Columbus AIDS activist Steve Shellabarger still fighting 43 years after epidemic began

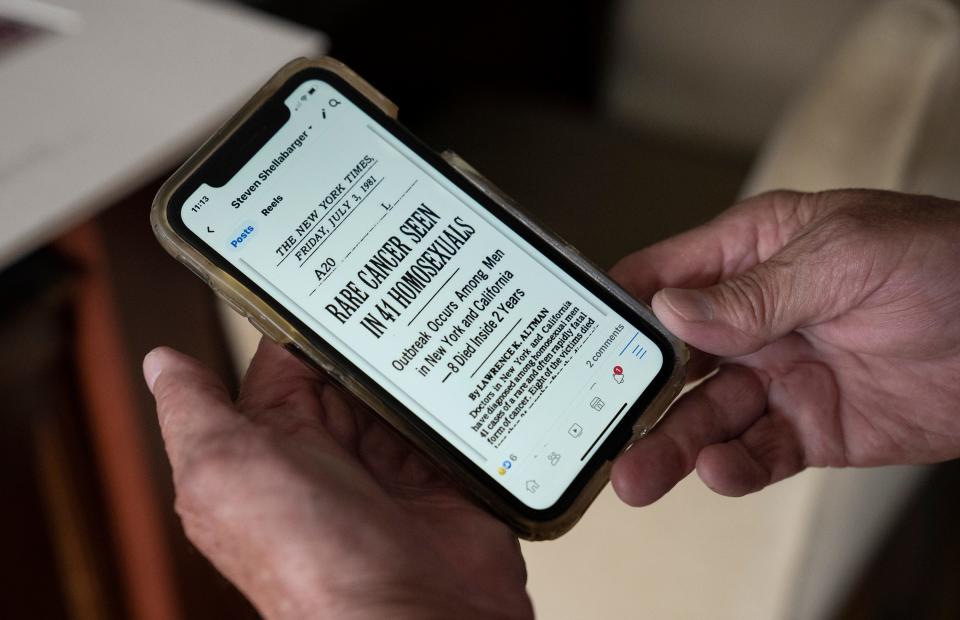

Steve Shellabarger picked up his copy of The Dispatch and flipped to obituaries, scanning the list of names and pictures for his friends, looking to see who was the latest casualty to AIDS.

He, along with other gay men around Columbus, repeated the morbid routine every day during the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the mid-1980s.

"We were burying our friends, and no one knew when they would get it next," Shellabarger said. "I got up every morning and wondered if this was my day."

Read More: HIV is still increasing among Black Americans: These 2 Ohioans are trying to change that

By 1987, Franklin County had the highest per-capita rate of AIDS of any urban Ohio county, according to The Dispatch that December. Franklin County's 100th case of AIDS had just been reported, nearly five years after its first known case in Ohio. Forty of those 100 people had died.

But in the early 1980s, as AIDS cases arrived in Ohio, Columbus had felt like a quiet, safe city to live as a not-yet-out gay man, Shellabarger said. He was in his late 30s and taught high school social studies in Whitehall. He was living in German Village with his partner, Steven Marquis.

Friends eventually got infected. Then they started to die.

"That's when the fear set in," he said. "Some hid, some organized."

Everything, he said, became a group effort to support the gay community. Shellabarger said it was a wake-up call — "like a tap on the shoulder" — to become an activist.

That toe-dip into activism would lead Shellabarger, now 78, to a 40-year career in advocacy work for the LGBTQ community. Since 1983, Shellabarger has worked with the Human Rights Campaign, the Columbus AIDS Task Force (now Equitas Health), Stonewall Columbus and the Legacy Fund of the Columbus Foundation.

"Every organization (Shellabarger) has served is now better off because of him," The Legacy Fund said of Shellabarger in 2016 honoring his lifetime of service.

But in the early days of the AIDS epidemic, Shellabarger was clandestine about his activism.

HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, had already been infecting and killing gay men across the United States since at least 1981. Rhetoric from crusaders like Florida singer Anita Bryant had mounted a growing anti-gay culture war. Ohio lawmakers enshrined stigma into law, like making it a felony for someone with HIV to spit in public, an act that cannot transfer the virus to another (Some of those laws are still on the books today).

Shellabarger had received a letter from the Human Rights Campaign Fund, which at the time was the only national LGBTQ political organization, asking him to start a Columbus chapter.

“I was still teaching school. It was a different time," he said.

Still, Shellabarger said yes. The first fundraiser the Human Rights Campaign held in Columbus was at a party house with paper plastered over the windows. Lawyers waited in the parking lot in case the police or protesters showed up.

"If we were ever going to make change, it had to be the traditional way: raising money and electing politicians," Shellabarger said. "In 1983, we didn't have any allies from any party. That began to change with AIDS."

In 1987, Shellabarger and others realized they needed to take their activism to the next level and start educating their own.

Doctors and health officials were doing what they could to update the public about AIDS, but misinformation was still rampant.

A survey published by the Ohio Department of Health in December 1987 found that many Ohioans held "erroneous beliefs" about how AIDS is transmitted, according to an article by The Dispatch at the time.

A third of Ohioans believed that AIDS could be transmitted by sharing a drinking glass with an infected person. About 19% believed eating in a restaurant where someone with AIDS works put them at risk of infection, and 16% believed AIDS could be transmitted from toilet seats.

People needed facts, Shellabarger said.

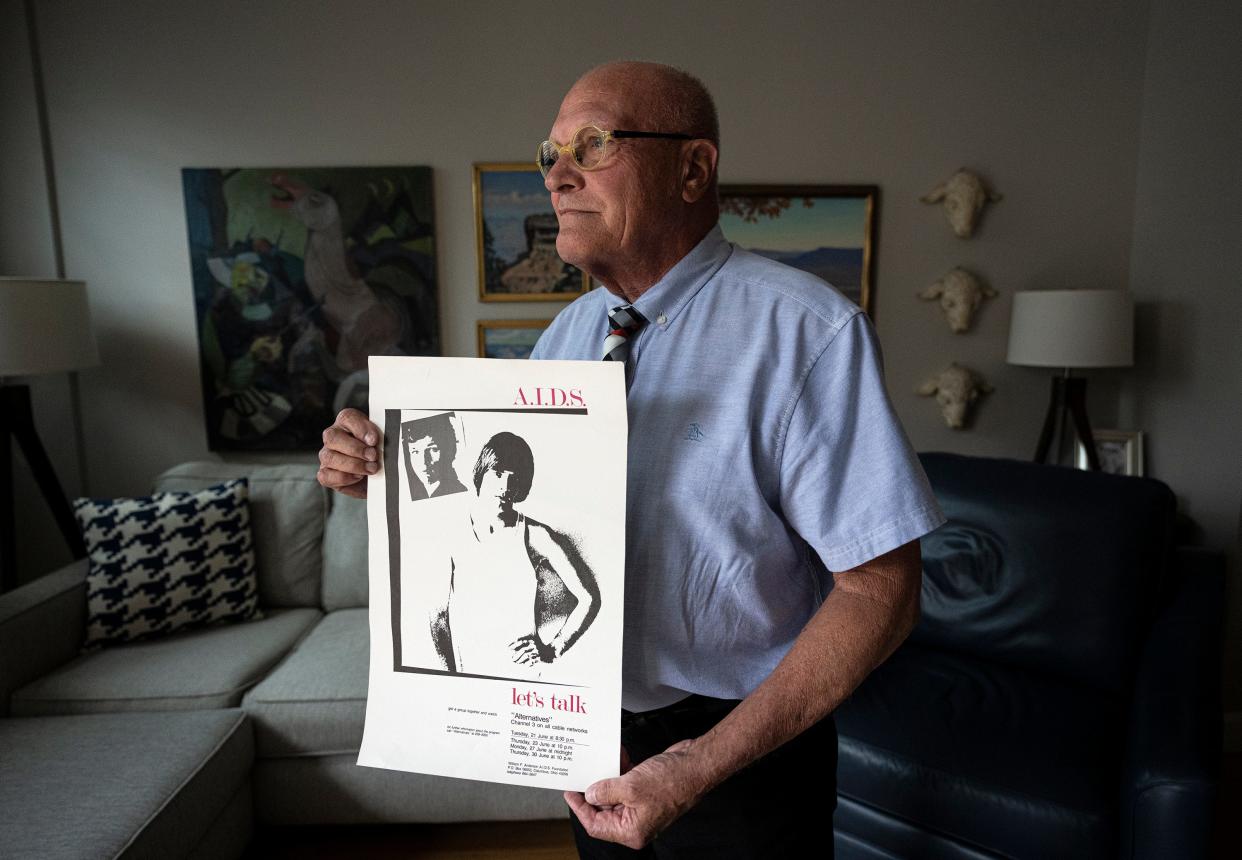

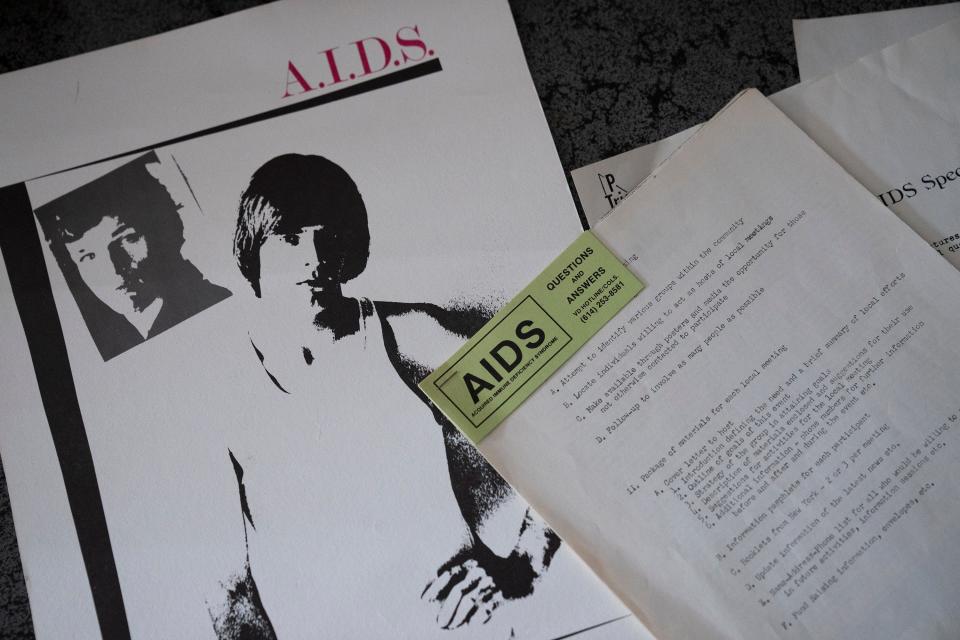

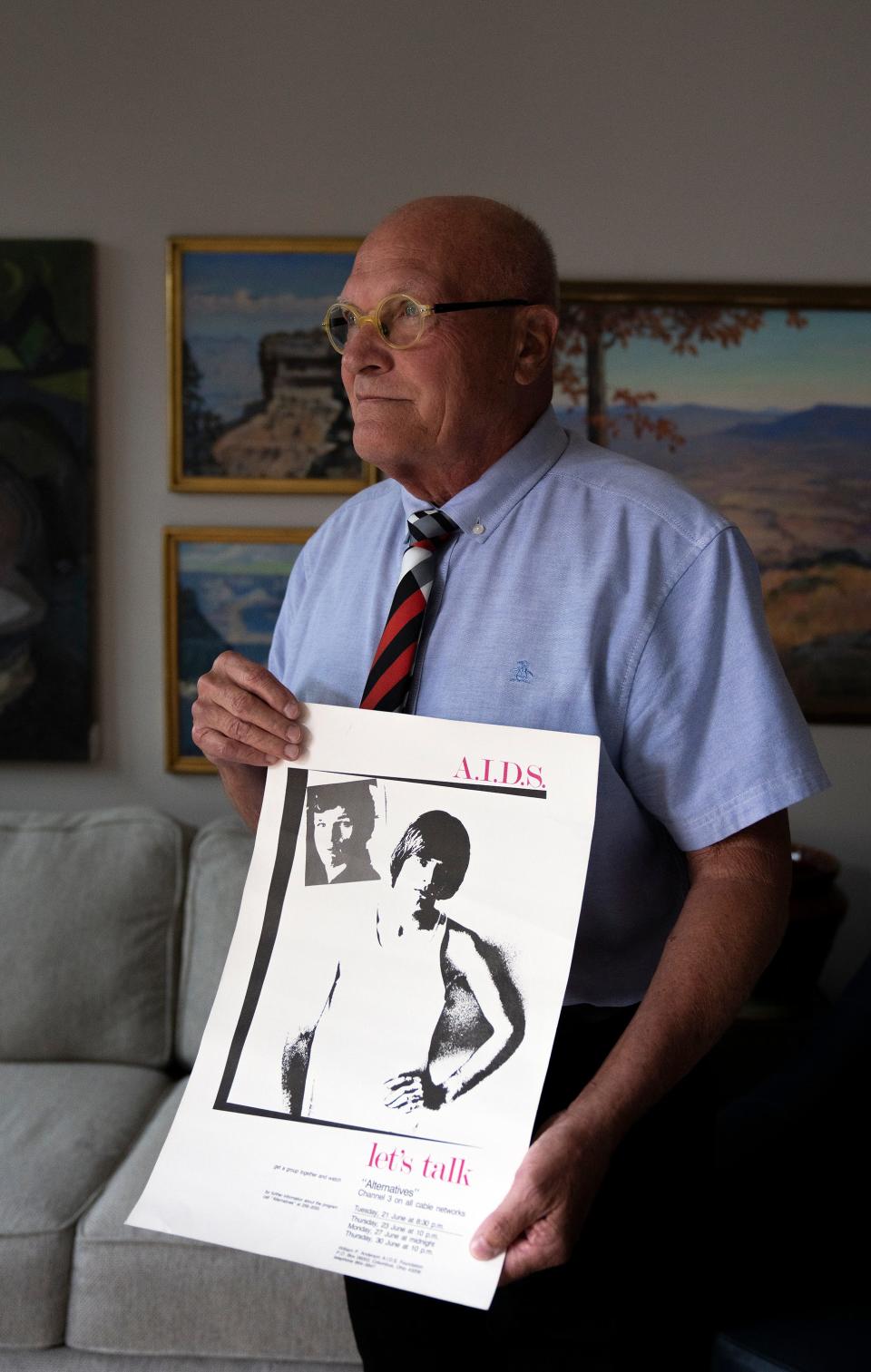

Shellabarger and other activists put together a public access TV program called "Let's Talk," which aired four times in June 1988. They interviewed Dr. Mark Bechtel, a Columbus dermatologist who was one of the first to recognize Kaposi’s sarcoma, now known as "an AIDS-defining illness."

Their group raised money to advertise the program. They printed posters and hung them up in bars around Columbus, telling people to get a group and watch together.

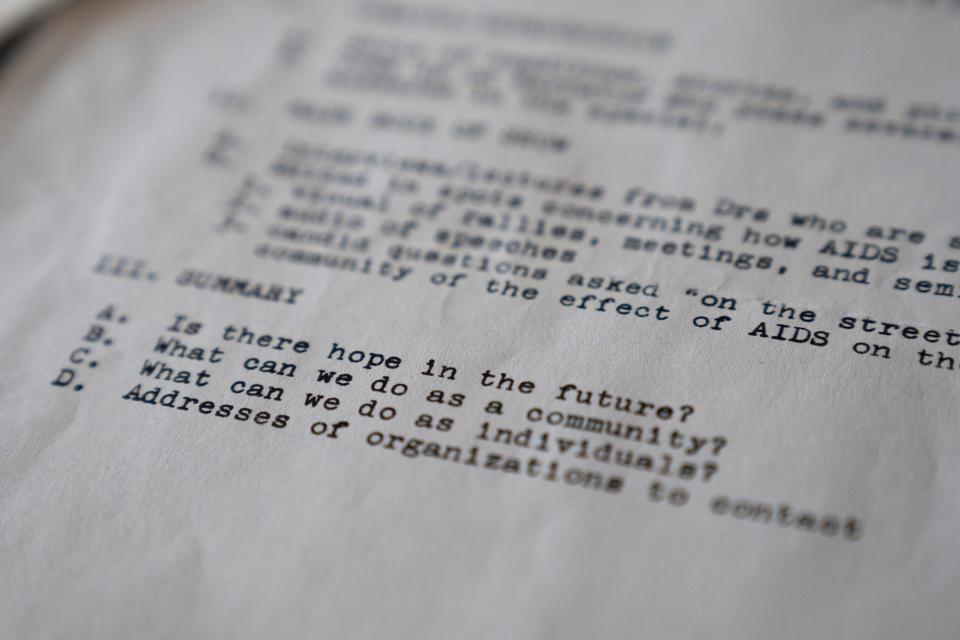

The program was as much about inspiring hope as it was about informing people about AIDS. An outline of the show's talking points ended with three questions: Is there hope in the future? What can we do as a community? What can we do as individuals?

Those questions, in many ways, have guided Shellabarger's lifetime of service to his city and his community. He eventually quit teaching after 20 years to dedicate himself full-time to activism.

"I just knew I couldn't teach and do what I wanted to do," Shellabarger said.

There is a paradox, some experts say, in how the AIDS epidemic ignited an era of activism. At a time when fear and stigma shrouded many gay men in secrecy, Shellabarger said there was also greater recognition, visibility and legitimacy of the LGBTQ community and its causes.

Organizations founded during the AIDS epidemic, including the Humans Rights Campaign and the Columbus AIDS Task Force, spurred decades of LGBTQ rights activism around issues like health care, marriage equality and anti-discrimination laws in Columbus and beyond.

"The closet door was forced open," Shellabarger said. "Without AIDS, gay rights would be nowhere close to where we are."

But advancement didn't come without its scars.

An entire generation of gay men — whom Shellabarger calls "the martyrs" — was lost to AIDS. Among those martyrs were many of his friends and two partners, including Marquis, who died in 1990 from complications of AIDS.

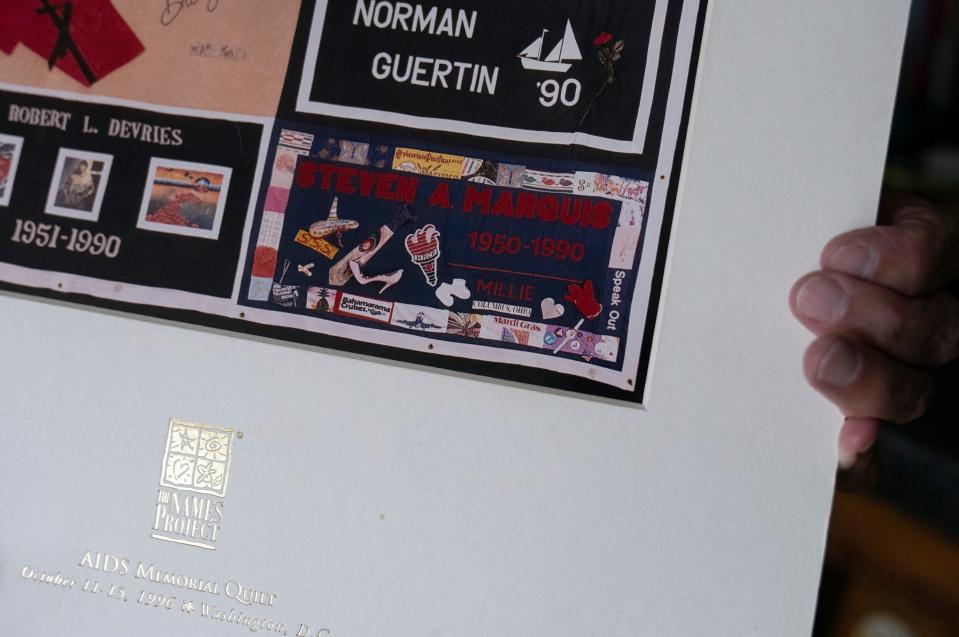

Marquis is memorialized on a panel of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, the border of his panel made up of a patchwork of T-shirts from his and Shellabarger's many travels.

While Shellabarger recognizes how far the LGBTQ community has come in the last four decades, he worries for the future.

He looks across the country and sees bills and laws aimed at "pushing us gay people back in the closet," he said. He sees people who are afraid of what they don't understand. And, worst of all, he said, he sees complacency.

It's a situation that Shellabarger said needs a new generation of activists to take up the call.

"It's not over, and you better be ready to fight," he said.

shendrix@dispatch.com

@sheridan120

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Columbus AIDS activist still fights for change 43 years into epidemic