slave who escaped from Confederate forces while working on a transport boat in Charleston Harbor before the Civil War. He later became a member of the U.S. House of Representatives and was influential during Reconstruction after the war.

Smalls eventually bought the mansion of his former slave owner; the Robert Smalls House is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places in Beaufort, South Carolina.

“I had never heard about him,” he said. “Teachers should talk more about that. Teachers say they teach about what’s important. That’s history. That’s important.”

U.S. Rep. Frederica Wilson, D-Miami Gardens, who was principal of Skyway Elementary School in Miami Gardens and a Dade County School Board member before being elected to Congress in 2010, has long advocated teaching Black history in Florida’s public schools.

She was instrumental in getting Florida lawmakers to pass a law in the 1990s to require the state’s public schools to teach African American history, and she pushed the School Board in 1995 to create the first Black history curriculum in Dade Schools.

She was not happy when she learned of the new standards for teaching Black history: “It’s clear that the State Board of Education made a ludicrous attempt to whitewash history and revise the truth about the Black experience in America. But I think the teachers and the students and families of our state are not stupid. They know that enslaved people were brutalized.”

LGBTQ students at center of culture wars

The teaching of gender identity and sexual orientation is another contentious issue, particularly since the state law signed by DeSantis in the spring prohibits teaching about these topics through eighth grade, and the new state rules expand the prohibitions to 12th grade, unless part of a reproductive health course.

The contentiousness played out Tuesday when the Broward School Board spent nearly four hours listening to public comments about whether to approve a resolution recognizing June as Pride Month and another resolution designating October as LGBTQ History Month.

“I can’t begin to say how today feels like the ugliest anti-LGBT environment in a very long time,” activist Michael Rajner told the South Florida Sun Sentinel. “It’s been difficult to sit in the room.”

“What we need to shut down is this labeling that you cannot have more than one opinion,” countered Broward School Board member Brenda Fam. “Not agreeing with something is not hateful. It’s having an alternative view.”

Some raised concerns that such designations broke the law, although Marylin Batista, general counsel for the board, said they didn’t.

“These resolutions are not curriculum. These are just ways to show support for everyone in our community,” said School Board member Debra Hixon, a former teacher who said she served as one of the first advisers of a Gay Straight Alliance club in the 1990s. “We cannot educate our students if they don’t feel safe or loved.”

In the end, the board adopted the resolutions, which differed from what happened with the Miami-Dade School Board last September. In a meeting that brought out a contingent of Proud Boys — and where one side likened the resolution to recognize October as LGBTQ month as student indoctrination while the other invoked the Nazis forcing gay and lesbians to wear a pink triangle badge — the Miami-Dade board voted 8-1 against recognizing the October designation. (The previous year the board voted 7-1 to recognize it.)

READ MORE: After debate citing indoctrination and Nazis, Miami-Dade School Board rejects LGBTQ month

Artemis, a transgender student at Jose Marti MAST 6-12 Academy in Miami-Dade who asked the Herald not to disclose her last name because she hasn’t come out to her family, can attest to how the anger in the board room is affecting the classroom.

She said she started questioning her gender in sixth grade. By eighth grade, she came out to her partner at the time and friends. She’ll start eleventh grade this fall.

“It’s scary,” said Artemis, 15. “I fear for myself but also for little queer kids who may be discovering themselves.”

She plans to be president of her school’s Gay Straight Alliance Spectrum Club in the new school year. “I want to create at least a small space where students feel safe to be who they are,” she said. “I hope I’m able to.”

Miami-Dade Superintendent Dotres said the district would focus on valuing “the individuality and identity of our students.”

“We’ve always done it and we will continue to do that,” he said. “If there are laws that restrict certain instruction, we have to follow the law. But that doesn’t take away from our responsibility to create environments where students have particular needs or interests feel supported.

“When those two items conflict, that is where I rely heavily on our counselors and district staff to be able to work with the student, the family and the school to find an approach that will be the best for the student and will provide support,” Dotres said. “I believe in the power of having conversations.”

Book challenges on the rise

As part of the expanded “Parental Rights in Education” law, one parent or community member can object to instructional material or a school library book. The law requires the book or materials to be removed within five days of the objection and remain unavailable to students until the issue is resolved.

Kasey Meehan, the Freedom to Read program director at PEN America, a New York-nonprofit that advocates for freedom of expression, said book banning has dramatically increased since the pandemic nationwide but particularly in some states like Florida. Popular challenges include books that have LGBTQ characters, explore race and racism and include any mention of sex.

Broward Public Schools received one book challenge in the 2020-21 school year and one in the 2021-22 school year. In the most recent school year, it received 12. Miami-Dade Public Schools received no book challenges in the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years. Last year, it received six.

Meehan said PEN sees any efforts to restrict books as problematic, whether it’ a temporary decision to remove the book while a final decision is made, a decision to move it upper level grades, a decision to place it behind parental permission, a decision to require a literacy test before reading it or a complete ban.

“Those are all moments where access is banned or diminished,” she said. “They’re all bans to us.”

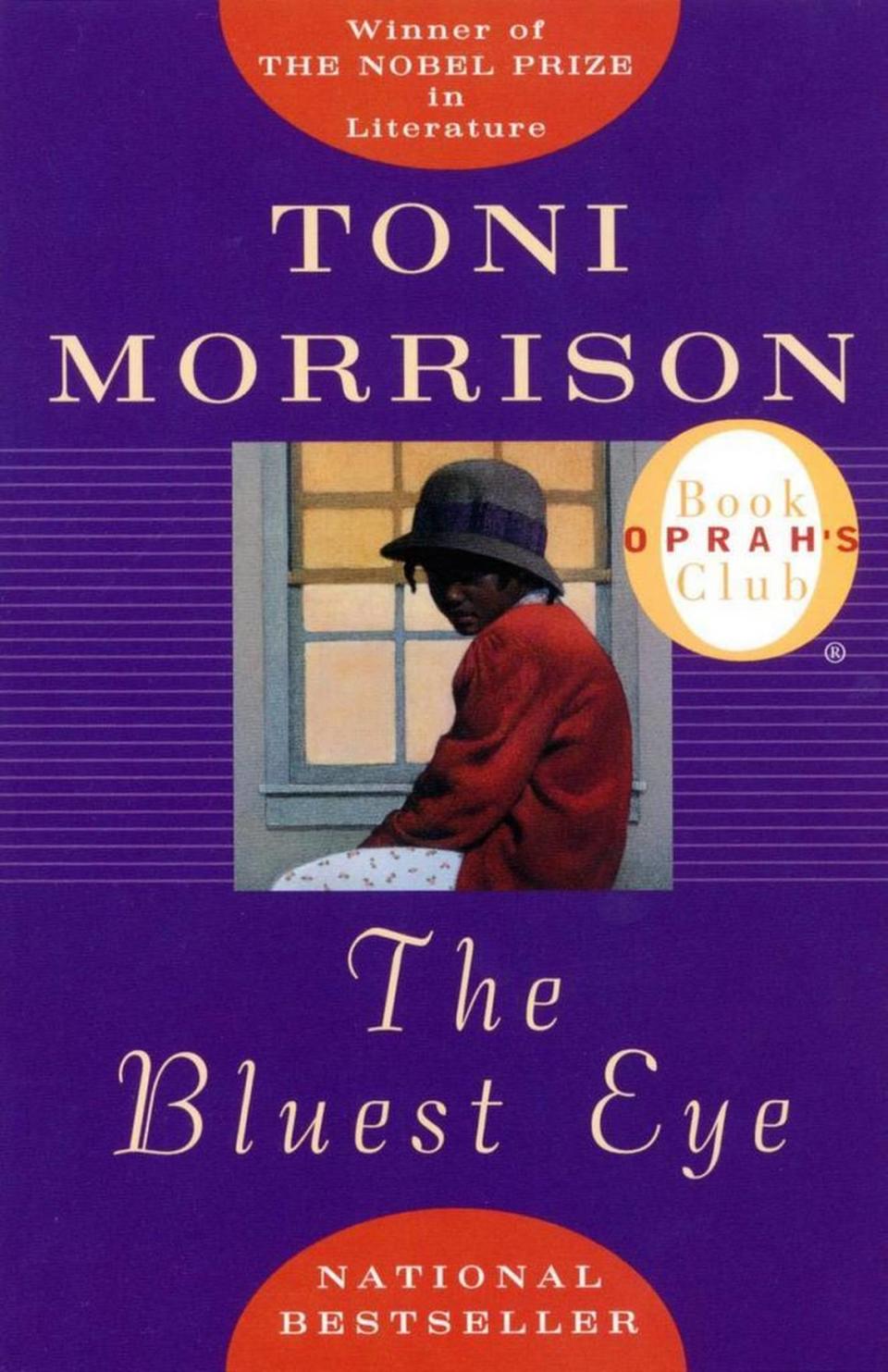

PEN, along with the publisher Penguin Random House, sued the Escambia County School District and School Board in May in federal court. The suit alleges the north Florida district and board violated the First Amendment when the board voted to remove 10 books from school libraries, including ‘The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison. Some of the books were removed altogether while others were removed from certain grade levels. The suit is pending.

How Miami-Dade, Broward deal with book challenges

To deal with book challenges, Broward teachers and administrators listen to each parent’s concerns but use their own judgment, said Licata, the new Broward superintendent.

“We have to make sure we’re following the letter of the law, but that doesn’t mean that when someone calls we just extract things. We go through a process,” he said.

The district, he said, also wants to protect teachers and administrators from the book challenge backlash.

“We’ll hopefully have a clearinghouse here in the district so if a teacher has something that they’re concerned about, they’re not holding the weight,” he said. “Instead, they can send it up to us. We’ll research it and then we send it back to them and say ‘Yes, it’s appropriate’ or not.”

Similarly, Dotres said responses to book objections should never be “solo decisions.” He said multiple experts who know the quality of the material and can decipher whether it’s legal or not should always participate.

Asked if he worried censorship could hurt students, he said that they should be OK if the district handles each challenge “very intentionally and with a lot of attention.”

“We should be able to create the best opportunities for our students,” he said. “We must.”