Coal Creek history: How Welsh coal miners ended convict leasing and slavery in Tennessee

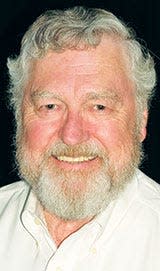

This is a three-part series by Carolyn Krause drawing on Barry Thacker’s “Bringing the Coal Creek History to Life” presentation. Barry made this presentation recently at the Roane State Community College's Oak Ridge Branch Campus. I have known Barry for several years and have found his efforts to preserve the history of Coal Creek to be exemplary. Enjoy learning about this amazing man and his dedication to the local history of Coal Creek.*

In 2000, Knoxville engineer Barry Thacker founded the Coal Creek Watershed Foundation Inc. to improve the quality of life in Briceville and Coal Creek (later named Lake City and now called Rocky Top) in western Anderson County. For years, the foundation has awarded college scholarships to previous students of Briceville Elementary School.

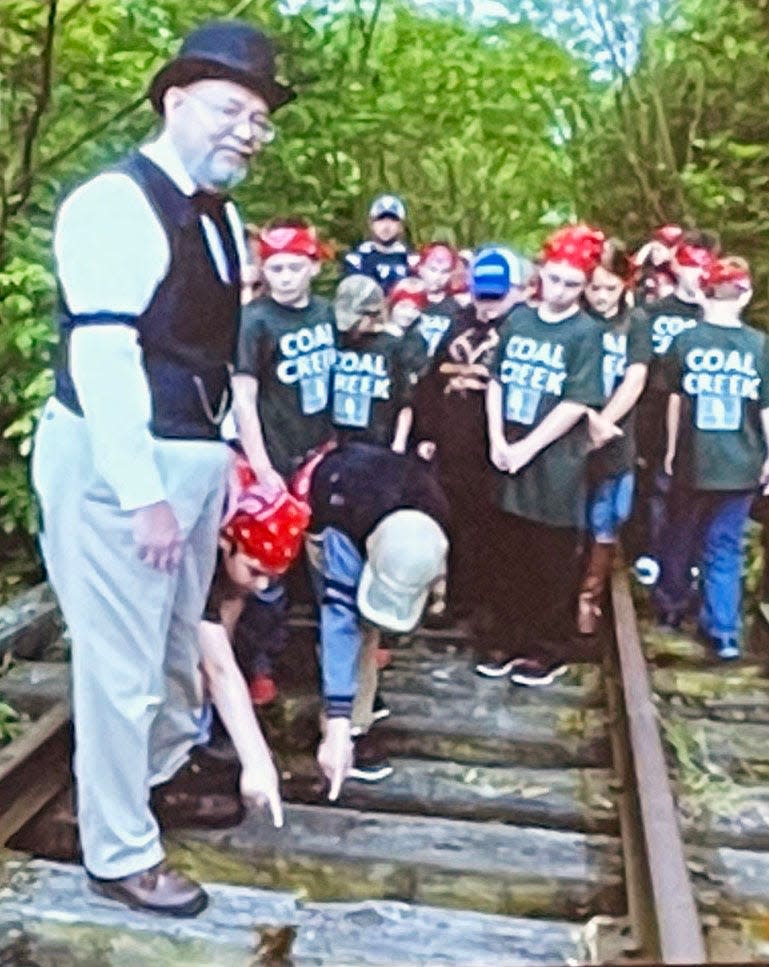

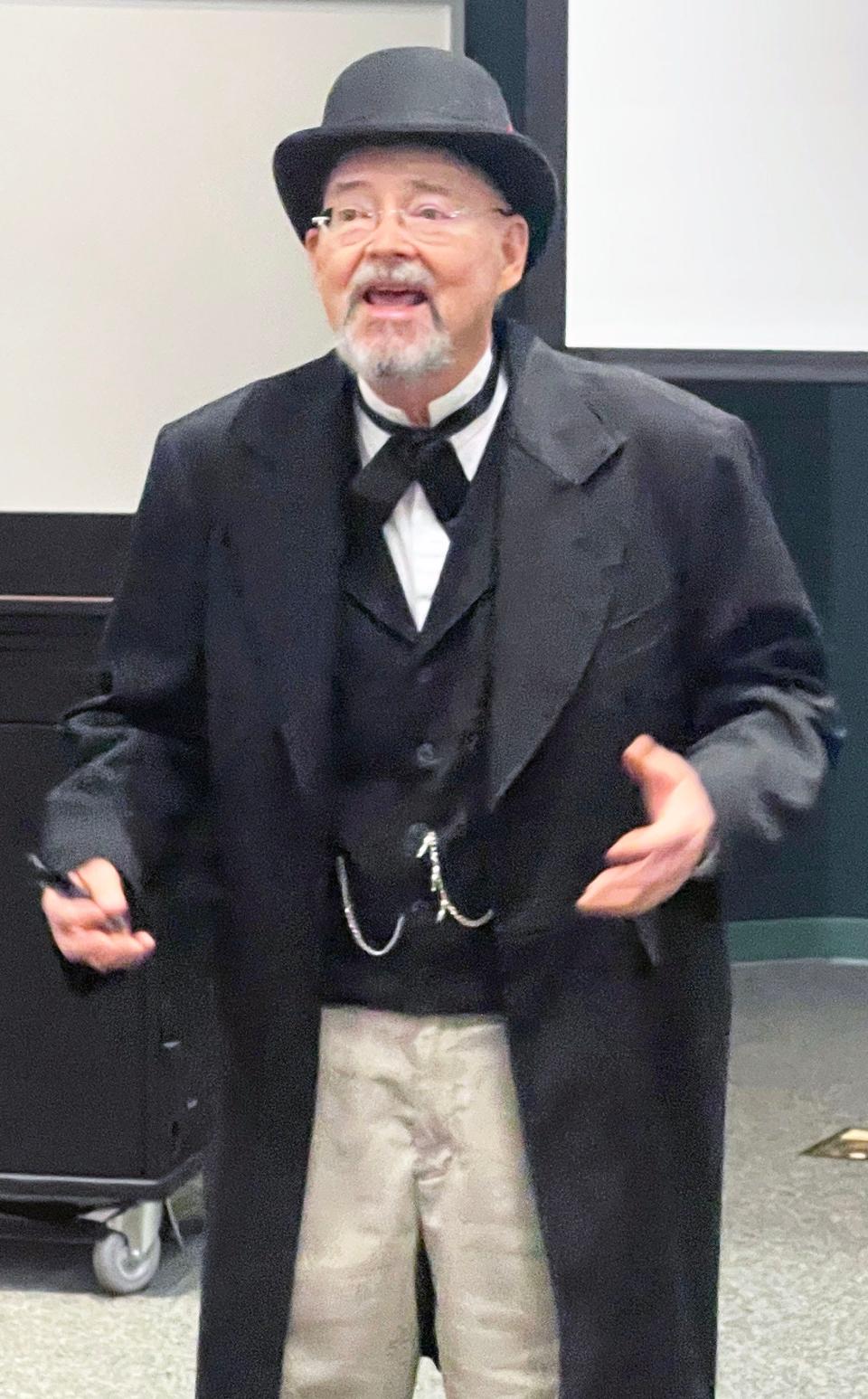

Thacker is also known for his presentations on Coal Creek history in which he portrays David Thomas, a mining engineer of Welsh ancestry who lived in Coal Creek and participated in its history. Thacker has given his talks at the new Coal Creek Miners Museum in Rocky Top and other venues, including Roane State Community College’s Oak Ridge Branch Campus recently.

Krause draws from Thacker’s presentation and other sources to recount the tragic history of coal mining in Anderson County, including the Coal Creek War and mine explosions. According to Thacker, for many young Black male prisoners forced to work in coal mines, slavery in Tennessee didn’t end until 30 years after the 1865 ratification of the slavery-abolishing 13th Amendment, thanks largely to fired Welsh coal miners who helped stop convict leasing.

***

Welsh miners come to Coal Creek

In 1536, Great Britain made it illegal for Welsh people to speak their language and practice their culture and religion. Some Welshmen and their families left Wales for America in the 18th and 19th centuries. At least eight U.S. presidents have Welsh ancestry, including Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, John Adams, Richard Nixon and Barack Obama.

According to Barry Thacker, Welsh miner David Thomas learned about Tennessee from the writings of Samuel Roberts, a prominent Welshman in Great Britain who helped attract Welsh groups to form a Welsh-speaking community with him in Scott County, Tennessee. He wrote about the opportunities for Welsh immigrants in Tennessee, but the community collapsed when the Civil War broke out.

After the war ended in 1865, opportunists in East Tennessee saw that the destroyed region could be rebuilt by taking advantage of the area’s rich natural resources, especially coal and iron ore needed to make steel. Because the Industrial Revolution came to Wales 50 years before it arrived in Tennessee, Welsh immigrants who were highly skilled coal miners and iron workers, unlike native Tennesseans, found they were in great demand in the state and elsewhere.

After Welsh iron masters David Richards and Joseph Richards teamed with businessman Hiram Chamberlain to start the Knoxville Iron and Coal Co. (KICC), David Thomas’s wife received a call at their Ohio home from her uncles, the Richards brothers. They were recruiting Welsh miners and iron workers to move to the Knoxville area and start up the iron production mill in 1868. Black and Welsh mechanics who worked for KICC started the Knoxville neighborhood of Mechanicsville. Thomas and his wife moved to Coal Creek, where he and 100 other Welsh miners opened a coal mine for KICC.

Life was good for nine years for the growing Welsh community in Coal Creek. The Coal Creek Mining and Manufacturing Co. started in the town by William McEwan and Henry Howard Wiley created more jobs. The Welsh people could freely speak their language and practice their religion while building the town’s businesses, roads, houses, schools, and churches.t

Convicts become miners and the Coal Creek War

Unfortunately, in 1877, a recession led to the slashing of area coal miners’ wages, and many miners went into debt or had to buy fewer goods because their prices were rising in company stores. Because the miners supplied coal to businesses and homes for heating in winter, as well as to KICC, they went out on strike. Individual consumers of coal revolted, and the striking miners were fired.

Convicts from Tennessee’s overcrowded prisons replaced striking miners in the mountain mines of the Cumberland Coal Mining Co. in Oliver Springs in 1889. The primary leaseholder of the convicts was the Tennessee Iron, Coal and Railroad Co., the largest employer in Tennessee and one of the few companies listed in the first Dow Jones Industrial Average published in 1896. The smaller companies each paid this company a fee for unskilled convict laborers, who cost much less than the highly skilled Welsh miners. Most of the revenue went to the state.

Many convicts were young Black men arrested for petty crimes in Nashville and Memphis; because they lacked mining skills, dozens of Blacks died in the mines. Southern states got away with making slaves of Black convicts because of the “involuntary servitude” loophole in the 13th Amendment, which outlawed slavery except as punishment for crime.

After he was fired as a miner, Thomas found a better-paying job as an apprentice to an engineer at the highly productive Fraterville mine, which along with the Thistle Switch mine did not use convict labor. Other Welsh miners rose to become mining engineers, mining superintendents and mine owners in Tennessee and other states.

What triggered an armed insurrection by unemployed Welsh miners was the state’s decision in July 1891 to give free convict labor to the Tennessee Coal Mining Co. for its Briceville mine because a penitentiary farm in Nashville had burned down. After a July 14 meeting at the Thistle Switch mine, some 200 miners, armed with rifles, stormed the convict stockade in Briceville, captured the convicts and guards, marched them to the train depot in Fraterville, put them on a train to Knoxville and sent a telegram to Gov. John Price "Buck" Buchanan demanding that convict labor be removed from the mines.

The governor brought soldiers from the Tennessee National Guard, met with the miners and explained that convict leasing was the state’s major source of revenue. He was informed that Black convicts were dying in the mines.

Unsatisfied with the governor’s explanation, the armed miners then captured the convicts, the guards and Tennessee National Guard soldiers at both the Briceville and KICC company mines, marched them to Coal Creek and sent them by train to Knoxville and Nashville, along with another telegram to Gov. Buchanan. He called for a truce while he met with the state legislature. In the meantime, the miners and families of Welsh ancestry traveled to Chattanooga for the annual Dixie Eisteddfod celebration that featured choral, poetry and essay writing, and other competitions.

In the next attack, property was damaged as some miners burned parts of stockades housing convicts. Some convicts escaped, including young Black men and hardened criminals such as Henry Baker, who rode with the Jesse James gang and later robbed a Memphis bank. The prisoner escapes brought the Welsh miners bad publicity, but it got worse when they learned that the state legislature passed a law making it a felony to interfere with convict leasing. Now, the miners knew they could be arrested and returned to the mines as skilled, unpaid slave laborers. Feeling betrayed by the governor and determined to end convict leasing, they captured several hundred convicts from the Briceville, Coal Creek and Oliver Springs stockades and set them free!

The New York Times published a story stating that thousands of convicts had been set loose in the hills of Tennessee. Worried about whether he would be re-elected, Gov. Buchanan sent a much larger contingent of the Tennessee National Guard troops to the Coal Creek area. The soldiers built and occupied Fort Anderson on Militia Hill. They fired their cannons and Gatling guns through Wye Gap into the town of Coal Creek. One day the miners captured the fort’s commander when he was half inebriated in the town. They threatened - by telegram to the governor - to lynch the colonel if the convicts and soldiers were not removed.

The New York Times, Washington Post and Harper’s Weekly all sent war correspondents to Anderson County to cover the Coal Creek War in the summer of 1892 between coal miners and a state militia. Armed only with squirrel rifles, some 2,500 miners from Tennessee and Kentucky were overwhelmed by the soldiers’ firepower and “lost the final battle but won the war,” Thacker said. Because of the unfavorable publicity, Gov. Buchanan was not reelected. The new governor, Peter Turney, had campaigned on a promise to end convict leasing, which resulted in the deaths of 131 convicts. Turney successfully persuaded the state legislature to appropriate funds to build Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary in Morgan County by 1896 next to a coal mine.

In this way, the state could offset the revenue loss from the abolition of convict leasing by selling coal on the open market and coke from the prison’s coke ovens for making steel. The prisoners were trained to mine coal safely to reduce the death rate and increase state revenue, and the mine was operated until 1938.

Miner Dick Drummond's ghost

Thacker likes to tell the true story about a tall, handsome Welsh miner named Dick Drummond, who fought in the Coal Creek War and famously attracted women away from the soldiers with whom they were chatting and dancing.

“Dick Drummond got into a fight with a soldier over a dance in 1892 and later that night that soldier was found shot dead,” Thacker said. Angry soldiers dragged Drummond from a boarding house and lynched him by hanging him from a railroad tie on what is now called the Drummond Bridge, which crosses over Coal Creek in Briceville.

The ghost of Drummond that people have sensed at night at the haunted bridge is believed to be looking for revenge or a girlfriend from the past, Thacker said. He called the ghost “the face of the ending of the presence of militia soldiers in Coal Creek and of convict leasing and slavery in Tennessee.”

***

In the next "Historically Speaking" column, and second in this three-part series, Carolyn Krause continues the Coal Creek history using Barry Thacker’s presentation “Bringing Coal Creek History to Life,” and the Coal Creek area mine explosions in the early 20th century that led to improved mine safety.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: How Welsh coal miners ended convict leasing and slavery in Tennessee