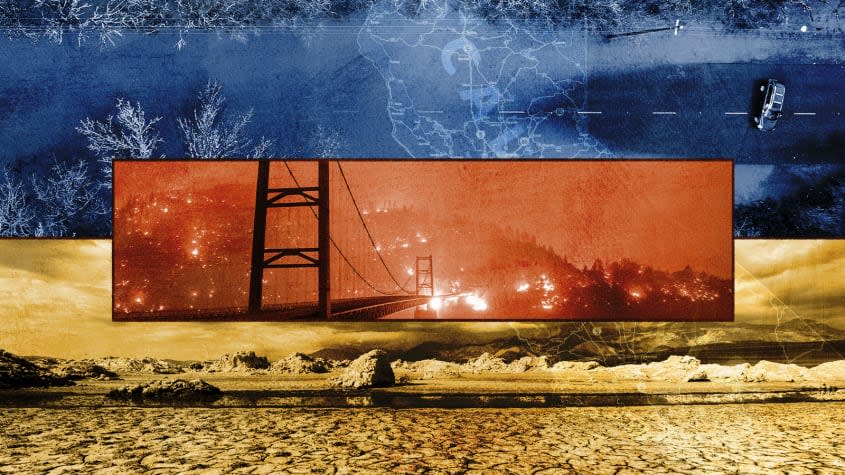

What climate change means for California

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

California is feeling the devastating effects of changing climate. Droughts are becoming more severe and lasting longer, wildfires are burning hotter and spreading faster, and storms that cause severe flooding are becoming more frequent. Here's everything you need to know:

How is climate change affecting California?

The California Natural Resources Agency has put together three climate change assessments which look at what the state is already facing because of climate change and what it can expect. Because about 85 percent of California's population lives and works in coastal counties, there are major concerns about rising sea levels. The assessments found that already, the sea level along California's coasts has risen almost 8 inches in the last century. It's estimated that by 2100, the sea level could rise by as much as 20 to 55 inches; in the worst case scenario, that would put close to 500,000 Californians at risk of flooding, and increase the chance of saltwater contaminating fresh water.

Fires are also a major concern. California has 33 million acres of forest land, and already, climate change is affecting how wildfires are burning. Five of the 10 biggest wildfires in California history happened in 2020, including the August Complex fire, which burned more than 1 million acres. Because of the drought and hotter temperatures, when a fire starts, the trees and brush are drier and go up in flames faster. The fires not only are burning hotter, but the season is starting earlier and lasting longer. "Climate change is creating the perfect conditions for larger, more intense wildfires," Robert Scheller, a professor of forestry and environmental resources at North Carolina State's College of Natural Resources, said. "We're already seeing fires that we didn't expect to see until 2080."

Storms, too, are becoming more extreme thanks to climate change. Warmer air holds more moisture, and "as humans continue burning fossil fuels and heating the atmosphere ... storms in many places, California included, are more likely to be extremely wet and intense," The New York Times' Raymond Zhong writes. The state can expect more "whiplash" weather, as the warmer atmosphere makes both these "extreme and destructive precipitation events" and droughts more frequent, the nonprofit Climate Signals project says.

When huge amounts of water are dumped in a short period of time on already saturated soil, it can cause flooding, mudslides, and infrastructure damage, as well as loss of life — on Jan. 10, California officials said that in the previous two weeks, 17 Californians had died in storm-related incidents.

What about drought?

The Western United States is experiencing a megadrought, now in its 23rd year. In 2022, scientists determined that the region is the driest it has been in at least 1,200 years, and it's believed that 42 percent of the drought can be directly linked to human-caused climate change. "Drought is not just what happened last week or what happened last month," Richard Heim, a meteorologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, told The Wall Street Journal.

More than a third of the country's vegetables and three-quarters of its fruits and nuts are grown in California, and the state's $50 billion agricultural industry is intrinsically connected to the drought. Roughly 80 percent of the state's water is allocated to agriculture, and it will be harder to grow things when there are shortages and the water has to be diverted. Intense storm-related flooding can also wipe out crops.

"Megadroughts and megafloods are going to have serious impacts on agriculture production and on people's livelihoods at the industry scale," Elizabeth Ridder, a geography professor at California State University San Marcos, said. "But also, day to day, the jobs of agricultural workers are going to become riskier in terms of the conditions under which they work."

Is California's snowpack disappearing?

The snowpack in the Sierra Nevada is vital to the state. When the snowpack melts in the spring, the runoff fills reservoirs and provides water for drinking, irrigation, and hydropower. With higher temperatures caused by climate change, more precipitation is falling as rain rather than snow, leading to years with reduced snowpack and not enough runoff to replenish reservoirs. Those higher temperatures can also cause the snowpack to melt sooner and faster, which can lead to flooding.

In December, January, and February, California saw multiple atmospheric river storms, which carry massive amounts of water — both in the form of rain and snow. In February, an even stronger storm system pummeled the state, with blizzard conditions in Southern California mountains and snow falling at elevations that rarely see it. This very wet winter has been a boost — as of March 20, the statewide snowpack is 225 percent of normal for this date, the California Department of Water Resources said, with the Southern Sierra Nevada at 278 percent of normal for this date. Additionally, the U.S. Drought Monitor lifted Los Angeles County from "extreme drought" to "moderate drought," and the Central Valley from "exceptional drought" — the worst classification — to "moderate drought."

"While winter storms have helped the snowpack and reservoirs, groundwater basins are much slower to recover," Jeanine Jones, the interstate resources manager at the California Department of Water Resources, told KTLA. "Many rural areas are still experiencing water supply challenges, especially communities that rely on groundwater supplies, which have been depleted due to prolonged drought. It would take more than a single wet year for groundwater levels to substantially improve statewide."

One thing to keep in mind about California's weather is it has "always been highly variable in terms of precipitation, temperature, size of storms, and wind events," the University of California Los Angeles' Institute of the Environment and Sustainability said. That was apparent in December 2021, when there was a record amount of snow in the Sierra Nevada, followed by the driest January-through-March in the state's recorded history.

Can excess rain be captured for future use?

Unfortunately, it's not that easy. Andrew Fisher, a hydrogeologist and professor at the University of California Santa Cruz, told NPR that the "short answer" is that rain falls "so quickly that we lack the ability to take that water and set it aside quickly enough in a place where we can store it for later." Much of the state's storm water infrastructure is several decades old, and the pipes are not big enough to deal with heavier, more frequent rains. When it comes to rain water, "we do tend to treat stormwater as a nuisance and try to get it off the landscape as quickly as possible," Fisher said, and while some of it is being directed "towards infiltration basins where it can percolate into the ground," much of it will flow to the ocean.

Storm water technology is constantly evolving, though, and California is "planning to do an enormous amount of work with storm water capture and harvesting" over the next several years, David Feldman, director of the University of California Irvine's water institute, told The Washington Post. Harvesting is "a piece of a complex puzzle," he added, and while rain water might not be the best choice for drinking, "that water can be treated to various degrees of reuse, at least in order to, for example, irrigate plants or irrigate landscaping."

The state has committed $8.6 billion to build water resilience, and in February, California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) issued an executive order to accelerate stormwater capture and expand groundwater recharge by at least 500,000 acre-feet in potential capacity.

Will climate change cause California tourism to take a hit?

Tourism is a $145 billion industry in California. The state tourism agency, Visit California, expects that by 2025, tourism will add $157 billion to the economy, but climate change could slow things down.

"Places that are already hot are going to get hotter," Tamma Carleton, assistant professor of economics at the Bren School of Environmental Science and Management at the University of California, Santa Barbara, told the Times in 2021. "Who wants to go wine tasting or hiking if you're baking?" Napa Valley draws visitors who want to see its vineyards and explore its wineries, and on average, the area now experiences four days of extreme heat a year; it's projected that by the end of the century, that number will jump up to 36, the Times reports. Desert cities like Palm Springs, which already have sweltering temperatures in the summer, would also have more extreme heat days year-round.

Rising sea levels are causing coastal erosion, and if beaches aren't safe or are under water, it would keep tourists away. The ski industry is already feeling a hit — in the last three decades, there has been an increase in the number of low-snow years, Geoffrey Schladow, director of the Tahoe Environmental Research Center at University of California Davis, told the Times. If people can't rely on there to be snow, they won't be booking vacations at mountain resorts, which hurts hotels, restaurants, ski resorts, and shops.

What are officials doing?

The state is taking several steps to reduce carbon emissions and transition to clean energy, with Newsom signing into law in September 2022 a bill pushing through measures to ensure California becomes carbon neutral by 2045. This is part of the California Climate Commitment, a $54 billion investment to fight climate change, cut pollution, and support new technologies and clean energy. The goal of the commitment is to reduce state oil consumption by 91 percent, reduce fossil fuel use in buildings and transportation by 92 percent, cut oil refinery pollution by 94 percent, cut air pollution by 60 percent, and create 4 million jobs, while saving California $23 billion by avoiding the damage caused by pollution.

Newsom called this "the most aggressive action on climate our nation has ever seen," but critics have said the state's plans rely on technology that is still being worked out, as well as successfully undertaking several difficult measures, including getting 30 times as many electric vehicles in operation compared to today.

In January of this year, Newsom announced that due to inflation, a rise in interest rates, and stock market volatility, there is a projected $22.5-billion budget deficit in the next fiscal year, and there will be cuts to some climate change programs. This won't hinder progress toward measures like requiring by 2035 that all new cars sold in California are zero-emission, Newsom added, and he's hopeful that federal funding will fill the gap.

Updated March 21, 2023: This piece has been updated throughout to reflect recent developments.

You may also like

Russia's spring Ukraine offensive may be winding down amid heavy troop losses, munitions shortages