Columbus State Community College is creating a pipeline to Intel. Here's how.

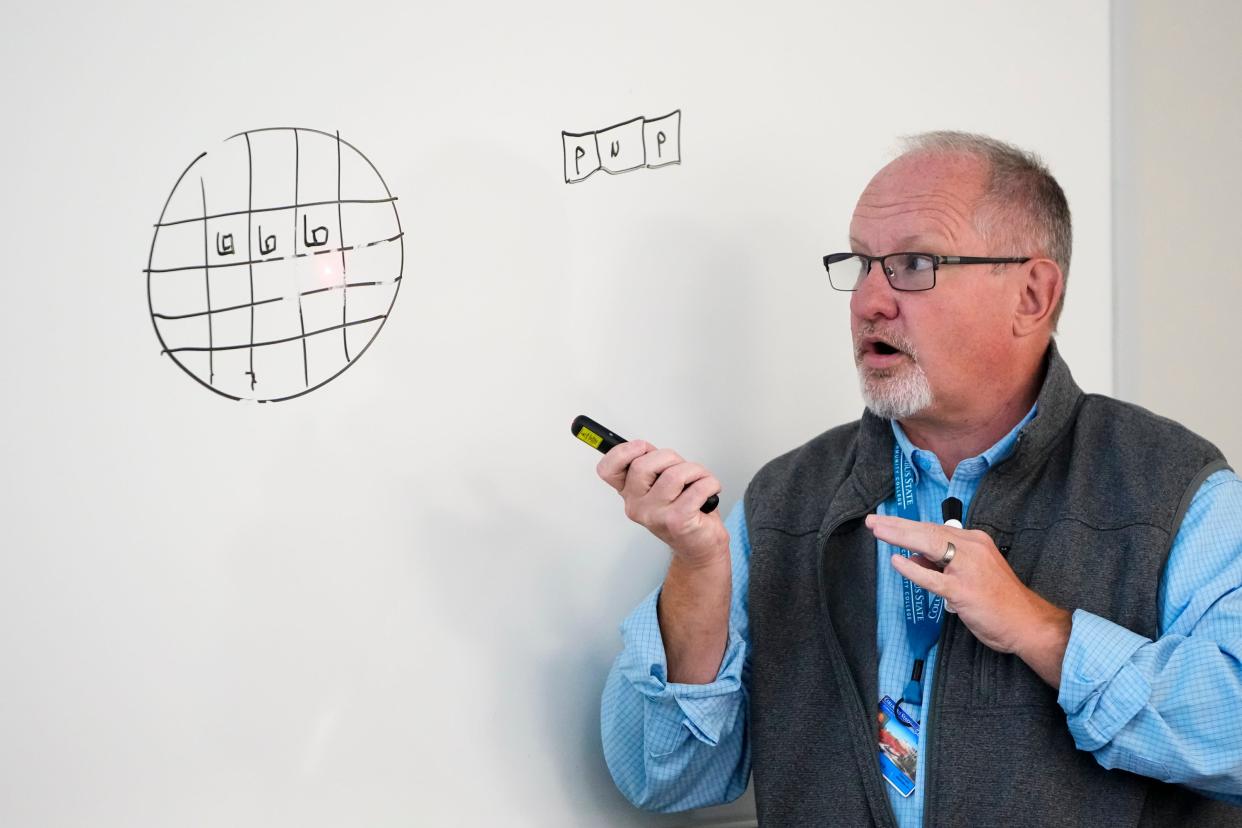

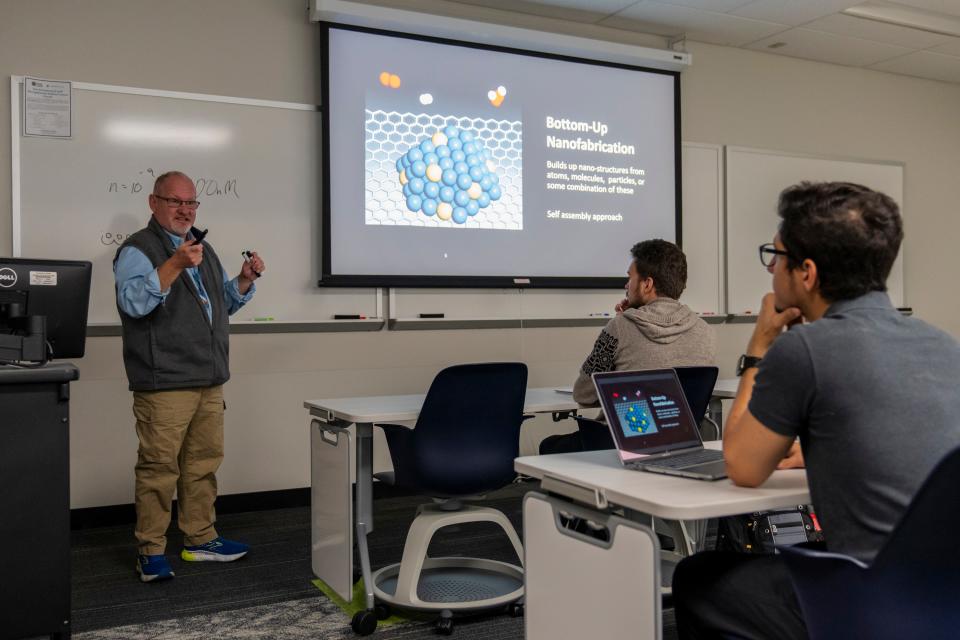

Chris Dennis clicked through his PowerPoint slides to a promotional video and pressed play. Clips of gas distribution systems flicked on the screen.

Dennis, an associate professor of supply chain management at Columbus State Community College, wasn't trying to sell his class on anything. Rather, he wants them to be prepared.

"Swagelock makes a lot of equipment for Intel," Dennis said, taking another swig from a bottle of Mountain Dew. "These are some of the different controls you'll see on the line."

Dennis is one of several professors teaching the first official cohort of Columbus State students who hope to land jobs at Intel's $20-billion microchip manufacturing plants in Licking County.

A two-year associate degree might not be the first thing that comes to mind when you think about a career in semiconductor engineering. Columbus State is trying to change that.

While many of Intel's engineering jobs require a bachelor's degree or higher, at least 70% of workers at its future Licking County-based fabs will be technicians, a role that only requires an associate degree. That means Columbus State and Ohio's nearly two dozen other community and technical colleges are working overtime to build the pipeline Intel needs to fill thousands of jobs.

"Intel puts a high value on technician roles and technician-level education," said Columbus State Community College President David Harrison.

Many of Intel's leaders started out at community colleges, Harrison said. People like Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger, who earned an associate degree from Lincoln Technical Institute in New Jersey before going on to Santa Clara University and later, Stanford University. It's one of the reasons that Columbus State was an early stakeholder in talks to recruit Intel to Ohio.

"We want to make sure people in Columbus can follow that same career path," Harrison said.

Intel investment used to create new community college curriculum

It's been a year since Intel announced it would invest $17.7 million over three years to fund eight projects involving more than 80 Ohio colleges and universities to develop semiconductor education and workforce programs.

One of those projects was the Ohio Semiconductor Collaboration Network. Intel awarded $2.8 million to a group of 23 community and technical colleges, led by Columbus State, to build and sustain a technician pipeline in the state by adding semiconductor-specific courses and equipment to existing advanced manufacturing programs.

Some of that funding was used by the Ohio Association of Community Colleges to develop courses for these degree programs. Courses are specific to the semiconductor industry, and include “Intro to Vacuum Systems” and “Semiconductor 101.”

Some of the updated programs being offered are micro-credentials, one-year certificates to become an entry-level technician, an associate degree route to become a mid-level technician, and a bachelor’s of applied science for becoming a process or quality engineer.

“Community colleges are at the forefront of the push for new technical certificates and degrees needed to provide the semiconductor sector with workplace-ready employees,” said Jack Hershey, president and CEO of the Ohio Association of Community Colleges, said at an event in August launching the curriculum. “We’re proud to have met the challenge in such a short period of time to create the educational content for workers for Intel hiring to begin.”

Some of this work was also recognized in a report from the Brookings Institution published earlier this year about how prepared central Ohio is for Intel's arrival. The report lauded Columbus State's collaborative "dual approach", working with other community colleges and local workforce boards to recruit and train students.

"First is a short-term certificate program for upskilling existing workers; second is a curriculum-enhancement approach to widen job prospects in the long term," the report said.

The goal of certificates is to encourage individuals "already working in adjacent advanced manufacturing fields to pursue a one-year certificate that is stackable and transferable," according to Brookings.

Then, as Intel arrives and grows, Columbus State plans to enhance its engineering technology degree and certificate programs with more skills and training.

"Based on skills competency mapping, 80% of these program’s curricula already aligns with what Intel’s jobs require; the focus now is on enhancing the remaining 20% with new subject matter," the report said.

“Intel is the catalyst for this effort," the report added, "but Ohio has long needed such an investment in statewide advanced manufacturing talent development strategies."

Intel careers drawing some students back to the classroom

Columbus State already had a foundation of engineering technologies programs. Many of its graduates moved onto careers at companies like Honda. Intel's presence has only seen that grow, Harrison said.

Enrollment in Columbus State's electro-mechanical engineering technology program is up 13% since last year, with 137 pursuing certificates and degrees, according to college data. All of the college's engineering, manufacturing and engineering technology programs have increased enrollment about 15% year over year.

"With a technician-level skill set, a bachelor's degree is not required. Student debt is not required," Harrison said. "Right now, it's about helping people understand these opportunities."

Harrison said having a program with clear outcomes is one way Columbus State is working to educate future students and their families.

That was the case for Bennett Waldo.

Waldo, 23, of Westgate, had attended the University of Cincinnati Blue Ash College until the pandemic moved everything online. Undecided about his major and less than thrilled about online learning, he stopped and started working as a bartender.

After Intel announced it was coming to central Ohio, Waldo's brother started doing some research. "Could this be something you're interested in?" he asked. Waldo thought so.

Now, Waldo is studying electro-mechanical engineering technology. He hopes to graduate in a couple of years and start working for Intel.

"It feels like I'm one of those people who invested in Facebook early and struck while the iron was hot," he said.

Being on the "ground floor" of Columbus State's program, Waldo said, is an exciting prospect.

Dennis, his professor, agrees.

Dennis grew up in "the Honda era," and remembers seeing how a single company moving into an area changed the entire economy. With years of experience in the semiconductor industry, he said he's anticipating the same with Intel.

"This is going to change central Ohio forever," Dennis said.

Sheridan Hendrix is a higher education reporter for The Columbus Dispatch. Sign up for Extra Credit, her education newsletter, here.

shendrix@dispatch.com

@sheridan120

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: A look inside Columbus State's community college-to-Intel pipeline