A Colorado Senate Race Tests The Appeal Of Progressive Populism

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

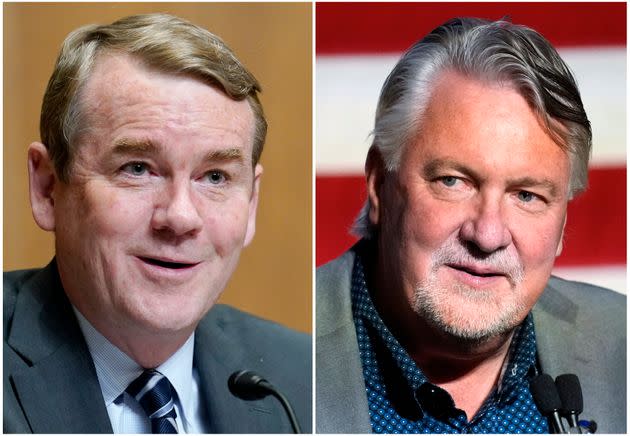

Republican Joe O'Dea, right, is hoping to deprive Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) of a third full term. (Photo: Associated Press)

PUEBLO, Colo. ― It took only a minute for Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) to say the magic words: “trickle-down economics.”

“You remember that trickle-down economics, that supply-side economics, that privileging everybody in our in our economy and in our society that wanted to export stuff and make it as cheaply as possible in China and Southeast Asia?” he asked a few dozen loyal Democrats assembled to hear him speak at a historic railroad station on Sunday. “The result has been that for more than 40 years, the economy, when it’s grown, has worked really well for the top 10% of Americans, but hasn’t really worked for anybody else.”

The speech was a hit with the crowd in Pueblo, a blue-collar steel town where the geopolitical landscape resembles the industrial Midwest perhaps more than anywhere else in Colorado.

At one point, an attendee interjected to ask what Bennet was doing to raise corporate taxes. Bennet proudly replied that he had fought to insert the “alternative minimum tax” provision into the Inflation Reduction Act, ensuring that corporations pay at least 15% of their income in taxes.

But Bennet, who is seeking a third full term in Congress, doesn’t change his message based on the audience. He deployed a similar narrative before a statewide audience in his televised debate with Joe O’Dea, his Republican challenger, the Friday night before.

And in an interview with HuffPost after his speech in Pueblo, Bennet used “neoliberalism” ― an academic term for post-1970s market fundamentalism ― interchangeably with “trickle-down economics,” blaming the phenomenon for creating fertile ground for former President Donald Trump’s rise.

“It’s almost inevitable in human history that if people lose their sense of economic mobility, that’s when somebody shows up and says, ‘I alone can fix it,’” he said, quoting Trump’s infamous line.

Colorado is an increasingly Democratic state. President Joe Biden won it by 13.5 percentage points in 2020, compared with Democrat Hillary Clinton’s victory by just under 5 points four years earlier.

Still, Bennet is something of a break with recent tradition in Centennial State politics.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis (D) and Sen. John Hickenlooper (D-Colo.), himself a former governor, come from a long line of centrist, business-friendly Colorado Democrats embodied by former Sen. Gary Hart (D), a leader of what was known in the 1980s as the “Atari Democrats.” They are about as likely to denounce “trickle-down economics” or offshoring in their stump speeches as the Colorado Rockies are to win a World Series.

A commitment to confronting economic inequality “sets [Bennet] apart” from some other Colorado Democrats, said Scott Wasserman, president of the Bell Policy Center, a Denver-based think tank that advocates for progressive economic policies in Colorado. “For me, at least, that’s refreshing,” he said.

But Bennet’s reelection bid tests the appeal of progressive populism in Colorado, including by embracing domestic policy achievements under Biden that Democratic candidates in other states are loath to discuss.

O’Dea’s efforts to run as a relative moderate on social issues make the race an even clearer referendum on liberal economic ideas.

“He doesn’t have the luxury of an opponent that is a pro-Trump crazy opponent, that is a kind of extreme right-wing, ‘the election is stolen’ candidate,” said Anand Sokhey, a political science professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “Because Bennet cannot easily run against that like some Democrats around the country, he’s pivoting and distinguishing himself on some other things.”

“But I think also if he had that option ― of just saying, ‘This guy supports Trump and you don’t want that and here I am’ ― it would be a way easier message to communicate,” Sokhey added.

Bennet has made his opposition to "trickle-down economics" a core part of his bid. (Photo: Michael Ciaglo/Getty Images)

‘Things I Didn’t Completely Comprehend’

Bennet’s early career suggested that he would follow in the centrist footsteps of his predecessor, former Sen. Ken Salazar (D-Colo.), whom he was tapped to replace when then-President Barack Obama appointed Salazar secretary of the interior in 2009.

Bennet, a Wesleyan and Yale-educated attorney, moved to Colorado in the late 1990s to accept a role as managing director for billionaire Philip Anschutz’s private investment firm. He played a key role in overseeing the consolidation of three bankrupt movie theater chains into the massive Regal Entertainment Group.

Bennet went on to serve as then-Denver Mayor Hickenlooper’s chief of staff and superintendent of Denver’s public schools. In 2009, then-Colorado Gov. Bill Ritter (D) appointed Bennet, a political newcomer, to serve in the Senate.

In keeping with the fiscal austerity craze in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis ― and perhaps his own centrist inclinations ― Bennet made debt reduction a priority during his first year in office. At a time when housing advocates were desperate for the Obama administration to use more of the Wall Street bailout money to help struggling homeowners, Bennet passed a budget amendment reducing the size of the financial industry bailout and requiring the federal government to use any unused funds to pay down the national debt.

Bennet touted the “pay it back” plan in a TV ad during his 2010 run for a full Senate term.

Another 2010 TV spot, “Common Sense,” also reflected Bennet’s efforts to appeal to business-friendly moderates in Colorado.

“Michael Bennet’s a businessman who saved jobs,” the narrator says. “In his year in the Senate, he’s fought for tax cuts for the middle class and helped pass tax cuts for small businesses so they can create jobs.”

Bennet’s campaign website in 2010 even included a section on “entitlement reform,” a term often used by conservatives for making changes to Social Security and Medicare. Referring to those two programs, Bennet wrote, “We must find a way to preserve the integrity of these programs while reducing the increasingly large impact they have on the overall federal budget.” (More recently, Bennet has said that he wants to increase Social Security benefits for the most vulnerable, and sees lifting the cap on income subject to payroll taxes, among other revenue increases, as the best route for closing Social Security’s funding gap.)

Bennet shakes hands with O'Dea at the conclusion of a televised debate on Oct. 28. O'Dea asked Bennet if he regretted voting for any spending bills in the past two years. (Photo: David Zalubowski/Associated Press)

As Bennet’s Senate career progressed, he began championing more ambitious and traditionally liberal bills.

In 2019, he introduced what would become his signature policy proposal: expanding the Child Tax Credit for low- and middle-income families with an eye toward eradicating childhood poverty. The American Family Act, which sought to increase federal payments per child by hundreds of dollars a month, became the basis for a key component of Biden’s American Rescue Plan Act.

Unlike most other Democrats, Bennet has made the expanded Child Tax Credit, which cut childhood poverty nearly in half, a central part of his pitch to voters. The benefit’s expiration after six months is just another reason to send him back to the Senate to make the tax cut permanent, Bennet argues.

Bennet told HuffPost he is open to compromise with Republicans to achieve his goal, but emphasized that he sees the credit’s “full refundability” ― meaning that it can give a person more cash back than they have paid in taxes ― as essential. For low-income families that already have a negative federal income tax burden, the current expanded tax credit simply amounts to an increase in their incomes.

“It is just inexcusable that the poorest kids in America wouldn’t have the full benefit of the credit,” he said.

Notwithstanding a greater focus on economic inequality in recent years, Bennet has never veered into the most progressive corner of the Senate Democratic Caucus.

For example, rather than get behind Medicare for All, he introduced legislation in 2019 to create “Medicare X,” which would be a public health insurance option that people could buy on the Affordable Care Act exchanges.

In fact, Bennet developed a reputation as something of a gladiator against the left wing of the party during his short-lived presidential run in the 2020 election cycle. He used his limited campaign funds to attack Medicare for All, Sanders’ signature policy, in TV ads, ripping it for requiring Americans to drop their current insurance and enroll in a newly expanded federal program.

“The truth is a health care plan that starts by kicking people off of their coverage makes no sense. We all know it,” he said in one spot. “Before we go and blow up everything, let’s try this: Give families a choice ― keep your health care or join a public option.”

What I have learned during the time that I was in the Senate is that we have the worst income inequality that we’ve had since the 1920s.Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.)

Bennet took some flak from Colorado progressives for his decision to not only oppose Medicare for All, but make opposition to it a core theme of his presidential campaign. Some of those critics confronted him in person during town halls in 2019.

“The themes that he campaigned on were awful,” said David Sirota, a Denver-based progressive journalist who worked on Sanders’ 2020 presidential campaign.

Sirota called Bennet’s focus on attacking Medicare for All “very discordant from somebody who says, ‘I care about economic inequality.’”

Bennet stands by his decision to run those ads. He said it was precisely his focus on reducing poverty and economic inequality that motivated him to run for president ― and limited his patience for what he sees as the wrong kinds of solutions.

“I have not changed. I still don’t think Medicare for All is a good idea. I don’t think it’s a good substantive idea. I don’t think politically it’s a good idea,” he told HuffPost. “I think reversing the Trump tax cuts for the wealthy and having a permanent child tax credit and an enhanced Earned Income Tax Credit, having the alternative corporate minimum tax ― those are really good substantively and really good politically.”

But Bennet admits that hearing the stories of working families struggling to make ends meet ― first as superintendent of Denver public schools, and later, as a U.S. senator ― has made him more empathetic to their needs than he was while working in the private sector.

“What I have learned during the time that I was in the Senate is that we have the worst income inequality that we’ve had since the 1920s,” he said, before rattling off a series of economic criteria on which the United States ranks poorly among developed nations. “Those are things I didn’t completely comprehend.”

Nowadays, even Sirota gives him credit for running unabashedly on progressive economic policies like the expanded child tax credit.

“He understands the salience of economic issues, which is more than you can say of most Democratic senators,” Sirota said.

Joe O'Dea appears on NBC's Meet the Press on Sept. 18 as an image of Trump looms. O'Dea, who is walking a careful ideological line, does not want Trump to run again. (Photo: William B. Plowman/NBC/Getty Images)

A Republican Joe Manchin?

Most outside experts do not see O’Dea’s campaign to unseat Bennet as especially competitive.

Bennet has maintained consistent polling leads over O’Dea, including a 14-percentage-point edge among likely voters in a recent University of Colorado, Boulder, poll.

Perhaps as a result, donors have been warier of investing in O’Dea. As of late October, Bennet outspent him by a more than 2-to-1 margin.

The super PAC gap is equally great, with Bennet getting outside support worth about $19 million, compared to just over $9 million for O’Dea. Tellingly, the Senate Leadership Fund, the super PAC affiliated with Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), has stayed out of the race.

“I will be surprised if [Bennet] falls short,” Sokhey, the University of Colorado political scientist, said.

But unlike many of the statewide Republican candidates expected to lose in an otherwise strong cycle for the GOP, O’Dea’s underdog status is not due to any glaring flaws he has as a candidate.

With the mantra that he is a “carpenter and a contractor” rather than a “politician,” O’Dea has tried to make the election a referendum on Biden, whose approval numbers are underwater in Colorado, and on inflation, which he says the Bennet-backed spending legislation has fueled.

Bennet “dumped $1.9 trillion into our economy that’s caused record inflation,” O’Dea said in an Oct. 28 debate at the Colorado State University campus in Fort Collins. “Compound that with a war on energy fully backed by Michael Bennet and Joe Biden that’s caused record inflation on gas and diesel prices directly reflected in the fertilizer price.”

He also asked Bennet if he regrets voting for any of Biden’s spending bills. Bennet replied that he regrets the inflation people are experiencing, but cast blame for it on “broken supply chains” and oil company price gouging, rather than big spending bills. (Bennet supports legislation that would impose a “windfall profits tax” on large oil companies and invited O’Dea to do the same.)

O’Dea even managed to turn an exchange about Trump into an opportunity to rip Biden. When Bennet asked him why, after voting for Trump twice, O’Dea has said that he doesn’t want the former president to run again, O’Dea implied that Trump’s candidacy would get in the way of defeating Democrats like Biden and Bennet.

“I started thinking about Joe Biden serving another four years, and you serving another six years and I gotta tell you: It’s terrifying,” O’Dea said.

At least one swing voter with whom HuffPost spoke found O’Dea’s anti-inflation message compelling. Fred Lewis, a retired federal employee and registered Republican from Greenwood Village, said he voted for Biden in 2020 because he found Trump “scary.”

Now he’s voting for O’Dea. “I’m tired of what the Democrats are doing here,” Lewis said. “They’re spending too much money.”

Indeed, to many Colorado Republicans, a business-minded conservative like O’Dea is exactly the kind of person who can appeal to moderate Democrats and independents in a highly-educated state where Trump was unpopular.

Dr. John Sacha, a Denver spinal surgeon who had come to hear O’Dea and former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie (R) speak at an alpine-themed bar on Oct. 29, believes that O’Dea’s relative leniency on issues like abortion is a good fit for Colorado Republicans.

“We’re liberal Republicans,” he said. “We’re more middle of the road on social issues, but we’re far right when it comes to everything fiscal.”

To appeal to those voters, O’Dea supports codifying same-sex marriage in law and said he would back federal legislation codifying abortion rights up to 20 weeks of pregnancy, with exceptions for rape, incest, and the life of the mother after that cutoff point. He also said he would have voted for the bipartisan infrastructure bill and wants to give Dreamers ― undocumented immigrants who arrived in the U.S. as children ― legal status, albeit only as part of a comprehensive bill that improves border security.

I’m going to use my seat like Joe Manchin has used his seat to get good things for West Virginia.Joe O'Dea, Republican Senate nominee for Colorado

Rather than Trump or a member of the Republican GOP Conference, O’Dea cites Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) as a model for the kind of independence he plans to embody as a senator.

“When I’m in the U.S. Senate, I’m going to use my seat,” he said at the Oct. 28 debate. “I’m going to use my seat like Joe Manchin has used his seat to get good things for West Virginia.”

O’Dea has to strike a difficult balance between attracting moderates and keeping his conservative base happy. Bennet continues to attack him as an out-of-step radical, citing O’Dea’s opposition to the bipartisan gun control legislation Congress adopted this year, his 2020 vote for a failed state-level referendum banning abortion after 22 weeks without exceptions for rape and incest, and his support for additional tax cuts for the rich.

At the same time, social conservatives are hardly enthusiastic about going to the polls for O’Dea.

Curt Clifton, a retired engineer from Aurora who was wearing a Trump hat, said he did “not particularly” like O’Dea, “but I don’t like the Democrat a whole lot worse.”

His wife, Cathy, a retired nurse and anti-abortion activist, is also going to hold her nose while voting for O’Dea. “I don’t really know if he’s against abortion at the last minute ― at 38 weeks or 40 weeks or something,” she said.

Another factor working in Bennet’s favor is the presence of Brian Peotter, a Libertarian Party candidate, on the Senate ballot. O’Dea clearly sees Peotter as a greater threat to his share of the vote than to Bennet’s.

“The bottom line is: a vote for the Libertarian is a vote for Michael Bennet,” O’Dea told HuffPost after his event with Christie. “And I know all those libertarians, none of them have anything in common with Michael Bennet.”

In part due to third-party candidates, Bennet has never received more than 50% of the vote.

But whether those candidates, who have included left-leaning Green Party nominees in the past, have hurt Bennet more than his opponents is unclear. In 2016, the Libertarian nominee received 3.6% of the vote ― not enough to cover the gap between Bennet and his Republican opponent even if all of them had voted Republican instead.

In reality, O’Dea’s biggest obstacle is the same partisan polarization affecting Democrats in increasingly red states. It’s the kind of political force of nature that makes it unlikely that Rep. Tim Ryan (D) will win in Ohio’s Senate race, or that Rep. Val Demings (D) will win in Florida’s Senate race, despite their strengths as candidates.

When a state’s tribal identity shifts in a more decisive partisan direction, it becomes harder for voters to see any candidate outside of that lens ― especially in congressional races.

“Is [O’Dea] actually going to be able to get much of the crossover vote?” Sokhey said. “Probably not, in the era of polarization that we’re in.”

On the other hand, if O’Dea prevails against the odds, he is likely to be held up as a model for GOP success in similarly difficult terrain. His victory would also speak to the extent of the political backlash to inflation and its perceived link to Biden’s policies.

“If Bennet loses, it’s a very bad night for the Democrats nationally, and it’s probably a bad night for them in Colorado in some other dimensions too,” Sokhey said.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.