Climate change could push produce prices higher, slowing the fight for food justice

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

About seven minutes into Emily Cohen Ibañez's film, "Fruits of Labor," a high school teacher tells students about how, when President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal introduced labor rights to the United States in the 1930s, the measure largely overlooked agricultural laborers.

"Agricultural labor is the only labor in the United States where children as young as 12 years old can still legally work unlimited hours, because they're not protected," the teacher says before the bell rings and the students scatter.

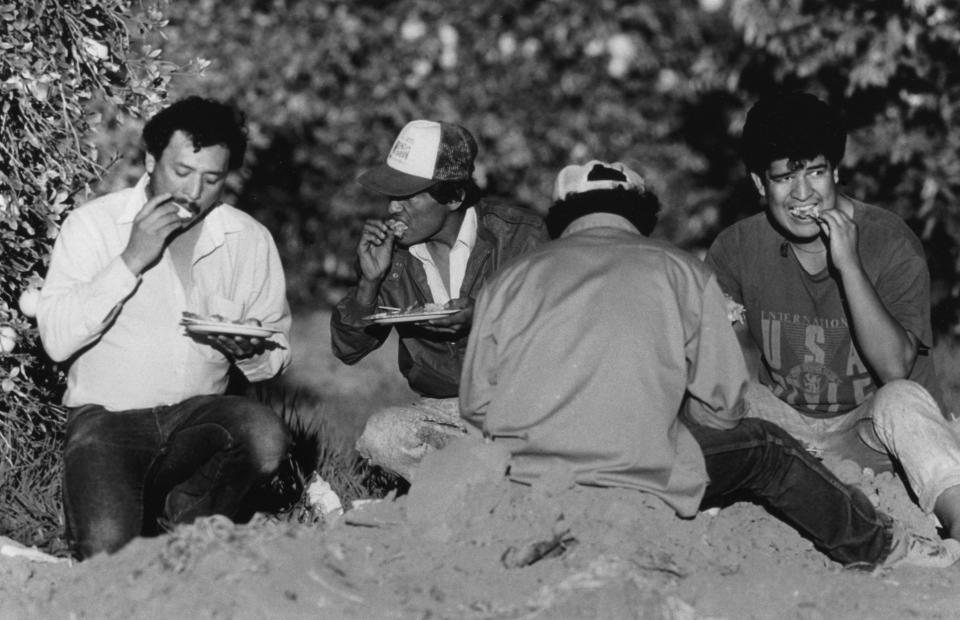

Ibañez describes the documentary as a coming-of-age story, unusual in that it features a working woman of color. The film follows a Mexican-American teenager named Ashley Pavon who works after school in the fields near her home on California's Central Coast, picking strawberries to help her undocumented single mother support their family.

Her relatable journey navigating high school, friendships, prom, dating and sibling dynamics is punctuated by long hours of farm labor, responsibilities beyond her youth and duty-bound sleep deprivation less aligned with the American dream. Her reality is also intertwined with climate change, while aspects of her future hinge on whether pending legislation will address it.

The 74-minute "Fruits of Labor" was screened last month as part of Tucson's Food Justice Film Festival, put on by the Center for Biological Diversity. It joined a 2022 lineup of films showcasing a range of equity issues related to food production: a Native Hawaiian community battling pesticide exposure, Black farmers fighting discrimination from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and an organic gardener helping young people escape gang violence.

Each film highlighted struggles of a different minority community navigating the global food system, and each elucidated a different meaning of "food justice." For Ibañez, who has a doctorate in anthropology and is based in Oakland, the issue is rooted in agricultural labor conditions and wages.

“Food justice is when all people have access to healthy food. The real perversion is you have people picking food they’d never be able to buy," Ibañez said in an interview with The Arizona Republic. "When you have corporations in the berry industry making billion-dollar profits but your workers can’t buy healthy foods or have the time to prepare them and feed their families, that’s a problem."

Agriculture's justice problem

In the film, the teacher in Ashley's classroom describes this problem to her students as one not created by accident.

During his annual address to lawmakers in 1938, Roosevelt reportedly asked Congress to help him "end starvation wages and intolerable hours." The later passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, part of the New Deal, set a 44-hour maximum workweek, a 25-cent minimum hourly wage and banned oppressive child labor in many industries.

The climate value of deserts: Don't think of deserts as wastelands, researchers say, but as a key to our climate future

But it excluded agricultural workers, which Ashley's teacher explained perpetuated a system that keeps many descendants of enslaved people trapped in economic slavery, working the fields, unable to get ahead. It wasn't until the passage of the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act in 1983 that farm workers were brought under the umbrella of fair wages and protections from occupational hazards, such as pesticide exposure, heat illness and safety risks from large equipment. But it didn't put a stop to minors working in the fields.

"Black and brown people were essentially left out of getting worker protection in the United States. That's why we have so many people in our community and even your classmates who work in the fields," the teacher in the film said.

In 2020, nonsupervisory farmworkers made an average of $14.64 per hour, according to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Economic Research Service. But an investigation published last October by The Center for Public Integrity found that wage theft is high among immigrant workers performing low-paying jobs, with many unsure what their options might be after not receiving full paychecks from their employers.

The U.S. Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey estimates that just under 50% of crop farm laborers are not authorized to work in the United States, an increase from roughly 14% in 1990. The USDA notes that the survey may undercount undocumented workers who fear answering survey questions truthfully and it does not account for foreign-born workers with H2-A visas or hired livestock workers.

Climate justice: Climate report draws an arc toward environmental justice, seeking equitable emissions cuts

During the filming "Fruits of Labor," U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement escalated deportation raids in California's agricultural communities under the Trump administration. Ibañez said this forced more U.S.-born teenagers like Ashley out of school and into the fields to help support their families, doing essential work many Americans won't.

"People say it’s unskilled labor. There’s nothing unskilled about it," Ibañez said, sharing that her film crew had to ask Ashley Pavon to slow down while picking strawberries so that they could capture it.

Agriculture's climate problem

Agricultural injustices intersect with the climate crisis in ways that may necessitate restructuring the global food system to ensure continued crop production and access to affordable nutrition, recent reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded.

Scientist members of this international authority on the climate expect weather patterns to intensify with increasing average global temperatures, caused primarily by the emission of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere from burning fossil fuels for energy. Crops and farm workers will be particularly vulnerable to worsening heat waves, drought and flooding when rain falls in heavier but less frequent storms.

Helping the overheated: Amid heat waves, a study questions cooling centers. A Phoenix official says we need more

The scientists predict the agricultural sector will suffer economic damages from reduced crop production and outdoor laborer productivity as relief from heat becomes more elusive.

"Although overall agricultural productivity has increased," the report reads, "climate change has slowed this growth over the past 50 years globally."

Because of this trend, the cost of strawberries and other agricultural products may spike further out of reach for the laborers harvesting them, and for many others in the working class. The USDA Economic Research Service reported that food prices increased 11.4% between August 2021 and August 2022, citing supply chain issues as well as energy, transportation and labor costs for why this number soared above inflation rates.

In addition to being a victim of climate change, agriculture is also a major contributor to it, accounting for an estimated 11.2% of 2020 emissions by the United States, the world's highest per-capita emitter and largest total emitter after China as of 2019. For these reasons, financing climate-friendly innovation in global agricultural practices features prominently on the action agenda of issues to be discussed in Egypt next month at the international Conference of the Parties on climate change.

Solar solutions: Solar jobs are coming to Arizona, and environmentalists, economists and engineers can't wait

Agriculture and climate change are also intertwined in that both influence global migration of (mostly poor) people looking for work, displaced from their homes, or both, as more regions of the world become uninhabitable due to drought, flooding and destructive storms.

As other experts have discussed, a "mass migration of people to Arizona from the coasts" may strain local resources. The rapidly-growing southwestern U.S. is not alone in this problem. And a recent investigation by The Arizona Republic revealed at least one Maricopa County farmer to be tapping into cheap, prisoner labor, raising questions about how far the issue of injustice in climate-strained agricultural work extends.

"Whether it's African folks going to do farm labor in Italy or Eastern Europeans coming into Germany, wherever it might be, there is a connection between migration and our global food systems and abusive labor practices. The same exists in Arizona," said filmmaker Ibañez, who grew up here as part of an immigrant family.

"The racism in Arizona is very aggressive," she said, "and it's very in your face."

While the number of farms and agricultural workers in Arizona is a small fraction of that in California — crop cash receipts in Arizona totaled $2.25 billion in 2021 to California's $38.3 billion — the "Fruits of Labor" film highlights food injustices that may reach every corner of the world as climate-related strains on crop viability, fuel prices and worker conditions limit the availability of nutritious food.

Dealing another New Deal?

In recognition of growing obstacles to growing food, at the end of September the Biden-Harris administration announced an $8 billion commitment to its "transformational vision for ending hunger and reducing diet-related disease by 2030." The release does not mention farm laborers specifically, though it points to the need for intervention in "areas with low food access, such as agricultural communities."

Other aid may come in the form of revisions to the Farm Bill, a modern extension of some of those agricultural provisions laid out by Roosevelt in the 1930s. It is typically revised every five years and due to be renegotiated in 2023.

Read the series: The latest from Joan Meiners at azcentral, a column on climate change that publishes weekly

Some experts anticipate that the extent to which farm labor injustices are addressed in the next Farm Bill may depend on the outcome of the midterm elections. Republicans have signaled intent to cut the bill's allocation to nutrition aid.

A shift in which party controls the House next year may also result in cuts to overall funding for climate adaptation in agriculture. The Inflation Reduction Act, passed in early August, has been hailed by supporters as a historic investment in climate action, with nearly $370 billion allocated to reducing emissions and expanding renewable energy, $18.5 billion of that specifically for developments in "climate-smart agriculture."

If House control flips after the midterms, some of that progress may be negated. In August, Bloomberg reported that GOP agriculture leaders may seek to "skip similar spending" on climate when finalizing the next Farm Bill.

Ibañez was excited to see the IRA incorporate considerations of agriculture and domestic labor. But she worries about related legislation stagnating, such as repeated failures to pass a version of the Child Care Act that would raise the legal age of farm workers from 12 to 16, along with ongoing investments in the climate.

“There’s a major connection to climate change. The increased heat that we’re experiencing has led to higher death, fainting and illness on the job. Growers are growing less so there’s less work for workers, because growers don’t have enough water."

For now, she's raising awareness about food justice by continuing to screen her film at festivals. It also airs periodically on PBS and can be borrowed, along with a discussion guide for teachers, from the PBS lending library to show in K-12 classrooms for free. To check the schedule or find another opportunity to view the full film, visit FruitsofLaborFilm.com.

If you are or know a farm laborer or organizer in Arizona who would be willing to share perspectives on tending or harvesting local crops in a drying, warming climate, please email Joan Meiners at joan.meiners@arizonarepublic.com

Joan Meiners is the Climate News and Storytelling Reporter at The Arizona Republic and azcentral. Before becoming a journalist, she completed a doctorate in Ecology. Follow Joan on Twitter at @beecycles or email her at joan.meiners@arizonarepublic.com.

Support climate coverage and local journalism by subscribing to azcentral.com at this link.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Climate change could raise produce prices, slow food justice fight