Columbus farmer inspires locals to take control of their food, build healthy community

Most of us are several steps removed from how our food is made.

A local woman is working to change that in Columbus, inspiring people to grow their own food in an effort to combat poor nutrition and climate change.

Abike Alexendar, founder of Durty Beets, used her second City Farm Feast at Heritage Art Center in Columbus Saturday to inspire community members to grow their own food.

“It’s always a good thing for people to know that they can govern [their food],” Alexander said to her nearly 40 guests during the first of four courses.

Alexander was expanding on her definition of “food sovereignty,” a term that describes burgeoning efforts to combat food insecurity, injustices and poor diet.

The ornately decorated tables were lined with candles, plants and menus.The entire dinner was plant-based and “local”—all grown within 180 miles of Columbus (with the exception of the endives for the salad).

As guests dipped focaccia in spicy olive oil and Alexander’s luscious and creamy home-made beet hummus, murmurs of approval rippled through the room.

The goals of the event were to connect with your community, try plant-based dishes, eat locally, and become inspired to start growing your own food. And an added bonus, leave stuffed.

“I created City Farm Feast so people can enjoy plant-based food in a fun atmosphere,” Alexander told the Ledger-Enquirer. “I want people to get used to eating a more nutritionally based meal that is plant-based.”

Chronic health issues and inaccessibility to healthy food are connected to poor diet; and growing one’s own food gives back power and choice. In the U.S. it’s common for gas station groceries and fast food restaurants to be the only accessible food options, especially in low-income communities that were redlined decades ago.

“A lot of gas stations sell empty calorie food that don’t have nutritional value,” Alexander said.

She calls these areas “food swamps”.

Alexander believes the best way to combat food swamps is through backyard gardening. She envisions a future where Columbus residents grow their own food, creating “micro farms” to trade produce among neighbors, and bring to farmers markets. Then they can start circulating on a macro level.

“You have more control in a small area, you can get more out of it,” Alexander said.

Brad Barnes and Jenn Collins started their backyard garden and expanded to a .15-acre farm in an abandoned lot in Midtown Columbus. Barnes and Collins spoke at the dinner between the second and third course.

“We need more farms,” Collins told the guests. “Be thoughtful about what is already growing in your community and work together. If Keith Sims at Mercy Med is growing butternut squash, grow something else.”

Barnes and Collins act independent of grocery stores as they eat everything they grow, and then sell or trade what is left within the community.

“You can do this in your own backyard,” Barnes said. “This is a part-time job for us.”

Collin’s and Barnes farm, Dew Point, was awarded City Farm of the Year by Alexander.

Jennifer Shawa, Feeding the Valley’s head of fundraising, spoke about the importance of food not just sustaining but nourishing.

“We’re moving from a place of going from a meal being a meal to a meal being medicine,” Shawa said. “Feeding the Valley is in 18 counties to feed more than 135,000 people who are food insecure. The biggest issue [society] has is food waste. Feeding the Valley rescues food from retailers, manufacturers, and farmers.”

Farmers are the most likely to have nutrient-dense food for people who are hungry.

“We’re working hard to increase connections with farmers,” Shawa said. “If farmers have an excess of a product that they are going to throw in compost, we want it to feed the food insecure.”

Keepin’ it Local

Before the endive salad, the guests were surprised by an off-menu offering (amuse bouche) from the kitchen; tomato gazpacho topped with vegan basil pesto and gluten-free vegan croutons. Delectable and smooth.

“The tomatoes in the amuse bouche came from Fitzgerald Farm, in Meriwether, Georgia,” Lauren Havican, the evenings’ chef and chef at the Food Mill told the L-E.

Fitzgerald is about 122 miles away from Columbus, still considered local in Havican’s definition.

The apples in the endive salad came from Ellajay with a radius of 118 miles. The pecans were from Pecan Points in Hartsboro, Alabama, just 33 miles away.

The main course of polenta, butternut squash arrived with a side of bell peppers and shitake mushrooms. The creamy polenta came from McEwen and Sons in Wilsonville, Alabama, near Birmingham, 116 miles from Columbus. The butternut squash and peppers came from Columbus’ very own Mercy Med farms in Bibb City.

Shopping from small, local farms instead of industrialized agriculture can have a healthier impact on the environment and support the macro farms that Alexander sees as success.

“Industrial farms are becoming more and more unsustainable,” Alexander said. “They use more water, more fertilizers, adding pollution that runs off into fresh waters. This is where we see major E. coli outbreaks come from.”

The biggest query of the evening was how shortbread cookie topped with orange slices covered in chocolate was vegan. Chef Havican revealed the recipe with the L-E: “It’s just four ingredients: vegan butter, flour, powdered sugar, and vanilla.”

Plant-based and the Climate Connection

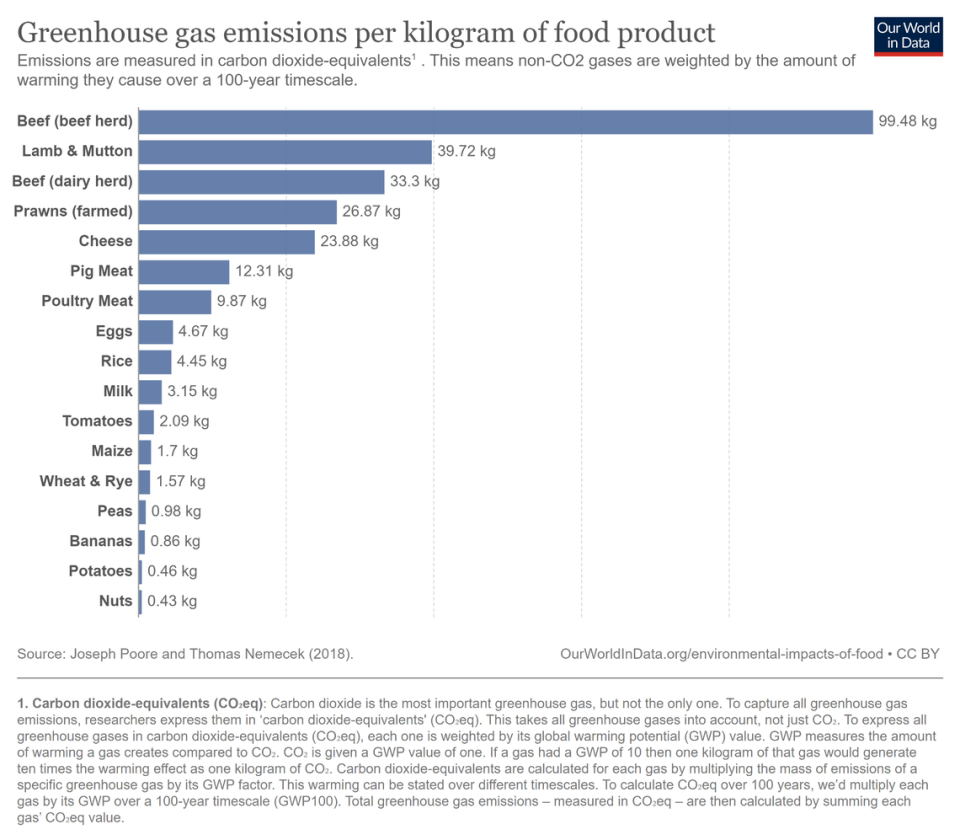

Eating plants is not only healthier for you but also healthier for the planet. Consuming meat, especially beef, lamb, or pigs consequently cause tons of greenhouse gasses (a key ingredient to human-caused climate change) to be released into the atmosphere. This occurs via raising the livestock as they emit methane during their digestion. Additionally changes to the land from herds of cattle, or other ruminant animals cause an increase in CO2 emissions.

Climate action and solution hub, Drawdown Georgia researchers found a 25% reduction in state-wide meat consumption (that is skipping meat for about two days a week) could reduce one megaton of CO2e. That is the same as removing 222,530 vehicles from the road that drive for one year.

Climate scientists make it abundantly clear that curbing CO2 emissions is one of the best ways we can stop our planetary warming.