Columbus’ water worries are over thanks to landmark Chattahoochee River deal with Alabama

When a mother in Atlanta draws a bath for her six-week-old son, or rapids splash a rafter’s face as he treks through Columbus, or anglers fish at Lake Seminole, they are all connected by the throughline of the 450-mile Chattahoochee River.

For the last 33 years, sharing this vast resource equally and fairly throughout the Southeast, especially in times of drought, has confounded state leaders and the Army Corps of Engineers. (ACOE). And until now, decisions of allocation have only been settled through lawsuits.

But last week, a proposed agreement between Gov. Ivey of Alabama, Gov. Kemp of Georgia, and the ACOE marked a new era in the Apalachicola-\Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) “water wars” saga.

The proposal is centered around fair distribution to simultaneously meet health and environmental standards and needs of business, energy, and recreation during times of drought. Water throughout the Chattahoochee basin is measured by flow rates and elevations of reservoirs.

“The agreement gives us something we’ve never had before: a guaranteed minimum flow,” Vic Burchfield, VP of Columbus Water Works said. “Columbus Water Works has been advocating for 1,350 CFS for years as a minimum average daily flow in the middle stretch of the Chattahoochee.” (River water flow is measured by cubic feet per second (CFS). A flow of 1,000 CFS is the equivalent of 4,000 basketballs flowing all at once.)

Minimum flow means water providers and wastewater utilities (which Columbus Water Works operates both in Columbus at Fort Moore) can consistently provide drinking water and discharge wastewater.

“Minimum flow is good for a river and community because it is good for water resource needs and recreational needs,” Burchfield said. “During drought, the minimum flow is really critical.”

The flow in Columbus is a direct result of the North Highlands Dam flow schedule and hydropower intake, which is operated by Georgia Power and monitored by the ACOE.

Georgia Power did not respond to comment when asked whether this new agreement would affect their flow schedule to meet their capacity of 65 megawatts (MW) of hydroelectric power output. 65 MW can power about 40,000 homes for a day.

“This is the first time the dam would have to control releases so that the minimum flow is maintained,” Burchfield said. “ Now they have to input into their calculations the minimum flow requirements.”

Daniell Gilbert of White Water Express said white water trips have still been active in flows as low as 800-900 CFS. White water rafting trips have been an economic engine in Columbus for the past 10 years, as recently reported.

Columbus Water Works pulls drinking water above where the new minimum flow is required, but discharges wastewater from the treatment plant south of the city. The discharge has to flow 1,150 CFS, Burchfield said, per their wastewater (NPDES) permit.

“This proposal is more favorable for wastewater utilities that discharge into streams,” Burchfield said.

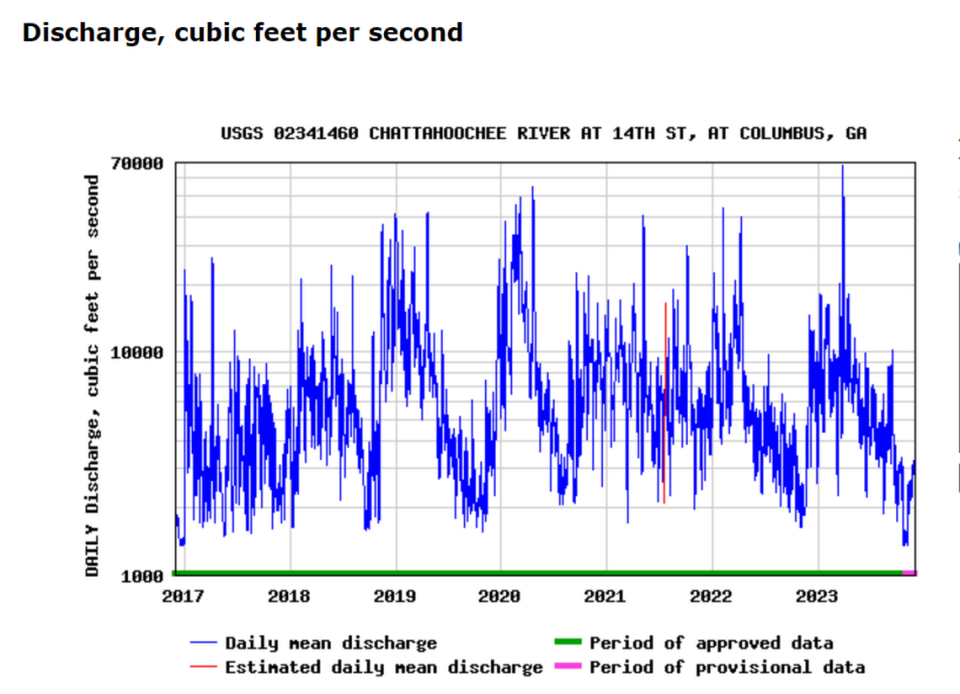

At the 14th Street Bridge, a gauge monitor from the US Geological Survey (USGS) constantly measures the CFS in Columbus.

The proposal says the minimum flow rate in the Columbus stretch of the Chattahoochee must be 1,350 CFS on a rolling seven-day average. When there is a drought (for particular drought zones) it only needs to meet that flow two days per week.

The flow rates at the 14th Street Bridge have been as high as 7,000 CFS and as low as 1,200 CFS in the last six years, according to the USGS data. In November they ranged from 1,370 to 3,087 CFS.

The variation in CFS in Columbus is due to a variety of factors including the release schedule of dams in West Point, rain, floods, and drought. Climate change exacerbates droughts, making them more frequent, longer, and more severe.

The Not-So-Visible Drought

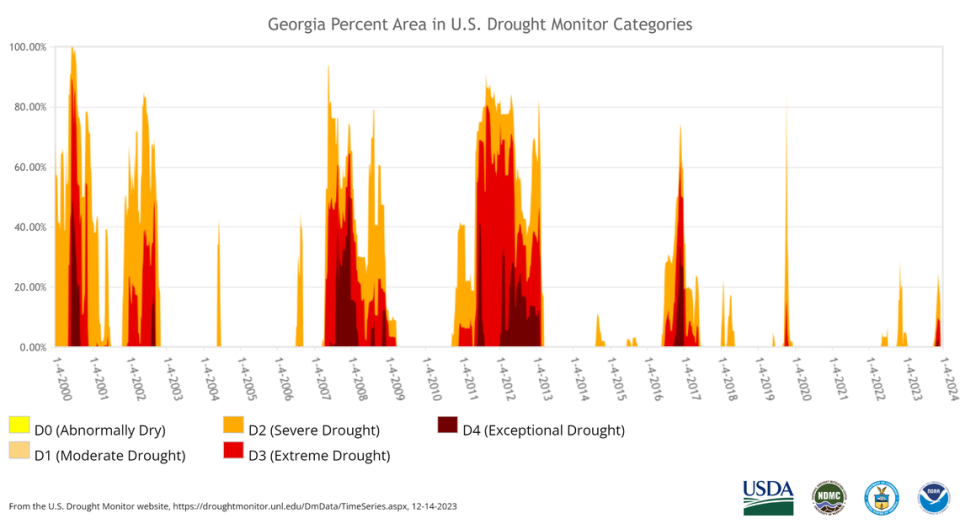

Georgia has had several droughts in the past twenty years.

In 2012 and 2016 droughts lasted from six to 10 months,” Lee Ellenburg, drought researcher of the University of Alabama said. “The water wars got hot and heavy in 2007 during a major multi-year drought.”

As of November parts of Georgia entered an extreme drought.

Georgia’s plentiful reservoirs create an illusion that there isn’t a drought.

“Drought’s aren’t noticeable in Georgia,” Tod Hamill, a hydrologist with Southeast River Forecast Center said. “All of the reservoirs in Georgia are man-made [because of the dams]. If we didn’t have those reservoirs our droughts and floods would be more pronounced. The reservoirs benefit the systems from top (Atlanta) to bottom (Lake Seminole).”

Hamill suggests the last 20 years the region’s leadership hasn’t been on the same page.

“There were deficiencies in how to share the water.” He continued, “deciding the best way to keep water up north for Atlanta drinking water and how much to let out. I don’t think there has been enough studies during a serious drought to manage these decisions. Now they are going to do a study to see if this is all feasible.”

The proposed agreement requires the ACOE to conduct an environmental review as well as take into consideration public comments for the next 12 months.

“We need to be cognizant of how to think about these minimum flows in the context of climate change,” Chris Manganiello, policy director of the Chattahoochee Riverkeepers said. “The first water manual was made in 1958, then revised in 2017. It’s not clear that climate change was taken seriously when it was revised. Now, we have the opportunity to think about that during this review process and evaluate the conditions we’ve witnessed over the last 10 years for what the future might look like.”

What’s Alabama’s Stake?

Manganiello is “cautiously optimistic because this resolves the tri-state water wars outside of a courtroom, which is was [Riverkeepers] have always advocated for”.

Though Alabama doesn’t have a large population that relies on the Chattahoochee, the same way Atlanta metro does (the 21-county metro Atlanta area grew by 3.1 million people from 1990 to 2020), the state relies on the Chattahoochee for irrigation and energy, according to experts.

The Farley Nuclear Plant in Columbia, Alabama produces 1,800 MW of electricity (19% of Alabama Power’s electricity) and is powered by pressurized water reactors, which it draws from the Chattahoochee.

Southern Company declined to respond when asked how much water Farley Nuclear pulls from the Chattahoochee to power the plant.

The agreement proposes the Columbia stretch of the Chattahoochee must have a minimum flow of 2,000 CFS, and Lake Seminole, must maintain an elevation of 76 feet. Columbia’s CFS has remained near that range for the last decade, according to USGS data.

If this proposal passes, Alabama will drop its 2017 Master Manual lawsuit against the ACOE with claims that Atlanta’s water supply needs that the ACOE managed were unlawful. Alabama appealed the court’s judgment to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, according to the Atlanta Regional Commission. For now, the Eleventh Circuit court challenge is paused.

“This agreement is a win-win for our states, with neither side sacrificing what is important to them,” Gov. Brian Kemp said in a press release last week. Governor Ivey of Alabama agreed that it is a win-win solution.

Columbus Water Works and Chattahoochee River Keeper both look forward to the public comment period and the environmental review.

“People should care,” Manganiello said. “Any stakeholder involved in the ACF river basin should be involved in this process.”