Climate change could threaten NC's wild turkey population. Here's how.

After European settlers hunted Eastern wild turkeys to near extinction in previous centuries, Benjamin Franklin's favorite bird has made an amazing recovery thanks to aggressive reintroduction efforts and stringent hunting regulations.

That includes North Carolina, where the introduction of wild birds from other states starting in the 1950s has led to the wild turkey's population growing from just a few thousand birds as recently as the 1970s to an estimated 270,000 across the Tar Heel State today.

But wild turkeys in North Carolina and much of the South could be facing a new obstacle, and like previous challenges, this one is also the result of human actions.

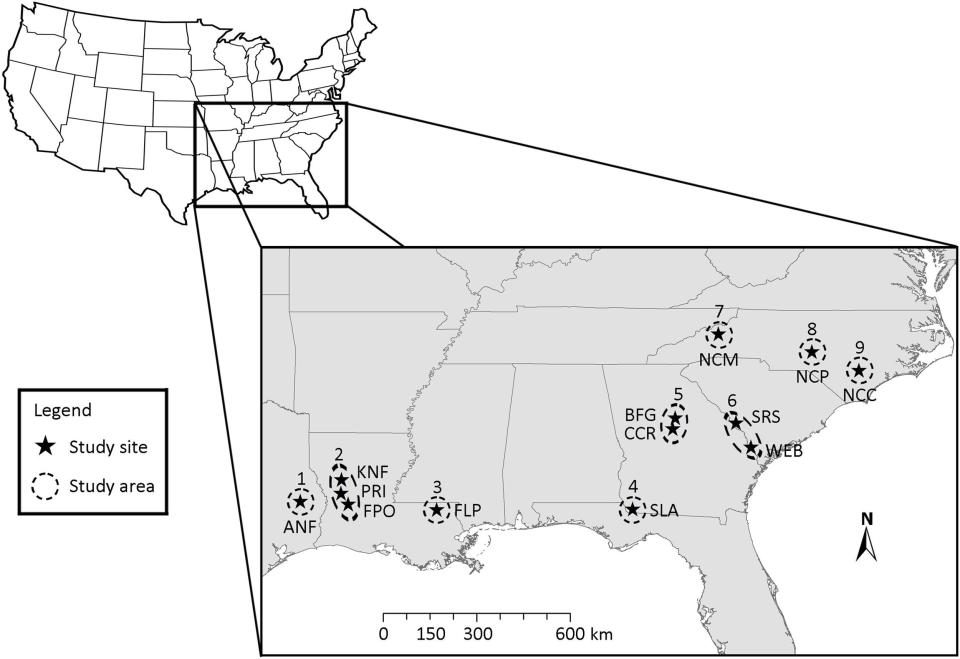

A study in the journal Climate Change Ecology using eight years worth of nesting and weather data from five Southern states found that turkeys might have trouble keeping up with temperature and precipitation changes brought on by climate change.

What they found was that while the weather showed significant variability between January and March, the turkey's nesting response could be measured in days or even just hours − not enough to keep up with climate changes forecast to take place in coming decades.

BITING TIMES Climate change could mean more breeding and biting mosquitoes for Wilmington. Here's why

If wildlife species, such as wild turkey, do not adapt to these weather and climate changes, the timing of their reproductive activities may become mismatched with the timing that maximizes the amount of food available to their young. In short, turkey poults − or chicks − could be born out of sequence as to when the insects and other invertebrates they depend on in the early stages of their life are readily available, and researchers fear this could lead to population declines in a species that's already struggling in many areas.

"There's definitely a mismatch between green-up and when they're reproducing," said Dr. Wesley Boone, lead author on the study and a postdoctoral research scholar at N.C. State University. "And as that period when we see green-up changes, comes sooner, there's a worry that there's going to be more and more of a disconnect."

Warming temperatures are on the way

That a warming planet is stressing birds and other wildlife isn't new. Numerous studies have found that earlier springs are already impact migratory birds and songbirds that summer in Europe and North America.

“Future climate change–associated phenological shifts will likely result in a decrease in breeding productivity for most species, given that bird breeding phenology is failing to keep pace with climate change,” the study states.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) says that temperatures in North Carolina have risen by more than 1 degree since the beginning of the 20th century, and more and likely accelerated warming is projected this century. The U.N.'s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says worldwide temperatures could increase by 3.6 degrees or more above pre-industrial levels if aggressive measures to curb the emission of greenhouse gas emissions aren't implemented quickly in the coming years, something countries aren't on pace to meet.

SLOWING DOWN? Study says climate change could impact the rapid growth along the NC, SC coasts

As temperatures warm, Mother Nature starts spring earlier, and with the shoots of new vegetation come the bugs and other invertebrates to eat them − and a vital food supply for baby turkeys that forage on the forest floor and can't fly.

But many birds nest according to the length of the day, and that's not changing.

“When they’re nesting should stay the same," Boone said. "What we do expect is green-up in the Southeast to come earlier and earlier in coming decades.”

Researchers believe migratory birds might have an easier time of adapting than larger, less mobile birds like turkeys because of their ability to redeploy north to cooler areas that match their internal breeding clock.

"But flying isn't really one of a turkey's strengths," Boone said. "Yes, they can fly. But they're not too good at that."

A cause for concern?

Any change in nesting success could have impacts on wild turkey populations and subsequently the ability of hunters to harvest the popular game bird. Already some states are seeing declines in their wild turkey populations, although the cause or causes has yet to be identified by researchers.

North Carolina Wildlife officials announced in June that the state's five-week wild turkey season yielded 24,089 recorded harvests − the highest total ever recorded here. The previous high was 23,341, set in 2020, with harvest numbers at the coast up 14%.

GOBBLE GOBBLE! North Carolina sets wild turkey harvest record for 2023 seasons

The top five counties for the number of turkeys harvested were Duplin (829), Pender (689), Bladen (652), Sampson (585) and Brunswick (571).

While climate change might bring some long-term concerns to the state's wild turkey flock, the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission says the biggest pressure the birds face − common to other wildlife − is the loss of habitat and a decrease in habitat quality. Officials added that the state's turkey population is considered "stable," and no changes to the spring turkey hunting season are under consideration.

Boone said the recent study shows climate change will have an impact on the turkeys. But what that means long-term, such as the effect on nesting success and chick survival, is still to be determined.

“Are they going to respond to climate change when they reproduce? Probably not," he said. "But is that a cause for concern? We really need more research into that."

Reporter Gareth McGrath can be reached at GMcGrath@Gannett.com or @GarethMcGrathSN on Twitter. This story was produced with financial support from 1Earth Fund and the Prentice Foundation. The USA TODAY Network maintains full editorial control of the work.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Wild turkeys in NC face impacts from climate change