‘Climate change affects migrating birds,' Oak Ridge Bird Man says

The bird population in North America has declined by almost one-third, nearly 30% since 1970 according to studies performed at Cornell University. Ornithologists have attributed the disappearance of almost 3 billion birds to habitat loss, the rising use of pesticides on farms, declining populations of insects that birds eat, increased killing of birds by hungry feral and domestic cats and climate change.

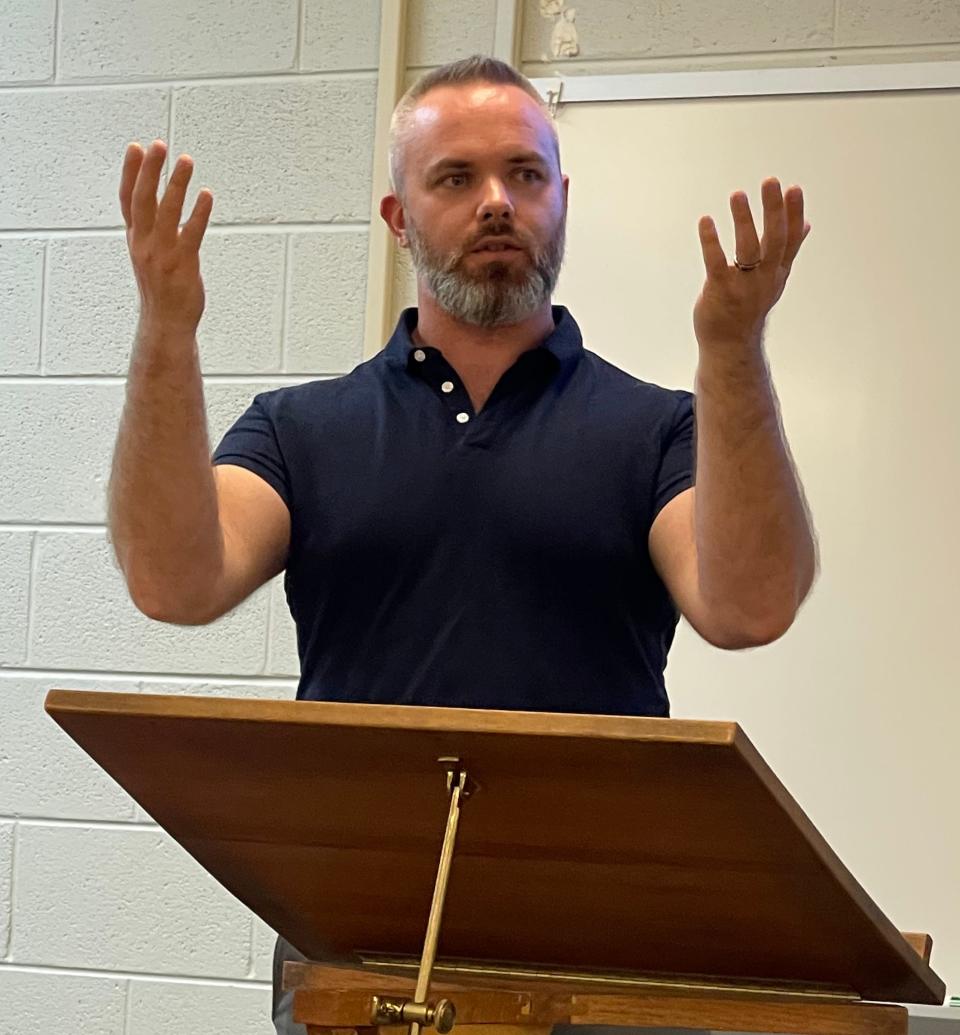

The effect of climate change on migrating birds was a topic of a talk by the Oak Ridge Bird Man to a Friday Lecture class of the Oak Ridge Institute for Continued Learning (www.roanestate.edu/oricl). He will present a series of ORICL classes on Feb. 13, March 12, and April 9 on birds’ sensory apparatus and how it compares to that of humans, avian cognitive abilities and avian social behavior. He will likely tell attendees that if their eyesight were as sharp as a bird’s, “they would be able to read a newspaper held up at the far end of a football field!”

Who is Lucas Coe-Starr and how did he become the Oak Ridge Bird Man?

Who is the Oak Ridge Bird Man? He is Lucas Coe-Starr, a 2006 Oak Ridge High School graduate. He became interested in ornithology while spending one summer on the bird banding team of the Clinch River Environmental Studies Organization (CRESO) at the University of Tennessee Arboretum. He subsequently earned a B.A. degree in biology from Maryville College and an M.Sc. degree in environmental science from the University of New Haven in Connecticut.

“In grad school I studied bird migration for three years while walking on the beach tracking red knots, sanderlings, long-billed dowitchers and black-bellied plovers as they stopped over in Connecticut to refuel themselves,” he said. He jokingly called migratory stopovers “bird truck stops.”

Last December you may have heard on WUOT radio advertisements hawking (no pun intended) the Oak Ridge Bird Man’s bird feeders and nest boxes that he designs and 3-D prints for sale; these items and a variety of wild bird feeds (including seeds, suet and insects) can be ordered through his website at www.oakridgebirdman.com.

He also sells his products on Saturdays at the Oak Ridge Winter Farmers Market in the St. Mary’s Catholic School gym and, starting in April, at the Jackson Square Farmers Market. He also is a landscape consultant who advises homeowners on what plants to grow to attract birds.

Migratory flights and how birds' bodies change

In addition, he has given talks about the effects of climate change on migratory birds. He starts by describing the physiological changes they undergo in response to hormone action before, during and after their long flights to breeding sites with stopovers at places rich in food resources.

“Migratory birds wintering south of the United States keep track of increases in the amount of daylight which indicate when it’s time to get ready to head north and breed,” Coe-Starr said. “As the daylight continues to lengthen, birds experience genetically determined changes in their bodies. Their digestive systems, including their stomach and intestines, will grow physically, making them hungrier because they will need more food reserves to enable their long flight north.”

When migratory birds depart, he added, hormonal changes kick in again.

"The birds’ digestive organs suddenly start to atrophy and shrink relative to their other body systems and their pectoral muscles will become larger to power their flight the whole way. Because the birds don't drink water while in the air, their kidneys also become enlarged to help filter the water produced by metabolizing their fuel reserves.”

Coe-Starr said that “birds know where they are in the air” because they have superpowers such as great eyesight and abilities to sense the earth’s magnetic field and detect air pressure and vibrations. They sense when a storm they should avoid is heading their way and seek out weather conditions that will give them a tailwind, pushing them so they can glide a long way without much exertion toward their destination. If birds feel they are overheating, they know to fly higher where the air is cooler.

Some birds flying north find happy breeding grounds and feeding grounds full of insects in spring and early summer in the Cumberland and Great Smoky mountains, he said.

“Sharp’s Ridge in Knoxville is a great bird watching spot during migration,” he added. He noted that our region has unique habitats at higher elevations that have insects and other environmental variables suitable for birds that would normally breed much further north.

Most bird species breed only once and only during spring and summer in the northern hemisphere, Coe-Starr said.

“It’s mainly during the spring migration that you see a big difference in the arrival times of male and female birds. Males get there first to set up territories. Females arrive later to pick which male each likes best, which territory, or a combination of both.”

Climate change and the impact on birds

So, how is climate change affecting migratory bird populations?

“As global average surface temperature rises, birds are getting smaller,” Coe-Starr said, noting that 40 species are known to have decreased in size, including the red-eyed vireo which is found in East Tennessee.

“Larger birds have a harder time cooling off because they have less of a surface area for heat transfer relative to their body volume,” he explained. “Also, because of rising temperatures, migratory stopovers may have fewer food resources than before. Smaller birds can take better advantage of food scarcity because they don’t have the same demand for energy as larger birds.”

For shorebirds migrating north in the spring, one important stopover for fuel is Cape May, New Jersey, where in April and early May horseshoe crabs lay their eggs, an incredibly energy-rich food source for birds.

“They are like caviar,” Coe-Starr said, “and they spend weeks sucking up the eggs like vacuum cleaners. If climate change causes a northern shift of the horseshoe crab, that will hamstring an entire migratory pathway for dozens of species.”

Another effect of climate change, he noted, is that birds traveling north in the spring are arriving on average one day earlier per decade. It used to be that most spring migrants arrived in the Southeast on March 1. Fall migration occurs at roughly the same time as in previous years, but the migratory period has grown longer as environmental variables shift.

Coe-Starr noted that populations of some birds, like robins and bluebirds, have individuals that stay year-round in East Tennessee as long as they have access to insects and fruit, while others in that same population migrate to warmer or more productive areas during the winter.

“The easiest way to tell whether an individual bird is migratory or resident,” he explained, “is by measuring the length of the bird’s outermost primary feather. If it is longer than the population average, it tends to mean that the bird migrates because it needs longer feathers to travel long distances.”

Coe-Starr said that increasing surface temperatures shift habitats not only to higher latitudes but also to higher elevations, changing the locations of migration stopovers. As climate and habitat zones are pushed off mountain tops and into the sea, he added, migrants may be unable to find sufficient food to fuel their journeys, triggering the loss of whole bird populations.

The Oak Ridge Bird Man spoke about a four-month-old, bar-tailed godwit, a type of shorebird that broke a Guinness World Record a year ago when it flew 8,435 miles non-stop from Alaska to Tasmania, Australia. The 11-day journey without rest or food was tracked by a radio-wave–emitting satellite tag on the migratory bird. The world travelers in the ORICL class were especially impressed.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: ‘Climate change affects migrating birds,' Oak Ridge Bird Man says