Coastal Georgia nonprofits help to fill gaps in support for teens aging out of foster care

According to National Alliance to End Homelessness, nearly 590,000 people experienced homelessness in 2022, some of whom were young adults who have aged out of the foster care system. With no support system to lean on, many of those former fosters are left to fend for themselves.

The Georgia Department of Human Services does not keep statistics on how many 18 to 21-year-olds are homeless in the state. According to the Fostering Success Act, which was signed by Gov. Brian Kemp in July 2022, 700 young people age out of the foster care system each year in Georgia. The act awards income tax credits to corporate and individual taxpayers who contribute to a Qualified Foster Child Support Organization.

Ellen Brown, deputy director for the Office of Communications at GDHS, said young adults can receive support in various ways to include housing choice vouchers, extended foster care up to 21, education support after high school and more.

“Additionally, the Fostering Success Act has allowed for community organizations to create a broader and more accessible service array for young adults both in and outside of DFCS custody,” said Brown.

But in some Georgia counties, such as Effingham, there is no public housing agency to administer federally supported housing subsidies. So, organizations in Chatham and Effingham counties are coming together to ensure young adults have a safe space to meet their basic needs – and to rebuild their lives.

More: Savannah's venerable Back in the Day Bakery to close doors for good on Valentine's Day

'Glad I am able to do this'

Whitney Gilliard entered the foster care system in Washington, D.C., at 14 when her father passed away. Her mother had left the family years before, when Gilliard still was an infant. At 21, she aged out of foster care, which she describes as similar to someone being released from prison.

“Sometimes they are given a Greyhound ticket to a local homeless shelter, or if they have relatives to go too, they may take a taxi there,” said Gilliard.

“I felt ill-equipped and dumb,” said Gilliard of her own experience. “It's like putting you in a boat in the middle of the sea and telling you to sail, and you know nothing about what's in the water. You don’t know if the water is turbulent. You don't even know what to do if somebody handed you a life saver.”

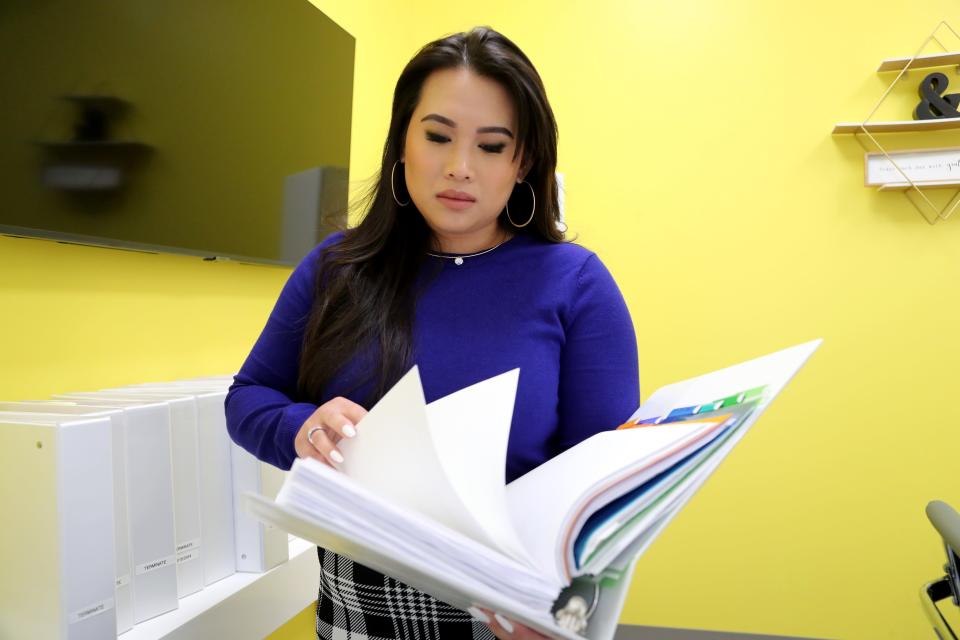

In 2014, she launched Gilliard and Company, a nonprofit that assists 18- to 20-year-olds who have aged out of the foster care system. Gilliard operates an Independent Living Program in Savannah, where young adults go through a program that leads them to independence to become self-sufficient, as well as working alongside staff members to enroll in school or find employment opportunities.

Gilliard and Company is funded through state contracts, which helps the organization pay for social workers and other expenses. The nonprofit also receives funding through donations. Colleges such as Georgia Southern University have helped spread the word to young adults in need. Young people have come to Gilliard and Company from all over the state, including Atlanta, Macon and Thomasville.

Through her ILP, Gilliard has had young adults join the military, get a technical degree and even rekindle the relationship with their parents.

“They are figuring themselves out and learning how to control their circumstances,” said Gilliard.

Per state regulations, a former foster must have a high school diploma, no adult criminal record and pass an assessment in order to qualify for the ILP. The assessment determines whether or not one can complete basic tasks, such as cooking on their own or knowing when to ask for help in certain situations.

Gilliard said it has been a joy watching young adults come through her program. To see them go into the world equipped with the right tools gives her peace and reminds her why serving the community is so essential.

“I’m just glad I am able to do this,” said Gilliard.

More: Savannah prepares to update Historic Landmark District application with more inclusive history

More: Savannah-Chatham public schools to present revised strategic plan to board

'Empty nesters pitching in'

Katrina Bostick, who runs the non-profit housing assistance program Family Promise of the Coastal Empire, became involved with helping place former fosters with empty nesters after she received a call from the Effingham County School District, which alerted her that current and former students were struggling to get a foundation beneath their feet after leaving foster care.

Funded through public and private donations, Family Promise typically works with families who qualify for short-term housing who have children under the age of 18. The organization also links families to mental and health care services, provides resources for financial literacy and more. The empty nester program was created in the “spur of the moment,” she said, as a way to fill "the gap for those young adults during that time."

Empty nesters are vetted through background checks. In addition, various meetups are scheduled to ensure families and their new charge can interact before the individual moves in.

Bostick said they do not have a large-scale recruitment or advertising program that encourages empty nesters to sign up and that it has spread through word of mouth. “We were having different conversations in different spaces, and there were individuals that expressed that they would possibly be interested in hosting young adults until they could connect to some sustainable resources.”

Once a family shows interest in becoming an empty nester, there is a meet-and-greet between the family and the youth.

“Once that plan is devised, then we look at execution as far as who will be responsible for pickup, drop off, for this and that – there are a lot of moving parts,” said Bostick. “But for us, we want to make sure that the host family or the empty nester family is comfortable.”

Family Promise keeps in touch with young adults placed under the care of empty nesters as their health and well-being is top priority.

“We still have communication with them and we are in constant communication with the host house,” said Bostick. “These individuals in our community have been really instrumental in opening their doors, saying that we want to fill a need.”

According to Bostick, empty nesters do not take in whole families and because their guest is an adult, the organization does not “get into the logistics” of the individual's background regarding their family.

“At that point, you can't really force a parent to continue to house an adult in a sense,” said Bostick. “When we know that a young adult has been displaced, our main focus is making sure that we have those resources in place for those young adults.”

'Going to take a community effort'

Bostick is grateful for the way the community has rallied to address young adults experiencing homelessness but stresses that more resources are needed to prevent a cycle of poverty and homelessness that may span generations.

“If we don’t address child homelessness, we will have to address adult homelessness and that is very costly,” said Bostick. “It is going to take a community effort. We need to look at what we can do to help families live a successful life.”

But without a housing authority in Effingham County, the community can only do so much.

“We have great partnerships but the agencies we have alone cannot serve homelessness,” said Bostick.

For those students facing homelessness who are still in school, walking the halls among their peers can be even more stressful if their classmates are aware of their situation.

“If other people know what’s going on, they don’t feel like they have the friends or relationships to help them cope,” said Kathy Megli, a social worker for multiple schools in Effingham County.

If a student is not in school for a certain length of time, they may not qualify for vital learning assistance, such as an Individualized Educational Program. However, the school district uses other resources to ensure students do not fall behind academically.

“There are resource classes for students who qualify due to having significant gaps in learning to bring them up to speed and help them not get further behind,” said Megli. “Retention is always an option, but it is something that we really try not to do, especially when the family is already dealing with hardships. But sometimes it is the best thing that can happen for the student just to have an extra year to grasp concepts well before they move on to additional learning goals and targets.”

Latrice Williams is a general assignment reporter covering Bryan and Effingham County. She can be reached at lwilliams6@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Coastal Georgia nonprofits fill gaps for teens aging out of foster care